Article: What’s the “problem” with Irish youth work? A WPR analysis of value for money policy discourse and devices

Sinead McMahon analyses a key Irish youth work policy document, the Value for Money and Policy Review of Youth Programmes. Using Bacchi's (2009) WPR analysis, she argues that the document constructs youth work as ‘problematic’ and in need of reform.

Introduction

Since 2011, Irish youth work has experienced ongoing reforms under the problematising gaze of policy makers. In this article I draw on the research I undertook as part of a doctoral study that explored the key role of the Value for Money and Policy Review of Youth Programmes (VFMPR) (DCYA, 2014) in helping to construct images of youth work as ‘problematic’ and in need of reform.

Context and Background

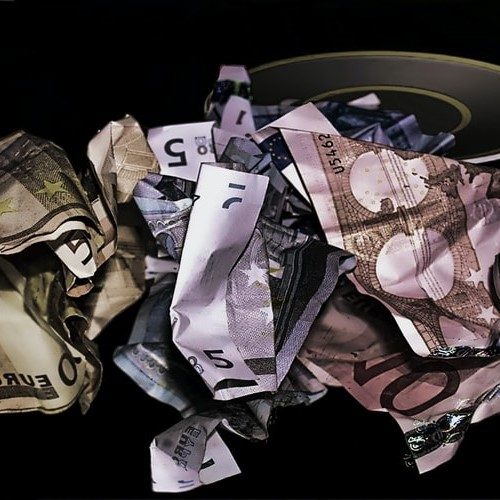

Irish youth work appeared to flourish during the Celtic Tiger years from the mid-1990s up to 2008. This ‘golden era’ included significant increases in state funding as well as the publication of the Youth Work Act resulting in improved recognition for youth work (Devlin 2008, 2010). There were other positive policy developments and in 2007 the Government’s overarching National Development Plan made significant commitments to ‘supporting the youth work sector’ promising the implementation of a National Youth Work Development Plan and the setting up of a National Youth Work Development Unit (Government of Ireland, 2007:246 – 247). However, the global economic crash in 2008 negatively impacted the promised supports and instead a programme of austerity cuts hit youth work services, resulting in a 31% decrease in government funding (NYCI, 2019). These funding cuts had serious consequences for youth work services and for practitioners including service reductions, pay cuts and redundancies (NYCI, 2012, Melaugh, 2015). In addition to facing damaging financial constraints, the youth work sector was also asked to implement a new quality assurance system. This left youth work organisations and youth workers exhausted from ‘doing more with less’ and also worried about the future survival of youth work (Melaugh, 2015, Jenkinson, 2013). Since 2016 improving economic conditions have led to some restoration of youth work funding, though the National Youth Council of Ireland (2020) estimates that despite increases, the overall funding situation in 2020 was still 12% below 2008 figures. Furthermore, they suggest that youth work was disproportionately affected by funding cuts and that as government spending has increased ‘youth work services have not received their fair share’ (NYCI, 2020:9).

While funding cuts have had very real impacts on youth work provision it is the accompanying reorientation in policy discourse towards a reform agenda that I focus on here. According to MacCarthaigh (2015) the economic crisis provided a legitimising backdrop for ‘unprecedented’ public service reform in Ireland. The creation of a Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (DPER) by the Fine Gael government in 2011 signalled just how important a reform agenda would be to this new government. At the same time the new government also established Ireland’s first Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) which included responsibility for youth work. In one of its first published reports, A Comprehensive Review of Expenditure (DYCA, 2011:6), the Department was quick to share its ambition to ‘be a model for public service reform’. The report detailed a wide range of savings and rationalisations that needed to be achieved by the Department and indicated that it was ‘imperative that youth work funding streams would be reformed’ (ibid: 20). Despite the substantial cuts being shouldered by the youth work sector at the time and alongside the commencement of a new quality assurance system, it seemed that policymakers in the new Department of Children and Youth Affairs wanted even more, evidenced by increasing emphasis on the need for a ‘reform process’. At this initial point, the policy discourse suggested that reform was a matter of simple administrative restructuring. Reform would just involve collapsing multiple funding schemes into one to achieve savings in administration costs whilst at the same time allow youth services more flexibility ‘to respond to local needs’ (ibid). Soon after, in its first Statement of Strategy the Department extended the depth of required reform so that youth work funding schemes would need to be ‘renovated and reoriented’ (DCYA, 2012a:30, emphasis added). During parliamentary debate, the then Minister for Children and Youth Affairs tabled an amendment to a motion set down by Senator Jillian van Turnhout in support of the value of youth work. The Minister’s amendment was less in keeping with the spirit of support and instead problematised youth work as in need of ‘ongoing’ reform with a ‘much sharper focus on quality, outcomes and evidence-based practice’ starting with ‘progressing value for money reviews of youth work funding’ (Fitzgerald, 2012).

