Article: Becoming a Youth Worker: Contested approaches to education and training

This article discusses the assumptions, benefits, and limitations of three approaches to becoming a youth worker, namely: formal youth work education, as found in universities; competency-based non-formal youth work training, which combines on-the-job training, with off-the job skills development; and unstructured informal hands-on ‘learning by experience’.

Keywords: education; training; university; informal; formal; non-formal; youth work; youth development.

Introduction

Aspiring youth workers take different pathways to becoming a youth worker. This article discusses the assumptions, benefits, and limitations of: (1) formal youth work education, as developed in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs); (2) ‘non-formal’ competency-based youth work training, as provided through the Further Education sector and by employers in the UK, and by the Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector in Australia; and (3) informal unstructured workplace-based learning by experience. Each approach is analysed using Barnett and Coate’s curriculum framework. This article uses a reflective autoethnographic method (Anderson, 2006), and as this method requires, I have been a full member of the ‘social world’ I am studying, having experienced and delivered youth work education using each education/training approach, as a youth work learner, a youth work educator, and a youth work trainer and trainee. This discussion is relevant to contemporary debates about the place of youth work education in academia, pracademic approaches to youth work education, apprenticeship models of youth worker training, processes for recognition of prior learning gained through experience, transferable inter-professional skills, and articulation between competency-based and academic based approaches to youth work education. This discussion also documents some aspects of youth worker education history.

Definitions

Several terms require definition for the purposes of this discussion.

Informal youth work learning is defined as learning that occurs in an unstructured way, as learners work alongside more experienced youth workers. The learner learns through watching, through experimentation, through reflecting on mistakes, and through informal conversations with co-workers and supervisors. There is no formal assessment or certification of skills or knowledge.

Non-formal competency -based youth work training is defined as training that focuses on acquisition of demonstrable skills. In competency-based training, on-the-job learning is structured, follows a curriculum that specifies competencies and competencies are assessed by demonstration leading to formally recognised certification. Practical workplace-based learning is usually supplemented by classroom-based skills development. There are other types of non-formal outcomes-based programmes that are not competency-based. For example, structured youth work ‘probationary year’ programmes that included a programme of discussion and training sessions, with summative assessment at the end of the year; or, some youth work apprenticeship schemes, where there is a specified curriculum, but where outcomes and assessment is not specified in terms of discrete competencies. For reasons of brevity, these are not discussed in-depth in this article.

Higher Education-based formal youth work education is defined as youth work education that leads to a professionally recognised degree or postgraduate-level qualification in youth work or youth and community work.

Praxis: Many forms of youth work education and training discuss praxis, and Bradley, et al. (2024) contend that praxis is a distinguishing feature of the pedagogical framework for youth and community work education. They define praxis as a commitment to synthesis of theory and practice, (or ‘knowing’ and ‘doing’). Such a definition appears to be inclusive of both Freirian critical pedagogy, which uses critical dialogical conversation to support learners (and teachers) to achieve and refine this synthesis (Jeffs & Smith, 2005) and of forms of social pedagogy which draw upon multiple bodies of theory (Slovenko & Thompson, 2016) for the same purpose.

Theory

I have found two bodies of theory are useful when trying to make sense of the strengths and limitations of different approaches to youth work education and how these might be resolved. The first theory is Barnett and Coate’s curriculum framework, which conceptually differentiates various types of learning, which they call ‘knowing’, ‘acting’, and ‘being/becoming’. ‘Knowing’ and ‘acting’ are familiar types of learning. Knowing includes conceptual and informational learning, including learning about ethics and value systems. ‘Acting’ includes skills, and ‘knowing how to’ do things. ‘Becoming’ requires embodiment. This includes the embodiment of values, of judgement, and the embodied integrations of ‘knowing about’ and ‘acting’. In contemporary education systems where the focus is on ‘demonstrable’ assessment, ‘becoming’ is considered problematic because it is not readily demonstrable. ‘Becoming’ is sometimes implicit (as in discussion of ‘developing judgement’) but is rarely explicitly discussed. Barnett and Coate’s curriculum framework is useful as a tool for analysing youth work education because it accords with the holistic aspirations of youth work education. The underlying assumptions Barnett & Coate make about education are congruent with youth work assumptions and values (Cooper et al., 2014). The second body of work I have found useful is Posner’s (2009) proposals for pracademia, in which he contends that greater engagement between universities and practitioners is vital to the well-being of both universities and professional practice. Posner offers suggestions about how this might be achieved and his work suggests possible ways forward to resolve some limitations of the various approaches to youth work education.

