Article: Addressing Serious Male Youth Violence: Missed opportunities within the UK Serious Youth Violence Strategy

In this article, Colm Walsh responds to the Serious Youth Violence Strategy published earlier this year. Colm presents an interesting and evocative view that serious violence in the community is a male issue, arguing that a gender conscious and trauma informed approach should be integrated into policy if practice is to be truly informed.

Violence is a global concern and exposure to violence during adolescence is in excess of 90% (Richter et al, 2018). However, it is not yet well established in international population based studies just how prevalent it is amongst young men. We know that the majority of perpetrators of violent crime in the UK are male (ONS, 2018) and overwhelmingly, males are attacked by other males (Jackson et al, 2016). In Northern Ireland, young men were more likely to be convicted of troubles related to violent crime in what was generally regarded as Europe’s longest running conflict (Lynch & Joyce, 2018). Across the life course many young men who experience trauma (such as violence) during adolescence are more likely to engage in serious violence as they develop. Across 164 countries, 96% of the prison population are male and many of these men have histories of violence (Muncie, 2009). In my own work with boys and young men, 90% of them report having experience of violence with more than three quarters indicating frequent exposure to interpersonal violence.

…it’s a way to deal with things-you know. Fighting is something that just happens. It’s part of everyday life and it’s not too bad most of the time. (Young man aged 16)

Whilst acknowledging ‘being male’ as a primary risk factor, UK governments have not actively developed polices nor implemented strategies which help us to understand or address why this is the case or identify what to do about it (Brown & Burton, 2010). In recognition of the increase in more serious forms of violence amongst a younger population and primarily between young men, the UK government recently published a strategy to address serious youth violence (Home Office, 2018). The strategy outlines recent trends in youth violence, drivers of serious violence and 19 commitments to mitigate the risks of violence amongst young people.

This article is a critique of the Serious Youth Violence Strategy (Home Office, 2018) and includes recommendations for consideration in future violence prevention strategies which place more emphasis on the role of masculinity in the lives of young men and the perpetration of violence. The data presented in the article is informed by fifteen years of practice and research with more than 1000 boys and young men around the theme of gender, trauma and violence.

The scale of the problem: Reality of violence, costs and impact

Violence is a pervasive problem (Krauss, 2006) and is the second leading cause of death for 15 – 19 year olds (UNICEF, 2017) with up to 500 young people dying each day as a result of violence (Baxendale et al, 2017). In addition to fatalities, there are many more non-fatal altercations by up to ten times (Mikhail & Nemeth, 2015). Violence is also a costly problem. Excluding armed conflict, it costs almost £30bn annually with implications for the individual, families, the community and wider societal public services (Bellis et al, 2012). Despite some figures suggesting that UK incidents of violence have steadily reduced since the 1990’s hospital figures suggest a steady rise in serious violence since 2014/15 (ONS, 2018). Violent crime such as homicides, knife crime and gun crime has risen considerably since 2014. Police statistics reveal that violent crime has increased by 94% between 2012 and 2017, whilst knife crime has risen by more than one third and gun crime by just under one third (Home Office, 2018). Latest police figures for England show that there were 1.2 million incidents of violence during 2017, the first time that the figure exceeded 1 million (ONS, 2018).

Understanding youth violence

Understanding the drivers of serious youth violence is important. If the drivers are understood, and defined clearly, responses are potentially more effective. The Strategy points to overwhelming evidence that ‘males commit the majority of serious violence’ (Home Office, 2018:39) and yet gender is not referenced anywhere as either a driver or a risk factor. Indeed, there are less than twenty individual references to boys or men throughout the 111 page document. As a result, responses to understand and address this from a gender perspective are missing. Why is this important? Gender, and in particular masculinity are one of the greatest social realities for young men (Harland & McCready, 2015). Hyper masculine beliefs appear to enable males to justify violence on the grounds of demonstrating their identity, attaining status in a group and/or protect themselves from a perceived threat.

You can’t let someone look at you or threaten you or say something about your family and get away with it…What would happen? If you didn’t do anything you’d look weak and ten more of them would be on your back the next time (Young man aged 14)

Despite being a constant predictor of aggressive attitudes gender is an area of young men’s lives that has been consistently overlooked in violence research, policy and practice (Sundaram, 2013). To date, studies have focused on men’s role as either the victim of violence or the perpetrator of violence against women (Dagirmanjian et al, 2016).