In late 2012 the DCYA triggered a public sector reform device called a Value for Money and Policy Review of three youth work funding schemes for disadvantaged youth promising that its outcomes would ‘inform the future provision of quality youth service’ (DCYA, 2012b: 24). The VFMPR was published in 2014 and DCYA acted quickly to translate the report’s recommendations into practice using ‘sample’ youth work projects:

The VFMPR made twelve recommendations, and we’re working on all twelve at the same time so there’s a lot going on. We’re trying out new ideas through sample projects and learning from the results, both good and bad. (DCYA, 2018:2)

Six years of experimentation and reform in local youth work projects have culminated in the roll out of the new UBU: Your Place Your Space funding scheme for targeted youth programmes on July 1st 2020 (see www.UBU.ie). The reform of youth work funding has impacted both at the administrative level as well as on the ground within local projects. At the administrative level there has been a radical restructuring of targeted funding programmes into one. Local statutory bodies have replaced national voluntary youth work agencies as the new funding intermediaries between youth organisations and DCYA. There have been significant changes to the funding contract that has direct implications for the narrowing of youth work practice including specifications on the percentage of time to be given to working in universal activities (20%) and targeted activities (80%). Youth work practice is now governed by new ‘operating rules’ that allow much less discretion for youth work practitioners. The ‘rules’ provide for ‘nine types of structured interventions’ to be used by youth workers in the scheme and require that youth work projects are oriented to the achievement of seven pre-defined personal and social outcomes for young people (see DCYA, 2019:44 – 52). The new Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, Roderic O’Gorman, referenced the UBU initiative as ‘the most significant reform of youth services ever undertaken’ (O’Gorman, 2020). It is interesting to note that behind the good news story that youth work funding is being slowly restored after a period of austerity, the problematising policy discourse centred on youth work reform is still ‘ongoing’. Value for money discourse and devices have played a significant role in this.

The Study

Cognisant of the radical shift in government policy discourse as it moved from one of support for youth work in 2007 to one that increasingly and incessantly pointed to youth work as problematic and in need of reform from 2011 onwards, I was interested in trying to understand how youth work had become the object of such an intense reforming gaze. I designed my doctoral research as a critical policy study and I chose the VFMPR policy as a key ‘entry point’ for analysis (Bacchi, 2009). I positioned the study around the VFMPR because I saw it as a clear governing moment for Irish youth work, where ‘givens become questions’ (Bacchi 2012:2). The VFMPR document stood out from other contemporaneous youth policy documents because it took a direct interest in the conduct of youth work practice and because it recommended changes for how youth work ought to be delivered and evaluated. This VFMPR has also been noted by Irish civil service commentators as being unusual because of the extent of commitment to seeing through full implementation of the report’s recommendations (Madden, 2020).

To undertake the research, I engaged Carol Bacchi’s (2009) ‘What’s the Problem Represented to be?’ (WPR) method of critical discourse analysis. Bacchi’s (2009) approach, influenced by governmentality theory, is to study problematisations, that is, to study how some things get produced as problems. For her, government policies are good examples of problematisations, places where we can see problems being framed and shaped. The WPR method involves interrogating policy documents using a set of prompts to ‘work backwards’ from the solutions often presented in policy documents, to trace the implied problems and to analyse their underlying discourses, rationalities as well as their effects. For this article I will only address the first analytic prompt of the WPR framework which asked ‘what kind of problem is youth work represented to be in the policy discourse of the VFMPR?’. When doing policy analysis using WPR it is necessary to identify ‘problem representations’, that is, how “problems” are actively constructed and presented to us in policy discourse (ibid). My study identified that through the policy discourse mobilised in the VFMPR youth work is constructed as a set of three dominant, value for money ‘problems’ including: youth work as a problem of risk; as a problem of underperformance; and as a problem of proof. In the following sections I will give just some examples of how the policy device and discourse of the VFMPR helped to produce these youth work ‘problems’.

Youth Work as a ‘Problem’ of Risk

Within the policy discourse of the VFMPR, clear efforts were made to represent youth work as a problem of risk. The word ‘risk’ appears 73 times in the document indicating an explicit interest in exploring this ‘problem’. Indeed, the very act of making youth work funding the subject of a formal value for money review had the effect of signalling the suspicion of policy makers and making this visible to youth workers and providers. Yet, despite a thorough economic analysis, the VFMPR concluded that it could not in fact determine whether the selected programmes provided good value for money or not. So instead of easing suspicions, the VFMPR actively produced uncertainty and an image of youth work as economically risky when it said:

This review of …youth programmes has raised a number of issues that have significantly hampered the authors’ attempts to determine value for money, whether of the programmes as a whole or in discriminating relative performance by individual service providers within the programmes. This is obviously an unsatisfactory situation for programmes, which accounted for approximately €128 million public investment for the period under examination (p128).

The VFMPR also utilised the problem of ‘significant information asymmetry’ often associated with business contracts as another method to construct youth work as risky. Here it is suggested that youth work providers as ‘contracting agents’ had access to information that the ‘commissioning principal’ (i.e. DCYA) did not, making it a ‘key risk’ (p184) for DCYA. It pointed to ‘misleading’ and ‘incorrectly’ calculated data produced by youth work providers, saying for example:

… output data gleaned from annual service activity reports proved unreliable, requiring significant amounts of ‘cleaning’ and ultimately sampling to attempt to reconcile often misleading information (p37).

Despite acknowledging that DCYA was in possession of large amounts of qualitative reporting from youth work services, the VFMPR instead zoned in on the issue of numerical data as evidence of the information risks faced by DCYA. In doing so, the policy discourse of the VFMPR produced an image of youth work as a risky agent who returns dirty data that requires ‘cleaning’. On the basis of this asymmetrical information risk, the VFMPR installed a further problem of a ‘governance gap’ (p48) between DCYA and youth work organisations. The VFMPR concluded that there was ‘deficient governance’ of youth work programmes by DCYA who, it implies, failed to adequately manage these risks:

The review found that the governance system overseeing the youth programmes was deficient in terms of its configuration, operations and capacity. Human service programmes such as the youth programmes under examination require considerable oversight …and risk management (p129).

Once the problem of economic and governance risk was constructed, it became possible to legitimise the need for increased state surveillance of local youth work projects and practice. A key recommendation of the VFMPR was to enhance the governance capacity of DCYA and in particular to introduce a new layer of state-based governance structures at local level that could closely monitor youth work as a risky agent.

Youth Work as a ‘Problem’ of Underperformance

A second problem representation in the VFMPR is the production of youth work as underperforming. ‘Performance’ is mentioned 162 times in the document though the term ‘underperformance’ appears just once. However, the one and only appearance of the term is instructive:

No specific criteria appeared to be in place regarding underperformance…The Youth Affairs Unit indicated that in recent years there had been no movement in terms of new entries nor had there been exits from any of the programmes due to poor performance. Given the scale of investment in these programmes and the breadth of deliverables, it is plausible to assert that there had been variable performance, but that any distinctions remained undetected (p49).