Method

At the beginning of each section, I describe my experience of each approach to youth work education. I reflect upon the strengths and limitations of each approach as a learning method, and analyse my observations using Barnett and Coate’s (2005) curriculum framework. I adopt a critical approach to analysis of strengths and limitations of each method, attempting to be dispassionate in my description and even-handed in my analysis.

Informal youth work learning

My first experience of learning to become a youth worker was through informal learning. Initially as a volunteer and later as a paid part-time youth worker, I worked alongside other youth workers, in youth clubs, residential youth work, and doing outreach work on the Isle of Wight and in Lancashire. Most of my colleagues were more experienced and many were formally trained. Mentoring and learning occurred after each session, as we were cleaning up, or in the pub at the end of the night, where we would reflect on what had occurred, and what we might have done differently. My mentors included Gina Ingram and Sue Bloxham, who both encouraged reflection and experimentation. My informal learning about youth work continued through self-education as I moved into teaching youth work and continues now through reading, research, and observation.

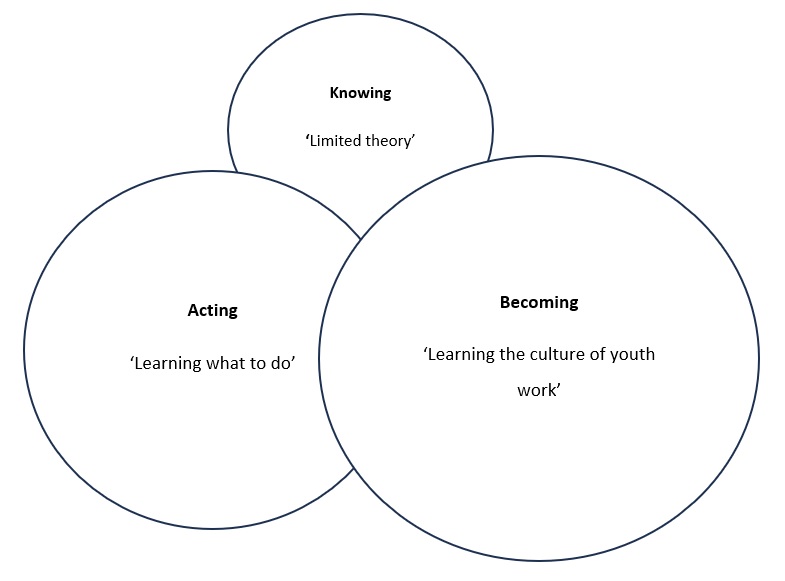

In terms of Barnett and Coate’s curriculum framework, the focus of informal learning was primarily on learning how to become a youth worker, and learning from experience what to do in situations as they arose, as represented in Figure 1. The emphasis of this approach was on learning what to do in familiar situations that occurred in the particular context of youth work. This emphasis meant that in terms of Barnett and Coate’s framework, most of the learning was about what to do (action/acting) within the culture of a specific youth work setting (becoming a youth worker). An important part of this informal learning was learning how to fit into the practice of each group of youth workers. As a volunteer and part-time youth worker, I worked in a variety of contexts (rural, urban, detached, centre-based, activity oriented etc) that reflected different youth work ‘cultures’. A commonality was that there was little emphasis on theory. Although Sue and Gina sometimes referenced their practice to theory, the majority of youth workers operated pragmatically, and a few were actively hostile to any theorisation. There was no suggestion that reading might be useful, reflecting perhaps the limited youth work texts available at the time. The formal part-time (Bessey) training was not considered useful. Figure 1, uses Barnett and Coate’s framework to represent the curriculum balance in informal youth work learning, as I experienced it. The relative sizes of the circles represent the relative emphasis upon each type of learning.

