Article: The Albemarle Report, 1960

A story of its full transcription 60 years later

The Albemarle Report, 1960

A story of its full transcription 60 years later – Adam Muirhead

It started in 2018 with a question on my blog;

‘Where did the 4 Cornerstones of Youth Work come from’?

Not the Albemarle Report is the answer. However, this was the first suggestion I had back at the time from someone who seemed fairly sure; I decided I needed to investigate. My probing started with a Google search for ‘the Albemarle Report’, hoping to find a copy. No Report. What you will find is a really helpful overview by Smith and Doyle (2002) and some of the report chapters, on the infed site, and even some of the related debate in Parliament from 1960 (transcribed) – but what of the thing itself? I asked around and was kindly sent a roughly scanned copy by an ally. Aha! I could finally get a feel for the thing from this, but as a scan, there was no way to quickly search within the document for key words or anything. Reading all 136 pages would be slow – how much would it cost to get the whole thing transcribed by a company?? $248.60 + VAT as it turns out. Not a hideous cost but it was never going to be the way I’d choose to spend that cash, besides, outsourcing cheaply like this meant it wasn’t going to be spell-checked, formatted and the returned document was likely be a monstrous mess. So, I resolved to do it myself.

Even with OneNote 2016’s Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software, this was a big job and the poor quality of my scanned copy meant that errors were too regular; small printing smudges would add untold grammatical mess whilst blotchy characters meant every 5th word wanted its spelling corrected. What I needed was an original copy of the report and a half-decent scanner. As it turns out, even with those things there is a lot of formatting, corrections, adding in whole sentences that it skips for no reason… Tables were all to be constructed from scratch and their data inputted painstakingly line by line. So, was it worth it?

Yes!

I’ve gained my own massive insight into this report and it is fascinating! Here are some of my personal highlights:

- It gives an incredible picture as to the state of the sector at the end of the 1950’s. I’d agree that this Report was a watershed for our profession, but it’s true that an amazing amount of work had already been happening, and if it hadn’t been for the principles of practice already being there, the Albemarle Report would not have had the solid foundation on which to base its findings and recommendations.

- Yes, it references delinquency (12 times – which took me all of 5 seconds to discover) as a rationale for the enhancement of the Youth Service. Certainly, parts are couched within a deficit paradigm. But in other ways, its ethical approach is on the money; It speaks very clearly to youth participation, equal rights of access for boys and girls and does actually try to dismiss popular public rhetoric about how ‘bad’ the adolescents of the day actually are.

- Whilst Bernard Davies’ comments in his 1999 account of the Albemarle Report are right in suggesting that the focus of the practice proposed was based on a desire for individual outcomes, the Report more broadly acknowledged society’s responsibility to respond and support young people. It also recognised the social/contextual factors at play, like “the constant threat of nuclear catastrophe” on p29. This distinguishes the Report’s approach from some of today’s social policy discourse, which can seemingly suggest that one’s own bootstraps is all that are needed to overcome adversity, whatever the societal context.

- It uses poetry on a few occasions to make its point. See Burns’ work on p31, W.H. Auden on p39 and a reference to ‘Lines to a Don’ by Hilaire Belloc on p48. There’s lots of character woven into the writing!

- We use the ‘voluntary principle’ these days to describe the way young people choose to take part in activities. The Report actually uses the ‘voluntary principle’ to describe the need and desire for more volunteers to staff/support the delivery. Just interesting how this term was important then and also now, but for different reasons.

- The emphasis on the power and value of pure ‘associational’ youth work is inspiring. For instance, on p52 it states “To encourage young people to come together into groups of their own choosing is the fundamental task of the Service. Their social needs must be met before their needs for training and formal instruction”. The term ‘Associational Youth Work’ is one I wish was used more now, over ‘Open Access’ or ‘Universal’.

- It recognises the necessary adaptability and flexibility of services in a way that we would describe as ‘youth-led’. On p55 it states that “there is a kind of footloose group that deliberately prefers the odd, the heterodox rendezvous to the most civilised amenities”, and that Youth Work should be open to meeting their needs too. ‘Heterodox Rendezvous’ will be the name of the next Detached Youth Work bid I write.

- In spite of what one commentator (Jeffs, 1979) described as an “ill-prepared” approach to the report’s writing, based on the Albemarle Committee’s desire to work quickly, I found the level of research with stakeholders to inform the report was impressive. All of the witnesses who submitted are listed in Appendix 1, followed up by great long tables of information from them and local education authorities on things like the number of youth centres there were, how many full-time/part-time workers were employed at the time, through to things like expenditure on training.

- One youth leader who gave evidence to the Albemarle Committee was describing our role in taking the strain of adolescent exuberance from families and suggested we were like “lightning conductors” (p106). It’s not a term I’ve heard used for us since, but I really like the unintended imagery it conjured that was less like a copper rod beside a building, and more like someone trying to lead a chaotic and energetic orchestra!

My hope for this transcription is that it proves interesting and useful for others too, perhaps inspiring an even wider love for the history of Youth Work.

…Oh, and the ‘4 Cornerstones’ are born of the Ministerial Conferences in the 90’s, it seems…

For comments, mockery or suggested amendments, find me on Twitter @youthworkable.

A few things to note about how the Albemarle report is availible on Youth and Policy:

- The text below is a full transcript of the 1960 report in HTML, so it’s fully searchable (ctrl+F) and clicking on the table of contents will take you to that section.

- The tables do not always format properly and the one in appendix 4 is massive! All the tables in the appendices are available in Excel and Open Spreadsheet format. If you want play around with the data, you might want to adjust for inflation. So, funding amounts should be multipled by 235.39 for a 2019 comparison.

- You can download Adam’s beautifully presented transcript, with accurate page numbers, Royal Coat of Arms cover page, and monospaced typewriter-like font throughout as a PDF.

- For convenience we have provided the transcript in Word and Open Document format.

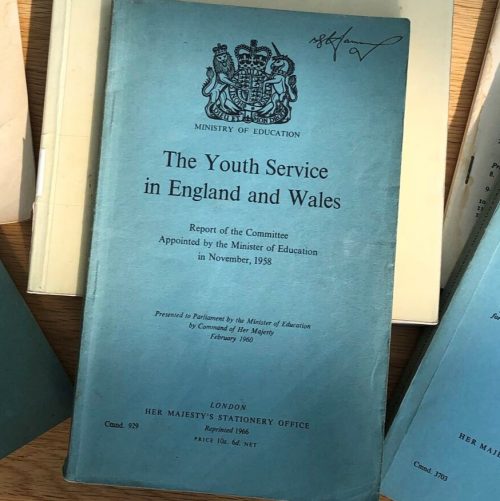

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION

The Youth Service in England and Wales

Report of the Committee

Appointed by the Minister of Education

in November, 1958

Presented to Parliament by the Minister of Education

by Command of Her Majesty

February 1960

LONDON

HER MAJESTY’S STATIONARY OFFICE

SIX SHILLINGS NET

Cmnd. 929

NOTE: The estimated cost of preparing and publishing this Report is £2,225 9s. 1d., of which £1,259 0s. 0d. represents the estimated cost of printing and publication.

MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE

The Countess of Albemarle, D.B.E. (Chairman)

RL Hon. D. F. Vosper. T.D., M.P.

Mr. M. J. S. Clapham

Mr. R. Hoggart

Mr. D. H. Howell

Mr. R. A. Jackson

Miss A. P. Jephcott

Mr. J. Marsh

Mr. L. Paul

Reverend E.A. Shipman

Professor A. G. Watkins

Dr. J. W. Welch

Councillor Mrs. E. M. Wormald, J.P.