Here the policy discourse of the VFMPR actively produces of the problem of underperformance even though there is no actual evidence of such a problem. The VFMPR suggested it was ‘plausible’ to assume that underperformance exists (due to the number of providers and scale of funding) but that it is just ‘undetected’. The problem of underperformance was further implied throughout the VFMPR in references to youth work organisations as types of ‘performers’. For example, it suggested that ‘poor performers can be distinguished from satisfactory and exemplary performers’ (p43) and that there was a need to be able to ‘discern between weaker and stronger performers’ (p129).

Having produced the problem of undetected underperformance, the VFMPR then opened up a host of related subproblems. These were referred to as ‘measurability complexities’ that hindered ‘simple performance calculations’ needed to help distinguish good and poor performance (p87). The VFMPR critiqued the absence of outcomes data and reporting for youth programmes (p99); the huge range of diverse programmes and practices that did not lend themselves to being ‘uniformly codified’ (p128) meaning their performance could not be measured in the same ways or compared to each other; and the lack of quantified data from providers who instead submitted volumes of qualitative data that were said to have ‘obscured performance analysis’ (p101). Once these sets of problems related to undetected underperformance and measurement complexity were constructed, the VFMPR concluded that governance reforms were necessary to bring ‘considerable oversight’ to the problem (p129). In an effort to make youth work perform through reform the VFMPR recommended that a ‘performance framework’ be introduced. The framework would involve: increased monitoring by local state bodies; clear criteria to aid the targeting of ‘at risk’ young people; and outcomes measurement for the production of youth work data that would be quantified, calculable and database friendly.

Youth Work as a Problem of Proof

The third way that youth work is constructed as a ‘problem’ in the policy discourse of the VFMPR is in representing it as a method of work with young people that is unproven. Throughout the text there are references to youth work as ‘elusive’ (P109), the youth work relationship as ‘enigmatic’ (P109) and its outcomes as ‘intangible’ (P164). As part of the value for money evaluation, the VFMPR analysed the role of knowledge in youth work programmes and practice. The text significantly problematised the application of knowledge at practice level, saying it found ‘only presence of theory as opposed to widespread and deep application of theory to practice across programmes’ (p95). The VFMPR argued that it could not find ‘proof of impact’ (p86) and pointed to the lack of evidence to support causal links between practice and outcomes for young people (p183, Footnote 32). Despite an acknowledgement of a newly emerging evidence-base in Ireland, the VFMPR still determined that there was the remaining problem of an ‘imperfect ‘what works’ evidence base’ for youth intervention (p96). In other words, there still remained a contested field of uncertain evidence that required practitioner discretion in the translation of this evidence into practice.

By producing the ‘problem’ of an ‘imperfect evidence base’ the VFMPR opened a space to recommend a variety of knowledge solutions for youth work. Though Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) are reified in the VFMPR discourse as the ‘pinnacle’ instrument for achieving ‘conclusive evidence regarding impact’ (p122) and for the fact that they are ‘undoubtedly easier to monitor from the centre’ (p123) they are also acknowledged to be expensive and have limitations that might make them questionable value for money. Instead, a Theory of Change model aligned with seven proximal outcomes for young people are recommended for use in a ‘reformed scheme’ (p180).

Conclusion

For readers of Youth and Policy based in England, the policy constructed youth work ‘problems’ outlined above will be familiar. In 2011 the House of Commons Education Committee review of youth work significantly problematised youth work as unproven, as lacking evidence, despite rafts of personal testimony from young people and youth workers about the value of youth work (de St Croix, 2016). Also, the Young Foundation’s work (Moullin et al, 2011, McNeil et al, 2012) relied heavily upon value for money discourse in producing youth work as risky and underperforming leading to new economic methods for measuring and calculating youth work impact using outcomes. It is that very same set of outcomes that now takes centre stage in the reformed, targeted youth funding scheme in Ireland (see DCYA, 2019). These similarities indicate the role of ‘policy travel’ (Bacchi, 2009) in making youth work problematic across jurisdictions. There has been significant debate in England about the ongoing neoliberal reform of youth work there (e.g. Bunyan and Ord, 2012, IDYW, 2014, de St Croix, 2017, McGimpsey, 2017, Davies, 2019, Taylor et al 2019). However, in the Republic of Ireland, with the exception of work by Kiely and Meade (2018) and Swirak (2015, 2018) this type of analysis has been relatively absent, underlining what Jenkinson (2013:15) refers to as the ‘predominantly conservative nature’ of Irish youth work.