Figure 1: Informal education

Reflecting on my experience, my learning was embedded in the contexts in which I was working, and learning took place over an extended period. I was fortunate to have some skilful, thoughtful, and generous colleagues. A strength of this approach is that, if the practices of the experienced youth work mentors are sound, and the experiences are diverse, and the learner is receptive, this approach enables the transmission of experience, and can be inclusive of youth workers who do not have the opportunity to study youth work formally. A limitation is that learning is embedded in a specific context and youth workers may not develop comprehensive youth work skills. Embedded practice means that skills are often tacit, which may mean that skilled youth workers are not able to articulate why things are done in particular ways or recognise the skills they have. Finally, the learning of novice youth workers relies on the quality of practice of the experienced youth workers who teach them. If the practice of the experienced workers is problematic, learners may replicate poor practice.

Non-formal competency-based youth work training

Whilst working in Lancashire (1983-1987), I gained experience as a non-formal youth work trainer working alongside Bill Taylor and John Cowgill and others. We developed and then delivered a competency-based, part-time youth worker training course to replace the inputs-focused ‘Bessey Basic[1]’ training course. We believed this was one of the earliest competency-based youth work training in the UK. The brief was to provide an experiential course that did not require literacy skills and would support part-time youth workers to gain specific skills. Learning followed a curriculum that was devised to provide skills needed at different stages of a youth worker’s development. The ‘introductory’ course taught basic skills for working with young people. The ‘worker-in-charge’ course taught staff management skills. Whilst all competency-based training is outcomes focussed, not all outcomes focused training uses a competency framework. Competency-based training focuses on development of demonstrable skills. After this, I worked with Kate Clements at the Lancashire Girls Work Unit (1987-1989) on experiential courses to develop skills of volunteers and full-time and part-time youth workers in working with girls and young women. These courses were experiential and outcomes-focused (to change in the way youth workers worked with girls and young women), but did not work within a competency framework (did not seek to develop specific ‘girls work’ youth work skills).

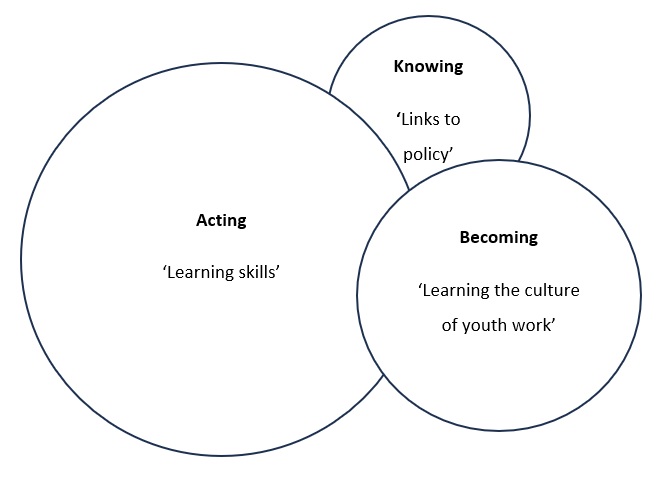

In terms of Barnett and Coate’s curriculum framework, the focus of competency-based learning was primarily on learning specific skills and practising them in the workplace, as represented in Figure 2, As before, the relative emphasis is represented by different sized circles. Within competency-based training, explanations about why things should be done in a particular way were referenced to policies, or discussed pragmatically (‘it’s better this way’) and only occasionally referenced theory. ‘Knowing’ in Barnett & Coate’s framework, therefore focused upon knowing what the policy said, rather than gaining a theoretical understanding of the options and considerations.

Figure 2: Non-formal competency-based youth work education

Reflecting on this experience, the strengths of the competency approach are that it is well-suited to the development of youth work skills that can be demonstrated and performed. It was also potentially suited to extending skills of youth workers who had already gained understanding of youth work, as for example in the work of the Girls Work Unit. Limitations are that, as a sole method of training, competency-based training omits important skills that do not fit into the competency approach (for example the use of judgement in complex situations). As was argued by Durkin and Davies (1991) at the time, it was impossible to encompass all youth work education requirements in lists of demonstrable ‘competencies’. Focus on action leads to a neglect of the foundational knowledge base for youth work, and emphasises ‘rules and recipes’ for what should be done (what should I do if this happens?) rather than a deeper engagement with values and ethics (what is the overall value-base and purpose of this work, and how can this be achieved best). Skills lists are reductionist, which leads to over-simplification of the youth work role and deskilling (Corney & Broadbent, 2007). If combined with genericization of courses, Corney and Broadbent (2007) contend this may lead to loss of youth work as a distinct form of practice. Additionally, once someone is assessed as ‘competent’, this may promote the erroneous belief that further skill and knowledge development is unnecessary.