Secretary: Mr. E. J. Sidebottom, H.M.I

Assistant Secretary: Mr. E. B. Granshaw

Chapter 1: The Youth Service Yesterday and Today

CHAPTER 2: Young People Today Part I: THE CHANGING SCENE

- THE BULGE

- THE ENDING OF NATIONAL SERVICE

- PHYSIQUE

- CHANGING PATTERN OF WOMEN’S LIVES

- DELINQUENCY

- HOUSING

- EDUCATION

- MONEY TO SPEND

- EMPLOYMENT

- LIFE AT WORK

CHAPTER 2: Young People Today PART II: THE WORLD OF YOUNG PEOPLE

CHAPTER 3: Justification and Aims of the Youth Service

CHAPTER 4: The Youth Service Tomorrow

- STATUTORY PROVISION FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE YOUTH SERVICE

- THE TASK OF THE MINISTRY

- THE TASK OF THE LOCAL EDUCATION AUTHORITIES

- THE TASK OF THE VOLUNTARY YOUTH ORGANISATIONS

- THE VOLUNTARY PRINCIPLE

- THE TASK OF THE FOURTH PARTNER

- INSPECTION AND CO-ORDINATION

CHAPTER 5: Activities and Facilities

- I. ACTIVITIES

- 1. ASSOCIATION

- 2. TRAINING

- 3. CHALLENGE

- II. FACILITIES

- 1. PREMISES AND EQUIPMENT

- 2. PROVISION FOR PHYSICAL RECREATION

CHAPTER 6: Staffing and Training

- PROFESSIONAL YOUTH LEADERS

- l. WHY FULL-TIME LEADERS?

- 2. THE LONG TERM SCHEME

- (i) Recruitment and training

- Content of training

- (iii) Schemes of training undertaken by voluntary organisations

- (iv) Grants

- 3. THE EMERGENCY SCHEME

- (i) Recruitment and training

- (ii) The content of training

- 4. QUALIFICATION

- 5. SCALES OF SALARIES

- PART-TIME LEADERS (PAID AND VOLUNTARY)

- INSTRUCTORS AND HELPERS

- ORGANISERS

- GRANTS FROM THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION

- (a) SOCIAL AND PHYSICAL TRAINING GRANT REGULATIONS, 1939

- (b) PHYSICAL TRAINING AND RECREATION ACT, 1937

- EXPENDITURE BY LOCAL EDUCATION AUTHORITIES

- EXPENDITURE BY OTHER LOCAL AUTHORITIES

- CONTRIBUTIONS FROM VOLUNTARY SOURCES

- CONTRIBUTIONS FROM YOUNG PEOPLE

CHAPTER 8: The Position in Wales

CHAPTER 9: The Youth Service and Society – A New Focus

CHAPTER 10: Recommendations and Priorities

- THE YOUTH SERVICE TOMORROW (CHAPTER 4)

- ACTIVITIES AND FACILITIES (CHAPTER 5)

- STAFFING AND TRAINING (CHAPTER 6)

- FINANCE (CHAPTER 7)

- THE YOUTH SERVICE AND SOCIETY (CHAPTER 9)

- PRIORITIES

- APPENDIX 1 – List of bodies who submitted written evidence to the Committee

- APPENDIX 2 – Grants offered under the Social and Physical Training Grant Regulation, 1939, to national voluntary youth organisations

- APPENDIX 3 – Total grants from the Ministry under the Social and Physical Training Grant Regulations, 1939

- APPENDIX 4 – Statistical information supplied by local education authorities in England and Wales for the financial year 1957-58

- APPENDIX 5 – Expenditure by local education authorities on recreation and social and physical training

- APPENDIX 6 – Estimated populations

- APPENDIX 7 – Estimated number on roll 15-18+ in maintained and assisted primary and secondary schools

- APPENDIX 8 – Details of the Government’s plans for ending national service

- APPENDIX 9 – Rates (per 100,000 of the related population) for males and females aged 8 – 20 years found guilty of indictable offences in the years 1938 and 1946 – 1958

- APPENDIX 10 – Estimated numbers of full-time leaders required

- APPENDIX 11 – A suggested syllabus for a one-year full-time emergency training course

Introduction

1. The Committee was appointed by the Minister of Education in November, 1958. We were given the following terms of reference: “To review the contribution which the Youth Service of England and Wales can make in assisting young people to play their part in the life of the community, in the light of changing social and industrial conditions and of current trends in other branches of the education service; and to advise according to what priorities best value can be obtained for the money spent.”

2. We were appointed at a most crucial time. First, because several aspects of national life, to which the Youth Service is particularly relevant, are today causing widespread and acute concern. These include serious short-term problems, such as that of the ‘bulge’ in the adolescent population. They include also much more complex and continuous elements of social change, elements to which adolescents are responding sharply and often in ways which adults find puzzling or shocking. Secondly, because it soon became clear to us that the Youth Service itself is in a critical condition. We have struck by the unanimity of evidence from witnesses (and their views out by our own observations) on these points:

(i) that the Youth Service is at present in a state of acute depression. All over the country and in every part or the Service there are devoted workers. And in some areas the inspiration of exceptional individuals or organisations, or the encouragement of local education authorities, have kept spirits unusually high. But in general we believe it true to say that those who work in the Service feel themselves neglected and held in small regard, both in educational circles and by public opinion generally. We have been told time and time again that the Youth Service is ‘dying on its feet’ or ‘out on a limb’. Indeed, it has more than once been suggested to us that the appointment of our own Committee was either ‘a piece of whitewashing’ or an attempt to find grounds for ‘killing’ the Service. These are distressing observations, but we feel they have to be recorded since they indicate accurately the background of feeling among many of those engaged in the Service; they should therefore be fully appreciated at the very of our Report. No Service can do its best work in such an atmosphere;

(ii) that our witnesses were nevertheless in no way disheartened about the fundamental value of the Service. They gave us the firm impression (and again this was supported by our own observations) that a properly nourished Youth Service is profoundly worthwhile; and that it is of special importance in a society subject to the kinds of change which we have noted above and which we shall describe later.

3. We have therefore been meeting in conditions of quite unusual urgency and with a sense of working against time. As a result we have not undertaken any large-scale research projects what is a very wide field. These can be carried out once the main justification and aims of the Service have been established. Many enquiries have indeed already been made, but have so far produced little positive action. Again, we hope that our statement of principles and policy will allow these earlier enquiries, and some which are going on at present, to be enlisted in the improvement of a revivified Youth Service.

4. In short, we have thought of ourselves as a charting committee and have tried, as urgently as is compatible with thoroughness and comprehensiveness, to tackle the essential questions: to establish the place of the Youth Service in the larger social and educational scene; to chart a desirable course; and to outline those measures (for both the short and the long-term) which will best give the whole Service the new heart it so badly needs.

5. The chapters which follow fall into main groups.

First, after surveying the history, present scope and limitations of the Service (Chapter 1), we review the changing and try to assess the impact on young people of these changes (Chapter 2). We then set out to re-establish the social and individual justification for the Youth Service. Chapter 2, Part II and Chapter 3 contain our fundamental thinking on needs, aims and principles.

Second, we have sought to build upon this foundation the framework for a Youth Service which will be adequate to the needs of young people. We therefore formulate the tasks of the various partners in the Service (Chapter 4), and suggest the opportunities, activities and facilities which need to be provided (Chapter 5).