While austerity-based funding cuts to Irish youth work have received a lot of attention and critical commentary the accompanying neoliberal policy and funding reforms have not. Given the central role that value for money policy discourse and devices have played in the roll out of the new UBU targeted funding scheme this article is a timely reminder of the work that policy does to re-form youth work. The ‘what’s the problem represented to be?’ method of policy analysis encourages analysis of the work that policy does to create youth work ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’. The ‘problems’ of youth work as risky, as underperforming or as unproven have been produced by the choices made by Irish policy makers to solely apply an economic oriented, value for money approach to the evaluation of youth work funding schemes. Crucially, WPR policy analysis enables us to gaze back at this policy work to reproblematise it. For Irish youth workers now caught up in reorienting youth projects and practice to align with UBU ‘operating rules’ (DCYA, 2019) this article also draws attention to the importance of doing critical policy analysis as a ‘first and vital skill of practice’ (Davies, 2010).

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 1 October 2021

References:

Bacchi, C. (2009) Analysing Policy: What’s the problem represented to be? New South Wales: Pearson Australia.

Bacchi, C. (2012) Why study problematisations? Making Politics Visible, Open Journal of Political Science, 2(1), 1 – 8.

Davies, B. (2010) Policy analysis: a first and vital skill of practice In: Batsleer, J. and Davies, B., eds. (2010) What is Youth Work? Exeter: Learning Matters. pp7-20.

Davies, B. (2019) Austerity, Youth Policy and the Deconstruction of the Youth Service in England, Palgrave Macmillan.

Bunyan, P. and Ord, J. (2012) ‘The neoliberal policy context of youth work management’ on Ord, J. (ed.) Critical Issues in Youth Work Management, London: Routledge, pp19 – 30.

Department of Children and Youth Affairs, (2011) Comprehensive Review of Expenditure, Vote 43 [online]. Available at: dcya.gov.ie/documents/publications/cre2011.pdf [accessed 28th November 2014].

Department of Children and Youth Affairs, (2012a) Statement of Strategy 2011 – 2014. Dublin: DCYA.

Department of Children and Youth Affairs, (2012b) Annual Report of the Department of Children and Youth Affairs, Dublin: DCYA.

Department of Children and Youth Affairs, (2014) Value for Money and Policy Review of Youth Programmes, Dublin: DCYA.

Department of Children and Youth Affairs, (2018) Reforming Youth Funding: DCYA Update Newsletter, Dublin: DCYA.

Department of Children and Youth Affairs, (2019) UBU Your Place Your Space: Policy and Operating Rules, [online] https://ubu.gov.ie/resources [Accessed on 10th November, 2020].

de St Croix, T. (2017) Youth work, performativity and the new youth impact agenda: getting paid for numbers?, Journal of Education Policy, pp1-25.

de St. Croix, T. (2016) Grassroots youth work: policy, passion and resistance in practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Devlin, M. (2008) Youth Work and Youth Policy in the Republic of Ireland 1983-2008: Still Haven’t Found What We’re Looking For? Youth and Policy, 100, pp41-54.

Devlin, M. (2010) ‘Youth work in Ireland: Some historical reflections’ In: The history of youth work in Europe: Volume 2. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Fitzgerald, F. (2012) Youth Work: Motion, Seanad Eireann Debate 12th December 2012, 219(9), [online] https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/seanad/2012-12-12/29/ [Accessed on 15th November, 2020].

Government of Ireland (2001) Youth Work Act 2001, Dublin: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland (2007) National Development Plan 2007 – 2013: Transforming Ireland, A Better Quality of Life for All, Dublin: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland (2013) Appropriation Account 2013 for Vote 40 Children and Youth Affairs [online]. Available at: https://www.audit.gov.ie/en/Find-Report/Publications/2014/Vote-40-Children-and-Youth-Affairs.pdf [Accessed 25th August 2020].

House of Commons Education Committee (2011) Services for Young People, London: The Stationary Office.

IDYW (2014) In Defence of Youth Work Statement [online] Available at: http://indefenceofyouthwork.com/idyw-statement-2014/ [accessed 17th November 2020].

Jenkinson, H. (2013) ‘Youth Work a decade on’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies, 3(1), pp4-17.

Kiely, E. and Meade, R. (2018) Contemporary Irish Youth Work Policy And Practice: A Governmental Analysis, Child & Youth Services 39(1), pp17 – 42.

MacCarthaigh, M. (2015) Austerity and Reform of the Irish Public Administration. Revista de Administração e Emprego Público (RAEP) / Administration and Public Employment Review, 1(1), 143-164.

Madden, C. (2020) A brief exploration of the Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service’s (IGEES) outputs and its role in Department of Children and Youth Affairs policymaking, Administration, 68 (2), pp81–96.

McGimpsey, I. (2017) The new youth sector assemblage: reforming youth provision through a finance capital imaginary, Journal of Education Policy, 32(2), pp1–17.

McMahon, S. (2018) Governing Youth Work through Problems: A WPR Analysis of the Value for Money and Policy Review, Doctoral Dissertation for Maynooth University. Available https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338479497_Governing_Youth_Work_through_Problems_A_WPR_Analysis_of_the_Value_for_Money_and_Policy_Review_of_Youth_Programmes

McNeil, B., Reeder, N. and Rich, J. (2012) A framework of outcomes for young people, London: The Young Foundation.

Melaugh, B. (2015) Critical Conversations: Narratives of youth work practice in austerity Ireland, Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 7(1), 97-117.

Moullin, S., Reeder, N. and McNeil, B. (2011) Informing Investment in youth work: measuring value and strengthening the evidence base, London: Young Foundation.

NYCI (National Youth Council of Ireland) (2011) NYCI Pre-Budget Submission 2012: Real Needs& Essential Services, Dublin: NYCI.

NYCI (2020) Pre Budget Submission: Providing the Pathway [online] https://www.youth.ie/documents/nyci-pre-budget-submission-2021-providing-the-pathway/ [accessed on 18th November, 2020].

NYCI (2019) Submission to Minister Katherine Zappone T.D. On Youth Work Funding Levels 2005-2019 [online] file:///C:/Users/Sinead/Downloads/Submission-to-Minister-Katherine-Zappone-on-Youth-Work-Funding.pdf [accessed on 18th November, 2020].

O’Gorman, R. (2020) Youth Work Supports, Dáil Éireann Debate, Tuesday – 29 September 2020, Question 598 [online] accessed at: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2020-09-29/598/#pq_598 [accessed on 18th November, 2020].

Swirak, K. (2015) Problematising Advanced Liberal Youth Crime Prevention: The Impacts of Management Reforms on Irish Garda Youth Diversion Projects, Youth Justice, 1-19.

Swirak, K. (2018) A critical analysis of informal youth diversion policy in the Republic of Ireland, Youth & Policy [online] Available at: https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/youth-diversion-policy/ [accessed 23rd October, 2020].

Taylor, T., Connaughton, P., de St Croix, T., Davies, B., and Grace, P. (2019) ‘The Impact of Neoliberalism upon the Character and Purpose of English Youth Work and Beyond’ in Alldred, P., Cullen, F., Edwards, K. and Fusco, D. (eds) The Sage Handbook of Youth Work Practice, London: Sage pp 84-97.

Biography:

Sinead McMahon is a qualified youth worker and a lecturer in Social Policy at Limerick Institute of Technology.