Formal youth work education

I have worked as a youth work academic in the HE system in the UK and Australia, since 1987. At St Martin’s College (1987-1991) I was involved in teaching the ‘apprenticeship’ youth and community work training programme, led by Pravin Patel, which combined on-the-job learning with classroom-based teaching. At St Martin’s and at Edith Cowan University, I have taught on degree or postgraduate programmes leading to professional qualifications in youth work. Formal learning in higher education follows a highly structured curriculum devised to prepare graduates for long-term careers in a variety of youth work roles. There are some differences of emphasis between the university curriculum for youth work in the UK and in Australia, especially in the duration of placements and the theoretical foci. Possibly in response to my reflections on informal and non-formal youth work education, my major teaching and research interests for the last 30 years have been youth work theory (Cooper, 2012, 2018a; Cooper & White, 1994), and how to combine benefits of formal and informal education in youth work education (Cooper & Brooker, 2019; Cooper, 2017, 2019; Cooper et al., 2014; Cooper & Scriven, 2017).

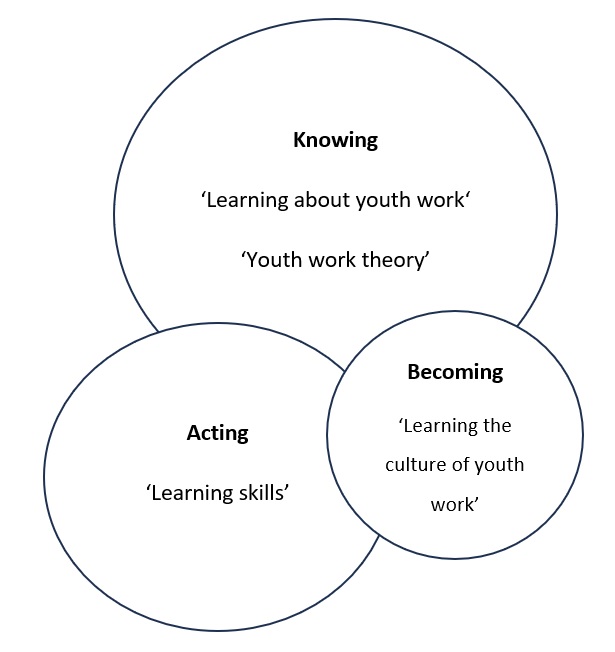

In terms of Barnett and Coate’s curriculum framework, formal youth work education focuses upon learning about youth work, learning about youth work skills, and learning about underlying theoretical orientations, presented in classrooms or online, and then practised during placement, as represented in Figure 3, where the circle sizes reflect the relative emphasis. Explanations about why things should be done in a particular way are referenced to theories, and policies are approached critically. Whilst aspects of youth work culture are taught, students’ exposure to youth work culture may be limited to their supervised placement.

Figure 3: Formal youth work education

Reflecting on this experience, a strength of formal youth work education is that it makes explicit the practices of youth workers, offers theoretical explanations, facilitates development of knowledge about youth work as a discipline, and offers explanations of professional boundaries. Some limitations of formal youth work education are that experience of practice rests heavily upon the quality of the placement experience, and that the university environment generally privileges theory-knowledge over practice-knowledge. The values and structures of neo-liberal university systems require a prescriptive approach to curriculum that limits flexibility to respond to specific needs of student cohorts. Staff experience ‘role strain[2]’ because of incongruencies between university values and the values of the youth work field (Cooper & Brooker, 2019). The conflicts between values causes tensions in many areas, for example, with staff appointments, youth work educators often value practice experience and professional qualifications, while university administrators often prioritise academic qualifications and research. Additionally, Australian youth work degree programmes, like other professional programmes, have been under pressure to include more generic teaching, shared with other disciplines (Cooper, 2018b) and this further limits the capacity of youth work courses to maintain relevance and integration. Generic teaching limits opportunities to integrate youth work theory and practice and makes it more difficult for students to gain an understanding of the culture of youth work and how skills are applied in the context of youth work practice.

In both UK and Australian university systems, youth work courses have been under pressure to survive. Structural factors lead to a dilemma. If youth work degrees maintain their responsiveness to students and the profession, including the centrality of their connection with practice, youth work programmes may become marginalised within universities. This may trigger the closure of the youth work programme, as has occurred in both the UK and in Australia. Alternatively, if youth work programmes align with dominant values within higher education, they risk losing touch with practice, especially if there is an over-use of generic content and/or academic staff do not have youth work practice experience.

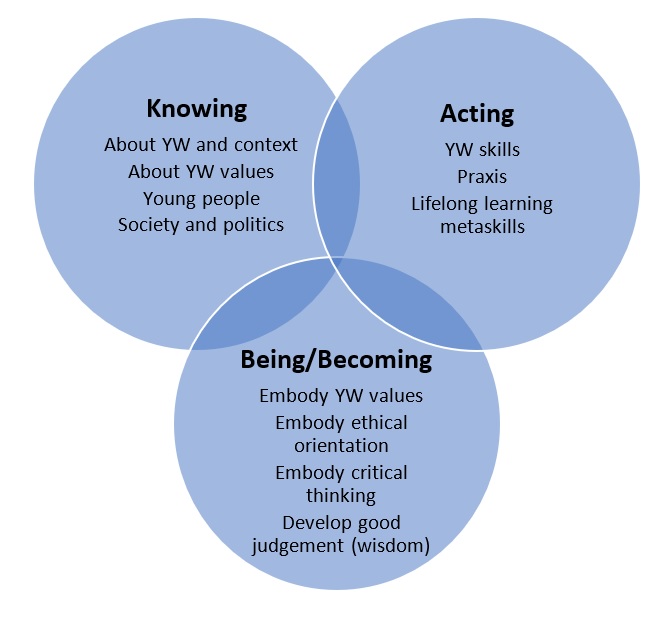

Towards wisdom: holistic pracademic youth work education

The development of wisdom used to be the primary goal of universities, and internationally, can still be found in many of their mottos. Holistic education seeks to prepare students to become people who use knowledge, skills and judgement to act wisely in the world, and this aligns with the goal of developing wisdom. Applying Barnett and Coate’s (2005) holistic curriculum framework, from my analysis, I contend it would be desirable for youth work education to aspire to integrate ‘knowing’, ‘acting’ and ‘being/becoming’, in roughly equal measure in youth worker education. This applies whether learning occurs formally, non-formally or through mentored informal learning activities. The goal of youth work education thus becomes to enable students to gain, by whatever means, the knowledge, skills and judgement to respond skillfully and wisely to whatever youth work situation arises.

If this is accepted, all youth work education/training, whether formal, non-formal and informal education should seek ways to facilitate acquisition of knowledge and theory relevant to youth work, and should provide supported opportunities to develop and hone youth work practice skills. In addition, all youth work education systems should facilitate learning that enable students to embody youth work values and ethics, and integrate their knowledge and skills to develop their judgement about when and how to intervene based upon sound judgement informed by knowledge and skills. These goals mean that education programmes are not finished when a certificate is awarded, because learning is never complete. Therefore, students need to acquire the metaskills to become self-directed life-long learners and mentors for others (Cooper et al., 2014) who are able to learn equally from experience, from observation, and from formal study.

Figure 4: Towards wisdom: holistic youth work education

In figure 4, the domains of ‘knowing’, ‘acting’ and ‘being/becoming’ are depicted as being the same size, to emphasise that holistic youth work education requires development of each aspect of this schema in equal measure. The circles are interconnected to emphasise the necessity for integration between knowing acting and becoming.

By this argument, holistic learning requires a particular kind of life-long learning, and requires teaching, by whatever means, some key meta-skills, namely:

- Learning to learn from life and books: by doing, observing, practising, reading, analysing, discussing, and reflecting to integrate and embody knowledge, skill, and judgement. This means raising questions with students about the purposes and methods of education. It also means supporting students to gain the necessary metaskills to use all methods of learning.

- Reflective practice: these skills must be taught. It should not be assumed that all students know how to do this, or understand how this relates to learning or why this is important.

- Analysis and critical thinking: component skills and methods should be taught, contextualised in the youth work curriculum, and the value of these skills discussed.

- Pracademic youth work (praxis): must be demonstrated in teaching so that applications of theories are taught and related to practice examples, and practice skills are contextualised with theory, values, and ethics in ways that enable students to embody their learning. This is an argument against the usefulness of generic teaching shared with other professions.