Third, we examine and emphasise the responsibilities which flow from our re-phrasing of the scope of the Youth Service, and make our specific recommendations (Chapters 6—10).

6. It will be quickly seen that we believe a considerable expansion is needed in the provision made for the Youth Service. No less will do since, at a time when it should have been receiving exceptional encouragement, the Service has been allowed slowly to lose confidence. Two kinds of measure are therefore needed:

(i) blood-transfusions: that is, short-term measures to meet immediate needs (e.g. the problem of the “bulge”). These may require emergency expenditure.

(ii) measures for sustained and continuous nourishment.

7. We propose provision for planned development over two five-year periods under the surveillance of a Development Council. The main emphasis in the first five years would be on (i). We believe all these measures are necessary and urgent. But it is important not to encourage excessive hopes. The “problems of youth” are deeply rooted in the soil of a disturbed modern world. To expect even the best Youth Service to solve these problems would be to regard it as some sort of hastily applied medicament.

8. As we seek to show later, the Youth Service is deeply relevant to the needs and complexities of a modern society enjoying a rising standard of living. But its real achievements are bound to be sometimes difficult to measure statistically, and may only be seen clearly over a long period. This is yet another reason for losing no time in making a proper start.

9. the course of our work, we have considered written evidence from 69 bodies and have heard oral evidence from 20 of these (Appendix l). In addition, a large number of suggestions, sometimes in the form of memoranda, have been received. We have interviewed several individual people with a free-lance interest in or special knowledge of youth work, and we have consulted many others informally. We have received statistical information from Government departments and, in reply to a questionnaire of our own, from all 146 local education authorities in England and Wales. The Central Advisory Council for Education (England) has made available to us the results of a survey carried out in 1957[1]; a section of this survey dealt with the leisure-time interests of young people after leaving school and was based on questions put to a sample of those who had attended maintained schools. We have kept in touch with the Council and with two other bodies which were examining social problems affecting young people — the Ministry of Health’s Working Party on Social Workers in the Local Authority Health and Welfare Services, and the Industrial Training Council which was set up after the publication of the Carr Committee’s Report[2] in 1958. We have read reports on the Youth Service written by H.M. Inspectors of Schools, and have received several publications giving information about youth work abroad, particularly in Europe. We are grateful to all those who have helped us in these ways. Individual members of the Committee have visited youth groups at work in various parts of the country; several members were able, during visits abroad for other purposes, to learn something about youth work in the United States of America and four other countries.

10. We have met on 30 days, of which two were in Cardiff and three constituted a residential week-end conference.

Chapter 1: The Youth Service Yesterday and Today

HISTORY

11. In 1939 the Board of Education called the Youth Service into being with the issue of a single circular. This could not have happened but for what had gone before. The voluntary organisations had been labouring in the cause of youth, some of them for well over half-a-century. Some of the local education authorities had been trying to help and co-ordinate the voluntary work in their areas through juvenile organisations committees. And in the 1930s the State itself had tried to promote social and physical training and recreation. What the Board did at the start Of the war was to bring these three parties, State, education authority and voluntary organisation, into a working arrangement to which the term “Youth Service” has ever since been given.

12. Circular 1486 the Board undertook “a direct responsibility for youth welfare”. The President had set up a National Youth Committee, and local education authorities were called on to set up youth committees of their own. Key phrases in the circular were: “close association of local education authorities and voluntary bodies in full partnership in a common enterprise” . . . “ordered scheme of local provision” . . . “indicate the lines on which a real advance can be made under more favourable conditions” . . . “new constructive outlets”. Later circulars made it clear that the Board regarded the Youth Service as a permanent part of education. So did the White Paper on Educational Reconstruction (1943), which gave a separate section to the Youth Service. The McNair Report (1944) encouraged the public to think of youth leadership as a profession, which ought to have proper conditions of training and service. The Youth Advisory Council (the successor to the National Youth Committee) produced two reports (1943 and 1945) which were full of hope for the future of the Service. Finally ‘the Education Act, 1944, not only made it a duty on authorities to do what they were already doing out of good-will, but offered in addition the county college, a mighty ally to the Youth Service.

13. With the sense that the Youth Service was here to stay, authorities and voluntary bodies responded vigorously. In spite of natural early difficulties of adjustment a creditable measure of co-operation was achieved. The Youth Service was much written about, and youth workers of the time speak of the interest and enthusiasm of the public. Universities and university colleges offered training courses for professional leaders, and as the war ended the Service seemed full of promise.

14. In 1945 the Ministry of Education made it plain that they did not intend for the present to put into effect the McNair recommendations about youth leaders. All the same the outlook still seemed bright enough to attract numbers of able men and women leaving the armed forces into the courses for professional leaders offered by universities and voluntary organisations. For two or three years longer the Service made some progress. It continued to be widely discussed, and four of the Ministry’s pamphlets published between 1945 and 1949 took it into serious account. Then the wind began to blow cold. With one economic crisis after another the Ministry could do no more than indicate that the Youth Service (with other forms of “learning for leisure”) must be held back to allow, first, for the drive for new school places and, later, for the development of technical education. The county college looked as far off as ever. The Jackson Committee (1949)[3] and the Fletcher Committee (1951)[4] produced reports on the training and conditions of service of professional youth leaders. Neither was put into effect. The flow of recruits shrank, the number of full-time leaders fell away and the university and other full-time courses closed down one by one until today only three survive[5] With the Ministry unable to give the signal for advance certain authorities lost heart. Public interest flagged too, and not surprisingly voluntary bodies felt the effect. It is easy to over-expose the picture and to fail to do justice to the good and valiant work which has been done since the war and is still being done. All the same the Youth Service has not been given the treatment it hoped for and thought it deserved, and has suffered in morale and public esteem in consequence.

PRESENT MACHINERY

15. The Service that emerges from this history is not one homogeneous organisation but a partnership of a complicated kind. Of the three parties to the partnership the Minister has the particular duty of making plain the national policy within the general terms of which the Service is to work. This he can do through official circulars or public pronouncements. His decision on priorities is important: no less is the influence he can have on public opinion, on the community’s awareness of priorities and needs and its response to them.

16. There is now no national council or committee through which the Ministry can discuss national policy for the Youth Service with the local authority associations and national voluntary organisations together. The Minister can, however, refer questions to the Central Advisory Councils for Education, and these can and have included matters touching on the Youth Service. Questions of common policy are discussed from time to time between the Ministry and representatives of the Standing Conference of National Voluntary Youth Organisations or individual organisations. The Ministry are represented by an observer on the Standing Conference, and certain of H.M. Inspectors keep in touch with the headquarters of organisations and may sit as assessors or observers on some of their committees.

17. Direct help to the Service from the Ministry takes the form of grants offered under the Social and Physical Training Grant Regulations, 1939.[6] These grants are given in aid of the administrative and training work of national voluntary youth organisations, towards the expenses of training full-time leaders and towards the cost of premises and equipment for youth clubs provided by voluntary bodies.

18. The Ministry also give indirect help through the grants offered under the Physical Training and Recreation Act, 1937 to national voluntary organisations which provide services (especially coaching in physical pursuits) for young people as well as adults. Capital grants are offered under the same Act for local projects meant primarily to benefit adults; these include playing-fields, swimming-baths, community centres and village halls. Young people too can benefit from these forms of provision.