There is a difference. Girls will be all quiet and go behind the back but fellas just go head first and start punching-it’s easier that way though. Things get dealt with quicker. (Young man aged 18)

Priority areas

Instead, this Strategy focuses on other drivers, which themselves are important but provide only a partial picture of the causes of serious youth violence. Both the Serious Youth Violence Strategy (Home Office, 2018) and the Home Office ‘refreshed’ strategy (Home Office, 2016) to respond to gang violence and exploitation targeted the use of substances and the contribution which the transport of drugs had across County Lines to serious violence. This particular driver is an issue for the young men in my own practice.

Drugs is just one of those things-it’s there and because you see it all the time it’s accepted so you don’t see it as a crime. You see it as bad but not really as a crime. (Young man aged 14)

Although it has been well established that both alcohol are drugs are often antecedents of violence, it is less clear whether the use of substances are correlational or causal. At best the evidence is suggestive rather than conclusive (Boles & Miotto, 2003). One of the challenges is that studies into aggression and associations with substances have primarily focused on specific types of substances with few exploring the impact of substance use in younger people (Tomlinson, Brown & Hoaken, 2016). Whilst there is no statistically significant difference between consumption of substances between genders, there are differences in relation to behavioural responses following consumption, creating further questions around the role that substances play in the perpetration of male youth violence.

…yeah you do see girls being pissed and getting angry. But they mostly just slabber. There not going to get into a serious fight. It usually gets broke up quicker too. If we got into bother though on a night out it could turn into a brawl. You know what I mean? There is a difference. (Young man aged 18)

What the Strategy does clearly state is that approaches to prevent alcohol and drug fuelled violence need to involve wraparound and early intervention approaches. These approaches have been accepted in UK prevention policy for two decades.

Policy changes since the 1990s reflect a shift in focus from isolated working and towards whole family and integrated services (Malin et al, 2014) with emphasis on prevention as well as early intervention. The focus became on systematically understanding risks, where they present and for whom. The Strategy outlines a commitment to early intervention using well established universal and targeted interventions. Universal approaches help to ensure that young people have positive opportunities, are able to develop their own thinking and social skills and are engaged in safe and supportive environments with the presence of positive role models to support them to achieve their potential. Targeted interventions are aimed at young people perceived to be ‘hard to reach’ or ‘at risk’ due to a range of factors.

Whilst intuitively appealing, early intervention approaches are only as effective as the evidence they are based on, the intervention being implementation (and for what purpose) and the competency of the staff who are delivering the intervention. One difficulty is that the current evidence, which is largely based on systematic reviews of interventions that target aggression rather than serious youth violence, is overwhelmingly related to US research. Furthermore, a significant proportion of these findings are derived from studies that focus on early childhood rather than youth interventions. Therefore, inferences around outcomes are limited. From the little evidence that is available, data has shown that changes in knowledge and attitudes do not necessarily equate to behavioural changes (Gielen et al, 2006) and broadly, universal prevention approaches such as information sharing between agencies and awareness raising with young people are largely ineffective in reducing youth violence (Mikhail & Nemeth, 2015). In my own practice, there have been relatively few outcomes sustained from awareness raising activities alone. Young men who engage in violence prevention programmes go back into their own lives and the communities that help shape their behaviours. Very often, cognitive changes do not result in behavioural changes because the environment is not conducive to behavioural change. In other words, perpetrators may think differently but lack the skills to implement behavioural change (Harland & McCready, 2015). However, when awareness raising (through cognitive and reflective practice) is combined with skills development in real world settings more is achieved and the earlier that this combined approach is facilitated, the better the outcomes may be (Early Intervention Foundation, 2015).

Family support underpins much of the early intervention discourse. It’s a familiar but contested concept (Devaney & Dolan, 2014) which varies according to context, purpose and underpinning values within specific models (Churchill & Sen, 2016). There is no doubt that some families experience significant adversity and if they can be appropriately supported, outcomes may be improved. But how outcomes are defined vary (Flint et al, 2011) and one of the difficulties of family support in the context of violence prevention is that whilst there has been significant focus on family characteristics as predictors of violence, a meta-analysis of 119 longitudinal studies found only moderate correlations between family characteristic and the perpetration of youth violence (Proctor et al, 2009). These findings suggest that whilst family characteristics are important, other factors are needed to produce violent behaviour (Derzon, 2010). Therefore, the evidence that investing in family support (to reduce youth violence) is limited – at least in the absence of a more coherent framework which addresses other mediators and moderators of violence. In my own practice, engaging young men whose families were being supported by multidisciplinary and intensive support teams, it was evident that rather than family circumstances driving their violent behaviour, it was the normalisation of violence. In the communities which many young men live in, traditional concepts of manhood such as defender, protector and provider become toxic and reinforce the legitimisation of violent behaviours. That is not to say that increasing protective factors is not worthwhile. Childhood maltreatment, exposure to community violence and other adverse childhood experiences have become widely integrated into prevention policy. This focus provides real opportunities for families to engage in preventive work underpinned by robust evidence (Violence Policy Center, 2017) and family environments may be the best places to mitigate these risks (Tighe et al, 2012)