- Developing judgement: as part of a lifelong journey towards wisdom, we should ask students to consider how knowledge and values inform judgement about right action, and what this means for them.

Holistic youth work education, praxis and pracademia

To overcome the limitations of each approach to learning, each approach requires some supplementation to achieve the synthesis of theory and practice, which is embodied in judgement and right action.

Informal youth work learning: holistic pracademic youth work education requires informal learning to be supplemented with learning that strengthens the capacity to make tacit learning explicit and to draw upon theory, where useful. This may mean reading about youth work practice in other contexts and discussing how practice relates to youth work theory to gain a broader understanding of the diversity of youth work beyond specific contexts. The requirement to explicate practice clearly is important because it enables youth workers to communicate effectively about their achievements, about how youth work goals and methods different from other professions, and about the specific situational supports needed for successful youth work. A pracademic approach (Posner, 2009) could facilitate this by linking universities with practitioners, and by academics working with practitioners to explicate and theorise tacit practice, so it can be shared more readily, and to collaborate to translate research into practice.

Competency-based (non-formal) youth work training: holistic pracademic youth work education in this context requires competency-based youth work education to be supplemented with a commitment to lifelong learning (rather than just ‘becoming competent’). Support is needed to develop critical thinking that includes theoretical understanding and encouragement of reflection on values, contextual judgement and identity. This will enable students to learn from their practice how to adapt methods to changing circumstances and how to develop higher order skills necessary for practice, possibly, post-qualification. Within current structures, this learning depends upon individual commitment and the capacity of mentors to inspire curiosity about links between theory and practice. Youth workers need to be able to develop and adapt their practices to changing contexts, whilst maintaining what is essential to youth work. Competency-based training teaches a fixed skill-set, which does not provide the theoretical basis from which to adapt the methods and priorities of youth work, whilst maintaining the essence. As with informal learning, pracademic connections between universities and practitioners, and engagement of practitioners as collaborators in research could facilitate development of aspects of learning that are not emphasised in competency-based training.

University-based courses: holistic pracademic youth work education in this context requires formal youth work education to continually strengthen connections with practice, to ensure active steps are taken to maintain the relevance of what is taught. This can be achieved by fostering a reflexive relationship between theory and practice knowledge through strong field connections so that teaching and research becomes informed by practice. If universities committed to a pracademic approach (Posner, 2009) to youth work, this would require development of education and research programmes that engage fully with youth work practitioners. Such a commitment would have implications beyond curriculum, for staff recruitment and for enabling the appointment of staff who work simultaneously within universities and as professional youth workers. These recommendations do not resolve tensions between some university structures and systems and pracademic education models. These tensions would still have to be managed locally, as well as they can be. If these tensions cannot be resolved, and university youth work courses are lost (or lose their focus on youth work), the youth work field will be diminished.

Conclusions

There are many ways to educate, train or learn to be a youth worker. This analysis illustrates that each education/training approach has some strengths and some limitations. All approaches work, to some extent and for some people, but no approach develops all aspects of youth work learning necessary for a rounded education in youth work. Instead, each approach provides a starting point that requires different kinds of subsequent supplementation. Any recognition of prior learning, should consider how the learning was gained and what aspects of prior learning may need supplementation.

Youth work education would be enriched if all youth work educators aimed to support students to develop wisdom through holistic learning. Every student would learn, to the greatest extent possible, the skills, knowledge, judgement, and humanity needed for youth work, and for life. Within a holistic framework, all approaches to youth work education have a place, but for holistic learning, active steps must be taken to overcome limitations of each approach. Many other forms of professional education where graduates work with people, would also benefit from more holistic approaches to curriculum and learning, appropriate to their context.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 23 July 2024

Footnotes:

[1] The ‘Bessey Basic’ training course was a part-time youth worker training course offered throughout the 1960s, 1970s and into the early 1980s. It was introduced in response to the 1962 Bessey Report on the Training of Part-time Youth Workers (no primary source found). Training had a suggested curriculum and was offered across England and Wales. Training was ‘inputs’ based and consisted of a series of lectures to complement workplace-based practical work. The training courses were organised by the local authority County Youth Training Officers in partnership with voluntary organisations, and formal training providers. The content and duration varied between Local Education Authorities. More information is available in the 1965 Second Report on Training of Part Time Youth Leaders and Assistants available https://www.youthworkwales.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/second-report-training-1.pdf

[2] Role strain occurs when people are faced with trying to satisfy the demands imposed by incompatible expectations. In this case, for example, universities require curriculum to be specified in advance, whereas applying youth work principles, curriculum would be at least partially emergent, in response to the differing needs of particular groups of students, and emerging teaching opportunities.

Acknowledgements:

This article expands upon ideas I presented as a SALTO keynote presentation on ‘Becoming a youth worker’ delivered online in Estonia in November 2022. The brief was to examine youth work education from a perspective of ‘being and becoming’ rather than ‘doing’ and to transcend binary thinking about youth work education as either formal education or non-formal training. This article also draws upon my presentation to the 2022 PALYCW conference entitled ‘Pracademic youth work education and systemic impediments in neoliberal universities: resistance, mitigation, and change’

References:

Anderson, L. (2006). Analytic Autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373-395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605280449

Barnett, R., & Coate, K. (2005). Engaging the Curriculum in Higher Education. Open University Press and McGraw Hill Education.

Bradley, C., Devlin, M., Brennan, P., Tierney, H., Reynolds Conlon, S., & Crickley, A. (2024). Pedagogy as Praxis: Education and training in initial professional education for Community Workers and Youth Workers. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 21(1-2). https://doi.org/10.1921/jpts.v21i1-2.2050

Cooper, T. (2012). Models of youth work: a framework for positive sceptical reflection. Youth and Policy, 109, 99-117. https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/cooper_models_of_youth_work.pdf

Cooper, T. (2017). Curriculum renewal: Barriers to successful curriculum change and suggestions for improvement. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 5(11), 115-128. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v5i11.2737

Cooper, T. (2018a). Defining youth work: exploring the boundaries, continuity and diversity of youth work practice. In Pam Alldred, Fin Cullen, Kathy Edwards, & Dana Fusco (Eds.), SAGE Handbook of Youth Work Practice (pp. 3-17). Sage.

Cooper, T. (2018b, July 2nd to 5th). Student choice and skill shortages: Some effects of demand-driven funding. Research and Development in Higher Education: [Re] Valuing Higher Education, Adelaide.

Cooper, T. (2019). Calling out ‘alternative facts’: Curriculum to develop students’ capacity to engage critically with contradictory sources. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(3), 444-459. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1566220

Cooper, T., Bessant, J., Broadbent, R., Couch, J., & Edwards, K. (2014). Australian youth work education: Curriculum renewal and a model for sustainability for niche professions. https://ltr.edu.au/resources/PP10_1612_Cooper_Report_2014.pdf

Cooper, T., & Brooker, M. R. (2019). Achieving economic sustainability for niche social profession courses in the Australian higher education sector. https://ltr.edu.au/resources/FS16-0260_Cooper_FinalReport_2019.pdf

Cooper, T., & Scriven, R. (2017). Communities of inquiry in curriculum approach to online learning: Strengths and limitations in context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(4), 22-37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3026

Cooper, T., & White, R. (1994). Models of youth work intervention. Youth Studies Australia, 13(4), 30-35.

Corney, T., & Broadbent, R. (2007). Youth Work Training Package Review: More of the Same or Radical. Youth Studies Australia, 26(3), 36-43.

Durkin, M., & Davies, B. (1991). “‘Skill’, ‘competence’ and ‘competences’ in Youth and Community Work”. Youth & Policy(September).

Jeffs, T., & Smith, M. K. (2005). Informal Education: Conversation, Democracy and Learning. Educational Heretics Press.

Posner, P. L. (2009). The Pracademic: An Agenda for Re-Engaging Practitioners and Academics. Public Budgeting & Finance, 29(1), 12-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5850.2009.00921.x

Slovenko, K., & Thompson, N. (2016). Social pedagogy, informal education and ethical youth work practice. Ethics and Social Welfare, 10(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2015.1106005

Biography:

Trudi Cooper is an Associate Professor in youth work at Edith Cowan University, Australia where she is a member of the Centre for People, Place and Planet. Her research includes youth work education, youth work theory, and ecopedagogy. She is an Australian Learning and Teaching Fellow, and a member of the International Federation of National Teaching Fellows. Previously, she was a youth worker, youth work educator and youth work volunteer in the UK.