19. If we turn to relations between the Ministry and local education authorities, it is clear that grant-aid now matters much less than it did, since the Youth Service has ceased to be aided by a percentage grant. Control of capital investment still remains; the Minister regulates the amount and type of building by requiring authorities to submit for his approval their major building programmes and certain minor projects. Nevertheless since April, 1959, the authorities have been freer than they were to undertake minor building works if they want to. The Ministry are represented locally by H.M. Inspector whose job is to keep in touch with authorities, local associations and the work in the field. Much of his most useful work is the advice and encouragement he gives in informal visits to clubs and other units. From time to time he reports to the Minister on the quality of the authority’s service or on particular groups.

20. The local education authority are responsible for making the partnership work. They have to interpret national policy in terms of local needs; to set up the machinery through which the authority and voluntary bodies can work together; to help and to service local groups; and in certain conditions to provide clubs and centres themselves. Help and servicing may include grants of money, advice and information from the authority’s organisers, training courses, the provision of instructors, the loan of equipment, premises, playing-fields and camp sites, perhaps the organisation of a youth orchestra, a youth theatre, athletics centre, foreign visits and exchanges, and local festivals. The authorities’ duties are undertaken by a responsible committee, normally a youth committee. Many appoint further education organisers or Youth Service officers to carry out the field-work, committee-work and administration. We are very much alive to the value of the work of these officers and to the importance of their posts.

WHAT IT COSTS

21. We are primarily concerned with value for public money, but we think that as a beginning the extent to which the Youth Service is financed by voluntary contributions should be recognised. We have tried to find out how much comes from these voluntary sources, but three factors prevented our getting a complete picture. First, the finances are extraordinarily complex: money comes from members’ subscriptions, trusts, donations and special money-raising efforts; these contributions are made at all levels, national, county and unit; and there is little uniformity of practice among the many kinds of organisation. Second, it is impossible for some organisations to separate their expenditure on young people aged 15—20 from that on adults and children. Third, units in the field are usually autonomous, and they keep their own accounts which are not readily available.

22. The following examples from our evidence, however, show what proportion of income in the year 1957-58 is claimed by the bodies concerned to have come from these voluntary sources:

| National Association of Boys’ Clubs At headquarters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .In local associations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Affiliated clubs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Per cent.

75 88 78 |

| Young Women’s Christian Association At headquarters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

88 |

| National Association of Mixed Clubs and Girls’ Clubs At headquarters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

60 |

| Young Men’s Christian Association At headquarters (for young people under 21) . . . . . . .In local associations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

93

87 |

The evidence of the Standing Conference of National Voluntary Youth Organisations suggests that it is not at all unusual for its member organisations to have to raise from private and voluntary sources 90 per cent of their total yearly expenditure on headquarters administration, the provision of regional organisers and the training of leaders. What must, of course, be remembered about these several figures is that they are merely percentages of income or expenditure, which may in either case be quite inadequate to meet the needs of the organisations concerned.

23. We now turn to expenditure from public funds. Total direct expenditure on the Youth Service by the Ministry of Education under the Social and Physic-al Training Grant Regulations, 1939 was £317,771 in 1957-58.[7] This represents only a small part of Ministry expenditure on all forms of education, which amounted to £355,400,OOO[8] in that year.

24. When we came to examine the expenditure of local education authorities, under sections 41 and 53 Of the 1944 Education Act, the practice of including expenditure on adults and schoolchildren again made it difficult to assess accurately the amount spent on young people aged 15—20. We therefore sent a questionnaire to all authorities asking for details of expenditure in 1957—58 under the following headings:

(iii) clubs and centres maintained by the authority;

(iv) leaders employed by ‘the authority (full-time and part-time);

(v) youth organisers and youth officers employed by the authority;

(vi) grant aid to clubs and centres maintained by voluntary bodies;

(vii) grant aid to the county or local headquarters of voluntary organisations;

(viii) Youth Service training and aid to students;

(ix) other Youth Service expenditure

25. Their replies[9] show how varied and uneven the provision is. For example, expenditure on training including aid to students was £54,189, or a little over 2 per cent of total Youth service expenditure; yet some authorities appeared to spend nothing on this item. About £760,000 was spent on centres which the authorities themselves maintained, and rather less than £500,000 on aid voluntary youth clubs and units; again variations between the authorities are great even when allowance is made for differences of population. It must be remembered, however, that some authorities also provide services other than these for the benefit of the 15-20 group in the form of advice from their organisers and help from instructors. Total expenditure on the Youth service by local education authorities in 1957-58 was about £2½ million. This represents almost exactly 50 per cent of the expenditure shown under sections 41 and 53 of the Act for recreation generally.[10]

26. Thus in 1957-58 total direct expenditure on the Youth Service by Ministry and authorities combined was a little over 2¾ million. Of every pound they spent on education about 1d. went on the Youth Service.

27. We have examined the actual expenditure over the 12 years up to and including 1957-58 and we have also taken into account the fall in purchasing power of the pound.[11] In terms of real money, direct expenditure by the Ministry on the Youth Service has fallen by about a quarter over these years. We cannot easily calculate the extent to which the Youth Service expenditure of local education authorities has changed in these years, because of the imponderables mentioned above; but their total expenditure on recreation and social and physical training for adults, young people and school children appears to have increased substantially over the period: in terms of real money, by almost a half.

PRESENT AIMS

28. In Circular 1516 of 27th June, 1940, the Board of Education gave “some guidance on the general aim and purpose of the work”, much of which is still relevant today. The general aim was to be found in the “social and physical training” which could be given through both youth organisations and schools. The common task was to bring young people into a normal relationship with their fellows and to develop bodily fitness. It was recognised that these needs did not cease when young people left school, but that for most children, unfortunately, opportunities failed just at the stage where they were most wanted. The over-riding purpose was seen to be the “building of character”, and youth welfare was to take its recognised place in education. Young people were to be given a happy and healthy social life in association with their fellows, perhaps sharing in some common project, accepting and exercising the authority which a free relationship involved. In other words, much of the training was regarded as indirect, the result of these associations. This was a stirring document, full of challenge and encouragement.

29. The Ministry of Education made it clear in Pamphlet No (1945)[12] that the Youth Service was intended not merely to cover the provision of recreational facilities, but to provide for the training of young people (without compulsion) in “self-government and citizenship”, and to be a means of continued education in the widest sense of the term.

30. Following the Education Act of 1944, the Standing Conference of National Voluntary Youth Organisations issued a statement[13] in which they affirmed that the aim of education in their kind of organisation was not only “good citizenship” but also, “to live the good life” (and to some of them this meant Christian life in a Christian church).

31. All this indicates that the Youth Service has been seen, by at least some of those concerned, as something much more challenging than a rescue service and its units as much more than “streets with a roof”. Its purpose has been to help young people to make the best of themselves and act responsibly. This being so, we have sought to find out how the Service is living up to its aims and what are its present strengths and weaknesses.

ASSESSMENT OF THE YOUTH SERVICE

32. We have reviewed briefly the history of the Youth Service, the machinery by which it is operated, its cost and its present aims. We come now to the more difficult task of reviewing its performance in recent years and assessing its ability to sustain the burden we foresee for it.

33. First or all, the Youth Service has been kept in being throughout a difficult time, when the calls on the national resources have been very great. While on other fronts substantial advances have made, in this sector the line has at least been held. Without this holding operation, there would be no Youth Service to discuss. The headquarters of the main voluntary organisations have had enough help to make limited development possible in the field; and locally, while few areas have able to establish a Service such as the early circulars envisaged, most have able to ensure a small provision of clubs centres to meet the growing or youth. Local education authorities as a whole have increased their expenditure on the Service, and their youth officers or organisers have generally kept them aware of the most urgent needs. Some have notable achievements to point to; others have planned a groundwork on which it will be easy to build when the opportunity is provided. Interesting experiments have been tried, both by authorities and voluntary bodies. Overall, thanks to public funds, private generosity, and the timely help of trusts, and thanks even more to the resource and devotion or a great number of voluntary workers and a small band of paid (but often underpaid) ones, provision of some sort has been made for the needs of one in three of the young people between 15 and 21.