The Serious Violence Strategy does build upon increasing evidence that Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) and exposure to trauma has a cumulative and detrimental impact on young people and underpins the rationale behind some strategies being used in some public services (such as the police force) to inform practice. This is welcomed but misses the nuances within trauma research and in particular the association between trauma and violence. For instance, there are established (but not well understood) gender differences in trauma exposure and the perpetration of violence. Four decades of data suggest that there is an association between trauma exposure and violence amongst young men but the association is not as strong with young women (Falshaw et al, 1996). We know that following trauma exposure young men and young women respond differently, both cognitively and behaviourally with young women more likely to present with PTSD symptomatology (Aebi et al, 2017). Whilst there have been some advances in the screening for and treatment of PTSD, in the context of violence prevention the focus on mental health disorders such as PTSD is of limited value. The symptom clusters assessed for only partially evidence the significant externalising difficulties experienced following trauma (van der Kolk, 2005) and therefore the relationship between trauma and aggression is misunderstood. What appears to be instrumental aggression may still actually be reactive and trauma related (Ruchkin et al, 2007; Finkelhor et al, 2000) despite few other symptoms on measures that screen for conditions such as PTSD. Rage and aggression can mask the distress that young men experience (Seaton, 2007). Trauma exposure creates aggressive pathways through hyper-arousal, hyper-vigilance and inappropriate hostile reactions (Maschi & Bradley, 2008). I have seen this throughout my career with many young men engaged with both care and justice services and who present with behavioural difficulties. However their histories illuminate the causes of such aggression. Many are witness to domestic abuse, to high levels of violence in the community and to neglect. In their study of twenty violent offenders in a South African Prison, Matthews et al (2011) found that many of the men’s histories were of maltreatment and victimisation and in an Australian study of adult male prisoners, Hasley (2018) found that the majority of crimes committed could be considered in the context of externalisation difficulties experienced following childhood trauma. Although several trauma informed initiatives are referred to in this Strategy, trauma responsive interventions, which take account of gender differences that may mediate exposure and perpetration are missing. Across cultures, gender constructions (such as hegemonic masculinity) may help to explain why boys who have been exposed to trauma have a higher risk of acting violently and a more concrete focus in this area could advance policy and practice (Aebi et al, 2017).

The lack of evidence

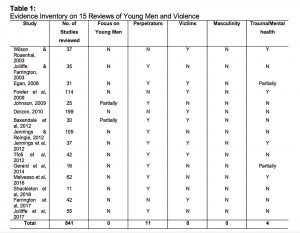

The absence of a gender conscious and trauma informed focus stems, at least in part, from a lack of studies having taken place to explore this association. An evidence inventory of systematic reviews, meta-analysis and other reviews was undertaken in July 2018 and found only fifteen studies or reviews focused on gender and/or trauma in relation to youth violence. From these, no study focused exclusively on young men or masculinity in relation to violence and only a minority (n=4) explored the role of trauma and/or mental health issues in relation to violence (Table. 1.).

A search for UK based prevalence studies related to young men and violence was undertaken and no results were found. Additionally, a search across 3737 clinical trials related to gender, trauma and violence yielded no results. This omission is not unique across policy and research. As well as the neglect of gender and trauma issues in the Serious Youth Violence Strategy, they are also neglected in other related policy documents. The Ending Violence Against Women And Girls Strategy (EVWG) 2016 – 2020 refers to addressing social norms but contains no detail on the role of males in perpetrating violence (Home Office, 2016). In Northern Ireland, whilst the Department of Justice’s strategic framework to increase community safety refers to the social determinants of offending, there is no reference to gender as a consistently strong predictor nor indicators to respond to this evidence (DOJNI, 2012).