34. We have mentioned voluntary workers, and it is appropriate here to refer to the great importance of the voluntary principle in the Service. Voluntary attendance and voluntary help seem to us to be its chief strengths. Voluntary attendance is important because it introduces adult freedom and choice. Voluntary help is no less important. There are great numbers of people who are willing to give up their time to meet and talk with young people, and to help with the activities of youth groups, clubs and centres. The motives which have urged them to take up work in the Service are varied, but we are struck by the real concern for young people and the desire to help them at whatever cost which characterises most of these voluntary workers. It is vital for young people to understand that many of the older generation are genuinely anxious to make friends and to share their interests

35. So much for the strengths of the Youth Service as it is at present. We have made equally aware of its limitations and weaknesses; in policy, in machinery, and in performance. Since many of the weaknesses we have noted in the field stem from the prolonged financial stringency and consequent lack of drive, we must look first at the policy and the machinery for implementing it

36. We have referred to the importance of the Minister’s role in forming the national policy and guiding the development of the Youth Service. This part of his responsibilities has for some time past had a low precedence: during the ten years up to the end of 1958 the Ministry have not issued a single circular devoted solely to the Youth Service. During the same period there have been ten circulars which have had some bearing on it; all were concerned with education expenditure and seven of them imposed restrictions (the remaining three offering slight relaxation of previous restrictions). It is hardly surprising that this lack of encouragement has checked the momentum with which the Service was launched and has betrayed the high hopes of those who believe in it.

37. The Select Committee, in their Report of July, 1957[14], referred to this discouraging effect and put it down to lack of interest on the part of the Ministry of Education in the present state of the Service and to apathy about its future. The Minister’s observations on the Select Committee Report[15] point out that successive Governments have found it necessary to restrict the moneys they made available for the Youth Service, and “so long as this continues to be the case, it would be disingenuous if the Minister were to make statements purporting to encourage the adoption of policies either by local education authorities or by voluntary bodies which could not in fact be implemented without increased expenditure from public funds.”

38. It is not necessary for us to question decisions about the priorities in national expenditure which have been taken by each successive Government since the war; but we must point to the consequences as they have affected the Youth Service. First, the Minister has been unable to exercise effectively his function of guiding local education authorities in the development of policy and of ensuring the performance of their duties under the 1944 Act, since he has been unable to release the funds that would be necessary to implement the Act’s requirements. Second, the machinery for the Ministry’s direct grant aid, to which we have referred above, has never been developed: the system is a patchwork and there are obvious inconsistencies which ought to go. In fact recent grants have in some cases been barely enough to allow the organisations to carry out their basic work, and not enough to free them from chronic anxiety.

39. In view of these discouragements it is not surprising that when we come to examine the contribution of the next partner in the Youth Service, the local education authorities, we find a picture of somewhat haphazard development. Of course, since authorities have to frame policies to fit local needs, there are bound to be differences of system or approach as between one area and another: but where these differences are ones of efficiency they may reflect the apathy of some authorities or their loss of confidence in the Service. Some important authorities have no youth committee and no youth officer. Even authorities that value the Service show surprising variations in the way they go about things. These variations are generally the result of the differing views that authorities take or their relations with voluntary bodies and the extent to which the organisations should be brought into consultation. At one extreme are those that spend most of their money on clubs and centres of their own, at the other those that leave provision wholly to the voluntary bodies with the help of comparatively generous grants. The result of all this is that there is no accepted minimum of services which voluntary bodies of standing can expect from every authority as a matter of course.

40. Finally, we must look at the limitations of the Youth Service in the field, whether its work is being done by local authorities or voluntary bodies. In the first place, we must mention one general failing. We have for variety of method and a willingness to try new things, to adapt tried methods of work to the changing needs of young people, and to seek out groups in need of help. There is a great variety of organisations working in the service of youth: apart from the national voluntary bodies there are numerous clubs and activities by the Churches, local education authorities and groups. There is, of course, some variety of method, but there is less willingness than we should have hoped to break new ground. The type of boy or girl aimed at tends to be the same. This limitation may not be unrelated to some other weaknesses in the present-day Youth Service to which we must refer.

41. Lack of finance is at the root of several shortcomings we have noted: clubs that frequently have to function in dingy, drab premises; lack of equipment for the job; insufficient provision for outdoor recreation; and a failure to measure up to the needs of new towns and housing estates, summed up in the remark of the boy who described one of these estates as ‘a graveyard with lights’.

42. Leadership within the Youth Service has also suffered from shortage of money and lack of encouragement. Leaders feel unsupported and unappreciated: they look for some sign that their work is nationally recognised as important, but find it neither in official expressions of policy nor in the rewards of a salary scale for those who are full-time which would put the work on a level with cognate professions. They seem to themselves to be in danger of becoming cut off from the march of social and educational advance. And there is a considerable volume of evidence that full-time posts fail to attract good applicants

43. We believe that another factor enters here: that is the failure to provide a satisfactory structure for a professional service which of its nature is episodic rather than a life-time career; recruitment is still haphazard, salaries and conditions of service have never been agreed, and professional training is producing only a trickle of full-time leaders.

44. The partnership, envisaged in the early circulars, between Ministry, local education authorities and voluntary organisations, has not always stood up to the stress of circumstances. We have referred to the substantial variations that exist between the practice of local education authorities, their interpretation of their and responsibilities, and their relations with voluntary bodies. Lack of sympathy for youth work in some areas — fortunately a minority — has not always prevented progressive work being done in them, but the lack of consistency in policy over the country as a whole, together with the uncertainty about the scale of future grants, has undermined the confidence on which any partnership on a national scale should have been founded. As between local authorities and voluntary bodies there has been little co-ordination of effort, and consequently a temptation to create areas of influence rather than to seek common ground.

45. A particular in the Youth Service, for which all our witnesses have shown concern, is its failure to reach so many of the young people today. The figure often quoted was that the Service was attracting only one in three, and we found confirmation of this, first, in the replies of local education authorities to our questionnaire and, secondly, in the survey out by the Central Office of Information.

CHAPTER 2: Young People Today Part I: THE CHANGING SCENE

46. All times are times of change, but some change more quickly than others. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that in some periods the sense of change is particularly strong. Today is such a period. Our terms of reference require us to review the Youth Service “in the light of changing social industrial conditions and of current trends in other branches of the education service”. We think it useful to make a distinction here. We therefore look first at those changes which are comparatively objective, and more immediate in their probable effects. We consider secondly those less tangible elements which contribute particularly to the sense of change itself.

THE BULGE

47. For every five young people between the ages of 15 and 20 today there will be, in 1964, six young people. This increase will not be spread evenly across the country as a whole; but all areas and each kind of area will show some increase. In some new towns we expect it to be as much as five-fold. Between 1964 and 1970 the total number will decline gradually, but it will still remain substantially higher than today’s total. From 1970 there is likely once again to be a gradual increase. In sum, we have to plan for a consistently larger number of adolescents than we have been used to thinking of.[16]

48. Emergency measures were required and were taken to meet the impact of this ‘bulge’ on the schools. Similar measures are now being taken to meet the impact on technical colleges and universities of those from the ‘bulge’ generation who become students there. No comparable measures have so far taken to prepare the Youth Service for the needs of this increased population. Unless these measures are taken urgently the ‘bulge’ generations will leave school only to find a Youth Service inadequate to cope even with its earlier responsibilities.

THE ENDING OF NATIONAL SERVICE

49. During the past few years national service has kept roughly 200,000 young men between the ages of 18 and 20 out of civilian life. Its gradual abandonment during the next two or three years will cause this number of young men to remain available for civilian employment and leisure pursuits.

50. It has more than once been put to us strongly that national service was of great benefit to young men in developing not only physical abilities, but also self-reliance, and the capacity to work in a group and to accept organised discipline for a common purpose. Other witnesses disputed these claims and suggested rather that national service broke some important ties (of home, neighbourhood and work) at a crucial period in young men’s lives; and that it was dangerously boring to many young men or introduced them to some regrettable activities (excessive drinking, sexual promiscuity) without the support of a known environment. We have not felt it our duty as a committee to pursue this dispute to the point at which we could state a common conclusion. We give our attention therefore directly to the results of the ending of national service, to the retention by civilian society approximately 200,000 more young men between the ages of 18 and 20.

51. Three points emerge clearly. First, and in so far as it is true that national service did provide these young men with challenge and adventure suitable to their age and needs, the Youth Service must accept some of the responsibility for providing, in relevant civilian terms, this kind of opportunity.

52. Second, there should be among these older boys many who, if properly prompted, might play an important part in the running of existing organisations and of those self-programming groups.

53. Third, the freeing of this considerable number of young men will clearly strain the existing Youth Service unless changes are made within it. This group, together with that caused by the arrival of the ‘bulge’, will make the Youth Service responsible for a million more young people in 1964 than it had to cater for in 1958. The absolute increase on the 1958 figures will have dropped to about 770,000 in 1973, but thereafter the number seems likely to rise again. In 1960 the number of young aged 15-20 inclusive will be over 3½ million. Plainly, this suggests at least a prima facie case for marked expansion in all branches of the Service, in leaders (full- and part-time, paid and voluntary), in organisers, in training schemes, in premises, in outdoor facilities and in equipment.

PHYSIQUE

54. Today’s adolescents are taller and heavier than those of previous generations, and they mature earlier. Improved food and hygiene, better social conditions, physical training and medical treatment have ensured that most of them enjoyed better health in childhood than their predecessors. It has been estimated that the average gain per decade in this century in pre-adolescence is just over ½ inch in height and 1 lb. in weight, and that there is an increase to roughly ¾ inch and 3 lbs. during adolescence.[17] Individual variations for the onset of puberty can be considerable; but it appears certain that puberty is occurring earlier, and that the large majority of young people now reach adolescence, as determined by physical changes, before the age of 15.[18]

55. As we have suggested, today’s adolescents have usually been introduced to a greater range of activities and challenges in their physical education whilst at school than have earlier generations. More than one witness has impressed on us his conviction that young workers have considerable surplus energy which their work, and most of the more easily available facilities for leisure, do not always satisfy. Here is one plain and promising opportunity for the Youth Service. There has never been such scope to promote and encourage healthy physical recreation, both that of an organised kind and that which is founded in individual initiatives.

56. The changes we have outlined clearly have more difficult implications for school life, for further education and for the Youth Service. For the considerable emotional developments inseparable from puberty will now often be taking place in contexts earlier than those with which they have been habitually associated, e.g. during the last year or two at secondary modern school. The lesson for the Youth Service is also easy to state but difficult to practise. Obviously, experience of comradeship within the right kind of youth club may be of very great value at such a time. But if more youth clubs are to be of the right kind more youth workers will need to be aware of the psychological results of these changes, and of their implications for their own pastoral care.

CHANGING PATTERN OF WOMEN’S LIVES

57. The magnitude of the changes taking place in women’s lives makes hesitate to do more than draw attention to three points which we feel relevant to the type of provision needed for the adolescent girl. In the first place, the traditional balance of woman’s life is being altered by earlier marriage, by the shorter span of years now occupied in child bearing, and by the growth of employment outside the home after marriage. The shortening of the period between school and marriage is particularly relevant because it leaves less time for the girl to acquire social maturity and technical competence at her job as home-maker. Secondly, girls from homes where manual work has been the tradition are tending to move, and move more rapidly than their brothers, into non-manual work in a social setting other than that familiar to their circle. The potential strains in this are obvious. And this to our third point. These alterations and modifications to long-established patterns would suggest that girls no less than boys need further education after leaving school. In fact they get considerably less. The Youth Service, with the opportunities it offers for informal education, could make good some of these deficiencies, but fewer girls than boys are members of youth organisations, and much more thought will need to be given to ways of attracting them and studies made of their specific needs.

DELINQUENCY

58. During the past decade there have been increases, and in some cases marked increases, in the number and proportion of young found guilty of indictable offences. The facts of delinquency are on record, but we think it useful to give a brief summary at this point.

59. A recent report on “Trends in Teenage Delinquency”[19] attempts to show for a ten-year period (1946-1956), the trend for various broad types of offences, the figures of indictable Offences having been supplemented by the addition to them of related and often complementary non-indictable offences known to the police. They are striking figures. The incidence of convictions of youths aged 17—20 for drink offences showed a five-fold increase in these ten years; the incidence for violence roughly trebled, and for both sexual offences and disorderly conduct, it doubled. The pattern for boys aged 14—16 was different. In the two groups of offences, theft and disorder, where the incidence of convictions per 10,000 boys was heaviest, there was a tendency for improvement in the last five years of the period; but in the personal field of drink, violence and sexual offences there was deterioration as with the 17—20 age group.

60. For girls in the 17—20 age group. there was no apparent deterioration in any sector during the first five years. In 1951, however, there was a sharp increase in the incidence of convictions in the drink, disorder, and sexual groups of offences; and in 1955—56 there was another increase. For girls aged 14—16, there was some increase in the incidence of convictions for drink offences; but the general levels for all offences except theft were substantially lower in this age group than in the 17—20 group of girls.

61. The incidence of suicide and attempted suicide more than doubled in this period for young people aged 17—20 and, as if to suggest that the crimes reflected personal tensions rather than social wants, the figures did not reveal any substantial rate of change in such offences as theft

62. An increase in offences reported or in convictions may on the one hand be due to a change of attitude, on the part of the police, magistrates and public, and on the other to an increase in the actual number of offences. Nevertheless on balance these trends must have some substance

63. The tables in Appendix 9, derived from the annual reports on criminal statistics published by the Home Office, show the rates in various age groups of indictable offences in the years 1938 and 1946—1958. It will be seen that these rates have shown serious increases for adolescent groups. The present upward surge (1958) in offences of youths aged 17—20 looks particularly grave. And the 14—16 age group has reached a rate of more than 2,000 offences per 100,000 Of the population, which is higher than the rate for the previous peak year. 1951. [20]

64. Is it possible to associate this crime wave among young people with disturbed social conditions? An important paper read to the British Association in 1958 by Mr. Leslie T. Wilkins of the Home Office Research Unit[21] succeeds in the tentative definition of two more than usually delinquent generations. The first crime-prone group were those born in the years 1926—1928: the second, those born in the seven years period 1935—36

to 1942—43. The children of both groups reached the age of four to six during periods of widespread social disturbance: for the first it was the great depression, with its consequent unemployment, which began in 1929 and mounted in violence until 1934, and for the second, of course. it was the second world war. It would seem that personal disturbance leading eventually to delinquency might be associated with the shocks of the last pre-school year or the first school year, years in which children first develop social sense. Yet as Mr. Wilkins shows, this interesting finding is not sufficient explanation of the current crime-wave in males between 17 and 21. The age group which passed through their third to sixth year during the war is expected to be more crime-prone than other age groups of boys and girls. But in fact the observed crime rate has turned out to be far in excess of expectation. In other words the present phenomenon cannot be dismissed as “only to be expected in view of their childhood experiences”.

65. In one sense, therefore, we think we can speak of a new climate of crime and delinquency. We have been made intensely aware of this and we accept the significant public warnings of judges and police chiefs. It is easy of course to exaggerate the incidence of delinquency. Even after all the increases, it involves in any one year only about 2 per cent of boys aged 14 and under 21 and only 0.2 per cent of girls of the same age group. On the other hand, of the total number of persons found guilty of indictable offences in 1957, roughly one half were under 21, and 30 per cent were aged 14—20 inclusive. Therefore whether the figures are large or small in relation to the total population, the crime problem is very much a youth problem, a problem of that age group with which the Youth Service is particularly concerned and towards which the public rightly expects it to make some contribution

66. The present rise of crime among the young is against expectation in another sense. Sociologists have always traced a strong correlation between poverty and crime. The poorest and most socially deprived elements of a population were always those who had most to gain and least to lose from active crime. Reformers confidently expected that improvements in social conditions would progressively reduce the incidence of every sort of crime. True this was a theory which tended to overlook upper class crime and to discount personal reasons for crime, but by and large everyone expected it to work out more or less accurately and it is grievous that hopes have been so much disappointed. If we can no longer look to the old economic causes for crime we must search for new ones, or for personal or social ones which override the declining economic factors.

67. Many explanations have been advanced—the second world war. The hydrogen bomb, the welfare state, the limitations of opportunity in a boring society, the growth of a sense of violence in a century infamous for violence of every kind. We do not feel that we can point with any certainty to any one particular cause or combination of causes. Nothing in the evidence we have received directly associates the crime wave among the young with any special new social or national condition. It does seem true, however, that society does not know how to ask the of the young, that as a whole it is not much more concerned with them than to ask them to earn and consume. It is necessary no doubt to do both, but man’s deepest needs are not satisfied by a mechanical participation in an economic process.

68. We do not think it is easy or wise to speak glibly of a delinquent younger generation and a law-abiding older generation. This is only half the story. What, to a person of forty or fifty, may show itself as a general malaise, a sense of emptiness, a quiet rejection of social responsibilities or a cautiously controlled cynicism may show itself in an adolescent as an act of wanton violence, a bout of histrionic drunkenness or a grasping at promiscuous sexual experience. There does not seem to be at the heart of society a courageous and exciting struggle for a particular moral and spiritual life — only a passive, neutral commitment to things as they are. One cannot, in fact, indict the young for the growth of delinquency without also indicting the older generations for apathy and indifference to the deeper things of the heart

69. It is natural to that the Youth Service should be able to do something about this state of affairs. It certainly must try, but it cannot be expected to deal with causes of delinquency which may born long before teenage, or with the ethos of the whole society. It can only be effective indeed, and then perhaps to a limited degree, if it carries society with it in its difficult task. Before we speak of what it might do, it is necessary to say that the effect of the crime increase is not to turn every teenager into a delinquent but to create an atmosphere in which it is increasingly difficult for social and youth workers to succeed and in which psychological difficulties are placed between even the well-meaning young and the agencies which would like to co-operate with them. The climate is particularly turbulent with the sense of increasing violence and destructiveness — not always indictable — among sections of the young. This acts disastrously in several ways. First, it digs a gulf between the young generally and the law-abiding older sections of the community, which it almost impossible to bridge. Misunderstandings grow. Secondly, it deeply affects the young who would themselves never become violent. They are unsettled by the success of the lawless in society. This becomes the more true the more society fails to bring offenders to trial. Every teenager in a congested area knows of offences committed in the neighbourhood and not discovered. He hears them boasted about in public places. He knows that a life or crime, rarely discovered, is possible, and this shakes his faith in the order and dignity of the society in which he lives. The whole society comes to look hypocritical. Thirdly, crimes of violence (particularly if undiscovered) terrorise the other young. In one sense they are meant to. Bragging lawless teenagers hope that their contemporaries will accept them as stronger than society and above its laws. This must seem to be true when a convicted youth re-appears in his old haunts and ready for his old pursuits, apparently unintimidated by his experience in court, and on occasions even enjoying enhanced status within his group. Fourthly, crimes of violence create an atmosphere in which older people are unwilling to intervene to stop other crimes because they fear acts of violence against themselves. Everyone who has moved among teenagers in certain inner suburbs of big cities has had to face this moral dilemma at some time or another. The retreat from responsibility on the part of the general population for fear of reprisals leaves the police isolated in their tasks and hurt by lack of public support. It has a deadly effect on the young who wish to law-abiding, and who read from this the growth of social pressure to tolerate or at least not to oppose the tough in any risky way. They draw their own conclusions and play safe themselves.

70. What has to be asked for in the face of this moral withdrawal is a clear and strong indication from the whole of society of its social condemnation of rising violence and destructiveness, and of personal crimes, among the young. This is a necessary preliminary to social therapies. Only if society knows what to condemn can it know what to heal. It ought never to remove by anything it does the sense of personal responsibility for their acts from the young.

71. On the positive side, given such a new national feeling, the Youth Service can do much to make the appeal of the good society stronger than the dynamic of wickedness. Reformed and enlarged and supported in the manner in which we sketch it in succeeding chapters, it should be far more capable of granting new and adventurous opportunities to the young than are at present possible and should engage the energies of many more young people in the acquisition of personal skills, or the delights of good social life, and in forms of service to the community. As it grows it will draw, not only more of the good and law-abiding, but also more of the critical and restless and those who are natural but reckless leaders of their age groups. It will not do so by a form of indoctrination — we feel that the Youth Service we sketch rules that out — but by the provision of new freedoms for the next generation to come to maturity, and so to social responsibility in its own way. But, we repeat, a socially unsupported or spiritually isolated Youth Service could not succeed.

HOUSING

72. Since 1945 nearly 3 million houses and flats have been built in England and Wales. This progress in re-housing, together with the school building programme, and the improved working conditions and commercial facilities for leisure, have accustomed many teenagers in the present generation to new and better standards of physical provision which have implications for the Youth Service which we consider in Chapter 5. It must be remembered, however, that there is a darker side to the picture which also has its lesson to teach

73. The bricks and mortar of the homes of a great many people were laid to meet the needs of a different age, which had to accept lower standards of sanitation and physical provision. It is estimated that about one-third of the national housing stock is over seventy-five years old, and much of it has been intensively used by many families who sometimes share such basic equipment as water closets. Whilst the number of slum dwellings is happily declining it is obvious that the development of satisfactory relationships in many families is still hampered by inadequate housing provision. The younger members of such families are Often not encouraged or inclined to bring their friends into the home, and by tradition their meeting places have been the street corners or the local cafés and, for some, the youth clubs

74. It is also important to recognise that in many industrial towns the areas with sub-standard housing are undergoing fundamental social changes that have sometimes led to serious disturbances among some of the young people. New and strange faces appear on the doorsteps and congregate in the streets as workers from many lands find a job and a home in Britain. The integration of these families brings problems, and has sometimes created a sense of insecurity and a fear among the established community that housing standards will deteriorate further. Housing conditions do not completely explain the violence shown by some youths in these areas, and the prevalence of lawless gangs is not a new social phenomenon of the slums. However these racial outbursts present a new problem and seem paradoxical in this age when young people of all races and nationalities seem less different and share common interests such as jazz and football and often a common culture.

75. For the young people enjoying the first-class housing, schools and shops of the new towns, the new housing estates and blocks of flats, the problem is different but no less challenging. Homes are more attractive but beyond, nearly all are strangers. The street corners are quiet and uninviting, with their searching sodium lamps, and their lack of familiar lights and smells. It is all houses or flats, perhaps occasionally a pub or a church, but rarely a coffee bar or a place provided for young people to meet. The present generation of teenagers, the first in these towns and areas, is cut then from the traditional forms of face-to-face social education in the long established neighbourhoods

76. It is hardly surprising that many young people get out of these areas where boredom reigns, as quickly and as often as they can. They make for the nearest established town or simply the nearest main road where they can race up and down on their motorbikes. This is a problem for the Youth Service to which we revert later.

EDUCATION

77. The Central Advisory Council for Education (England) was asked in March, 1956, “to consider, in relation to the changing social and industrial needs of our society, and the needs of its individual citizens, the education of boys and girls between 15 and 18 and in particular to consider the balance at various levels of general and specialised studies between these ages and to examine the inter-relationship of the various stages of education”. Although at the time of submitting our Report their findings have not been made public, we know that the Council will be giving a very full account of the educational needs of boys and girls aged 15—18. For this reason we have not tried to make a complete analysis of educational changes since the war but have confined ourselves to a few which are of direct relevance to the Youth Service. All that we say about education in this section is overshadowed by the unanswered questions about the raising of the school leaving age and the establishment of county colleges. We consider in Chapter 9 the need for a Youth Service when county colleges come into being and the relation between these two forms of educational provision for young people.

78. The new system of secondary education for all, brought into being by the Education Act of 1944, is still not fully developed; but there has recently been a much keener sense of its potential. Not only has the raising of the school leaving age to 15 become acceptable, but in many areas parents and their children are demanding more schooling. The Ministry’s Annual Reports show the substantial increase in the number of pupils staying on at school beyond 15, an increase which is more than proportionate to the size of the relevant age group. There has also been a steady growth, both absolutely and proportionately. in the number of 17-year-old pupils in grant-aided and recognised schools in England and Wales. It seems likely that, this trend in the demand for extended education will continue, even while the period of compulsory school attendance ends at 15.[22]

79. In December, 1958, the Government announced a five-year programme of educational advance in the secondary field beginning in 1960 and costing £300 million.[23] The aim is to provide opportunities for the individual boy or girl to go as far as his keenness and ability will take him. The programme will allow for the building of new schools still needed to meet local increases in the number of pupils, for the remodelling of serviceable old buildings, for the reorganisation of the remaining all-age schools and for the general improvement of secondary provision

80. Against these gains must be set the continuing difficulties under which many secondary schools are labouring. They are now facing their own problems of the “bulge”, just as workers in the Youth Service will have to meet theirs in the early ‘sixties. Many classes are overlarge; in certain subjects there is a scarcity of specialist teachers; certain areas find it hard to attract and hold sufficient teachers of all kinds. The lengthening of the normal course of training of teachers from two years to three in 1960, however beneficial in the long run, will prolong for a period the present strain on the staffs of schools.

81. Once the strain is eased, the effects of the strengthening of the secondary system should make themselves felt. Even as things are, the material conditions for art and crafts, music and physical recreation are continually improving. Even now schools of all kinds are showing a keener concern for social education. Clubs and societies, foreign travel and social service are increasingly regarded as a normal part of school life in which the pupils are encouraged to undertake a fuller responsibility. A very recent Ministry circular[24] suggests that club rooms, common rooms and quiet rooms can be provided even in old school buildings. The Youth Service must expect young people in future to be more critical of its standards and more exacting in their demands; and it must take account of the schools’ stronger sense of social purpose and of what is being done to encourage independence and responsibility in the adolescent.

82. There are interesting developments in other branches of education. The growing strength of the youth employment service over the last ten years has meant for many young people an easier passage from school to work and a greater stability and confidence after they have taken up employment. Moreover the growth of extended courses in secondary schools is leading to a stronger link between schools and technical education. The expansion of technical education is dramatic indeed. In 1956 the Government published a White Paper[25] to announce an £85 million programme for the expansion and improvement of technical education over a period of five years, and this is to be followed by a supplementary programme for a further three years. Two features in the development of technical education are of particular interest to the Youth Service

83. The first is the increase in the number of young people released by their employers for part-time courses during the day. The White paper envisaged that the number of 355,000 young people so released during 1954—55 would be doubled by 1962. The Ministry’s 1958 Annual Report shows that good progress has been made so far, but that the rate of increase has slowed down. It is also plain that in day-release courses the number of girls is much smaller than the number of boys and that the number of semi-skilled young workers is much smaller than the number of those training to be technicians or craftsmen. Even as it is, the growth of part-time release means that fewer young people are attending vocational classes in evening institutes and that more young people have more evening leisure than they had. It is also providing useful experience for those who will have to plan the county colleges of the future; the pity is that experience of part-time release for girls and for the semi-skilled is still so slight

84. Secondly, the development of a liberal element in technical education bas been given direct encouragement by the Ministry. In Circular 323, issued in May, 1957, the Minister made it clear that the need for this development was already widely recognised, and he therefore encouraged further discussion and experiment. “Only so will students develop a broad outlook and a sense of spiritual and human values as well as technical accomplishment.” Close contact was encouraged between student activities and the industrial clubs and societies with which students might be associated. Thus the trend is towards a broadening of treatment and content and, as in secondary education, towards a richer social and corporate life, giving students the opportunity to share in a wide range of activities and to be responsible for organising them. In this climate it is possible that some of the local colleges of further education will begin to develop those relations with the Youth Service which will be expected of the county colleges of the future

85. To summarise: both secondary and technical education are in process of being widely expanded and improved; opportunities are increasing for those boys and girls who do not go to grammar schools; many schools and colleges of further education are broadening their concepts of study; social education and physical recreation are receiving more attention. As we point out at greater length in Chapter 3, there is a striking contrast between what is provided for those young people – the minority – who continue their formal education, full-time or part-time, and what is available for the remainder who have only an impoverished Youth Service to turn to.

SOCIAL SECURITY

86. Since we have mentioned changes in the fields of education and housing, we cannot ignore developments in social security and welfare which have occurred during the last generation.

87. This period has witnessed the introduction of the National Health Service, the raising in real value of a comprehensive collection of social benefits together with the introduction of new benefits, and the promotion of many new welfare services by statutory, industrial and voluntary organisations. This is relevant to our Report in so far as it has helped to establish a climate of security which was largely absent at the beginning of the period. In particular, the provision of family allowances may be a factor in the earlier marriage and the raising of a family; this, in turn, has social consequences which we mention elsewhere.

88. It is not possible for us to assess the impact on youth which social security has made. There are undoubtedly those who hold that it has led to a less responsible citizen: this perhaps springs from an insufficient realisation that it is made and paid for by nearly every member of the community. On the other hand, it can be argued that with the banishment of fear and want, a better citizen will evolve. It is sufficient that we should draw attention to this considerable change, which has taken place since the Youth Service was introduced, as it is part of the background of young people today.

MONEY TO SPEND