Conclusion and recommendations

The Serious Youth Violence Strategy is comprehensive and builds upon commonly accepted risk factors associated with violence. However, the Strategy was an opportunity to take full advantage of the public health approach to violence and orientate policy makers and practitioners towards a gender conscious approach. Whilst there are some references to tackling social norms that sustain violence, even here there is no acknowledgment of the central role that males play in the perpetration of violence and the reasons why this may be the case (Home Office, 2016a).

One reason may be because there is a dearth of data on young men’s experiences of violence both as victim and perpetrator (Richter et al, 2018). We know little about how young violent men make sense of their worlds and even less about how to effectively engage them in prevention. What we do know is that violence is an integral and complex aspect of male identity (Harland, 2011). From an early age, boys are conditioned to behave and act a certain way that is different to girls and socialised into expectations of behaviour (Crooks et al, 2007). While each masculinity measure is unique, hyper-masculinity refers to cognitive distortions males have about what it means to be male, how they should engage with the world and how they should respond to social stimuli (Brown & Burton, 2010). The presence of masculine beliefs amongst males who engage in violence is a salient issue under addressed in this Strategy. The presence of trauma may exacerbate these cognitions and impact on behavioural responses. More research is needed exploring the role of violence in young men’s lives.

It is well established that young men involved in justice are significantly more likely to have experienced traumatic incidents. However, it is not clear under what circumstances, and through what developmental processes does trauma lead to violence (Allwood & Bell, 2008; Kerig, 2012). There is some evidence that screening is necessary at an earlier stage and in a universal way. This, however, begs the question, what interventions or supports are then implemented to both engage with and support young men with the skills and strategies they need to respond to their trauma and navigate difficult and complex social relations? Research that helps practitioners, researchers and policy makers understand the mediating and moderating pathways that link trauma to violent offending has important implications (Maschi & Bradley, 2008) and more work is needed here to inform future violence prevention strategies.

Acknowledging and addressing the distinct needs of males and females should become an integral part of violence prevention efforts, and additional research and funding mechanisms to enhance gender responsiveness are needed.

The lack of practitioner access to high quality evidence as well as a lack of awareness of effective violence prevention models is a real concern and one which prevents meaningful progress (Mikhail & Nemeth, 2015). More work is needed to help practitioners access reliable evidence and also to test and robustly evaluate gender conscious models of practice which both engage young men and equip them with feasible alternatives (cognitive and behavioural) to violence.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 10 October 2018

References:

Aebi, M., Mohler-Kuo, M., Barra, S., Schnyder, U., Maier, T., and Landolt, M.A. (2017) Post traumatic stress and youth violence perpetration: A population based cross sectional study. European Psychiatry, 40, 88-95.

Allwood, M. A. and Bell, D. J. (2008) A preliminary examination of emotional and cognitive mediators in the relations between violence exposure and violent behaviors in youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(8), 989-1007.

Baxendale, S., Cross, D., Johnston, R. (2012) A review of the evidence on the relationship between gender and adolescents’ involvement in violent behaviour. Aggression and violent behaviour, 17, 297-310.

Bellis, M., Hughes, K., Perkins, C., and Bennett, A. (2012) Protecting people, promoting health: A public health approach to violence prevention for England. London: NHS.

Boles, S. M., and Miotto, K. (2003) Substance abuse and violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 2, 155-174.

Brown, A. and Burton, D. L. (2010) Exploring the overlap in male juvenile sexual offending and general delinquency: Trauma, alcohol use and masculine beliefs. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19, 450-468.

Churchill, H. and Sen, R. (2016) Introduction: Intensive Family Support Services: Politics, Policy and Practice Across Contexts. Social Policy & Society 15(2), 251-261.

Crooks, C. V., Goodhall, G. R., Hughes, R., Jaffe, P. G., and Baker, L. L. (2007) Engaging Men and Boys in Preventing Violence against Women. Violence Against Women. 13(3), 217-239.

Dagirmanjian, F. B., Mahalik, J. R., Boland, J., Colbow, C., Dunn, J., Pomarico, A., Rappaport, D. (2016) How do men construct men’s violence? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(15), 2275-2297.

Derzon, J. (2010) The correspondence of family features with problem, aggressive, criminal, and violent behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 6(3), 263-292

Devaney, C & Dolan, P (2014) Voice and meaning: The wisdom of family support veterans. Child and family social work, 22, 10-20.

DOJNI (2012) Building safer, shared and confident communities: A community safety strategy for Northern Ireland 2012-2017. Belfast: Department of Justice NI.

Early Intervention Foundation (2015) What works to prevent gang involvement, youth violence and crime. London: Home Office.

Falshaw, L., Browne, K. D., and Hollin, C. R. (1996). Victim to offender: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1(4), 389–404.

Finkelhor, D. and Ormrod, R. (2000). Characteristics of crimes against Juveniles Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Flint, J., Batty, E., Parr, S., Nixon, J., Sanderson, D (2011) Evaluation of intensive intervention projects. London: Department of Education.

Gielen, A. C., Sleet, D. A., and DiClemente, R. J. (Eds.). (2006). Injury and violence prevention: Behavioral science theories, methods, and applications. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass.

Harland, K. (2011) Violent Youth Culture in Northern Ireland, Young Men, Violence and the Challenges of Peacebuilding. Youth & Society, 43, 2

Harland, K & McCready, S. (2015) Boys, young men and violence: Masculinities, education and practice. Palgrave Macmillan: UK.

Hasley, M. (2018) Child victims as adult offenders: Foregrounding the criminogenic effects of (unresolved) trauma and loss. British journal of criminology, 58, 17-36.

Home office (2016a) Ending gang violence and exploitation. London: Home Office.

Home office (2016b) Ending violence against women and girls strategy 2016 – 2020. London: Home Office.

Home Office (2018) Serious Violence Strategy. London: Home Office.

Jackson, V., Brown, K., and Stephen, J. (2016) The prevalence of childhood victimization experienced outside of the family: Findings from an English prevalence study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 51, 343-357.

Kerig, P. K. (2012) Introduction to Part I: Trauma and juvenile delinquency: Dynamics and developmental mechanisms. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 5(2), 83-87.

Krauss, H. H. (2006) Perspectives on Violence. The New York Academy of Sciences, 1087, 4-21.

Lynch, O., Joyce, C. (2018) Functions of collective victimhood: Political violence and the case of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. International Review of Victimology, 24(2), 183-197.

Malin, N., Tunmore, J., Wilock, A. (2014) How far does a whole family approach make a difference? Designing an evaluation framework to enable partners to assess and measure progress. Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 17(2), 63-92.

Maschi, T. and Bradley, C. (2008) Exploring the moderating influence of delinquent peers on the link between trauma, anger, and violence among male youth: Implications for social work practice. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 25(2), 125-138.

Matthews, S., Jewkes, R., and Abrahams N. (2011) “I Had a hard Life’: Exploring childhood adversity in the shaping of masculinities among men who killed an intimate partner in South Africa. British Journal of Criminology, 51(6), 960-977.

Mikhail, J. N and Nemeth, L. S. (2015) Trauma center based youth violence prevention programmes: An integrative review. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 17(5), 500-519.

Harland, K., and McCready, S. (2015) Boys, young men and violence: Masculinities, education and practice. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Muncie, J. (2009) Youth and Crime, 3rd ed, London: Sage.

ONS (2018) The nature of violent crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2017: A summary of violent crime from the year ending March 2017 Crime Survey for England and Wales and police recorded crime. London: Office for National Statistics.

Proctor, C. L., Linley, A. P., and Maltby, J. (2009) Youth Life Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 583-630.

Richter, L. M., Matthews, S., Kagura, J., and Nonterah, E. (2018) A longitudinal perspective on violence in the lives of South African children from the Birth to Twenty Plus cohort study in Johannesburg-Soweto. The South African Medical Journal, 108(3), 181-186.

Seaton, E (2007) Exposing the Invisible – Unravelling the Roots of Rural Boys’ Violence in Schools. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 3.

Sundaram, V (2013) Violence as understandable, deserved or unacceptable? Listening for gender in teenagers’ talk about violence. Gender and Education, 25(7), 889-906.

Tighe, A., Pistrang, N., Cadagli, L., Baruch, G. and Butler, S. (2012) Multisystemic therapy for young offenders: Families’ experience of therapeutic processes and outcomes, Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 2.

Tomlinson, M. F., Brown, M., and Hoaken, P. N. S. (2016) Recreational drug use and human aggressive behaviour: A comprehensive review since 2003. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 27, 9-29.

UNICEF (2017) A familiar face: Violence in the lives of children and adolescents. New York, NY: UNICEF.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401–408.

Violence Policy Center (2017) The relationship between community violence and trauma. Washington: VPC.

Biography: