Article: ‘On Road’ Youth Work: Inside England’s Gun Crime Capital

In this article, Craig Pinkney, Shona Robinson-Edwards and Martin Glynn explore their conception of 'On Road' youth work. The West Midlands has seen a rise in gun crime in recent years, which has given the region the title ‘England’s Gun Crime Capital’ for two consecutive years. Calls for new approaches to engage young people on the streets are raised as the possible response to gun crime and serious youth violence. This article explores the challenges faced ‘On Road’ by front-line youth work practitioners and identifies what they see as the key components of effective engagement, which reflect traditional youth work practices as well as contemporary experiences. The ‘On Road’ youth work approach builds on Glynn’s (2014) concept of ‘On Road Criminology’ and draws on the narratives of thirty front-line practitioners.

‘On Road Youth Work’ is our feature article for Youth Work Week 2018 as it offers one response to the Youth Work Week theme of ‘What is youth work?’ that challenges youth workers to rethink how they might engage with issues of gangs and youth violence.

In recent years, the West Midlands has been found to have persistently high levels of gun crime, often involving young people and those associated with gangs in particular. According to the Office of National Statistics (ONS) one in nine incidents of gun crime in England and Wales took place in the West Midlands in 2014, which means it had a higher gun crime rate for its population size than London’s Metropolitan Police Service area (ONS, 2015). The annual national statistics recorded 562 offences for the 12 months up to April 2015 – up from 540 in the previous year. This meant the West Midlands now had a gun crime rate of 20 per 100,000 people; higher than the 19 per 100,000 for the Metropolitan Police, 16 for Greater Manchester and 12 for Merseyside. In 2017, the data shows there were a total of 138 recorded firearms discharges in the West Midlands from January to September (ONS, 2017). This increased by 20% in 2018 (ONS, 2018). With this in mind, there is a debate amongst policy-makers, law enforcement, academics and youth work practitioners, as to what role does or should youth work play in the current climate of youth violence, not just in the West Midlands but across the United Kingdom (Anderson, 2017; Seal and Harris, 2016).

A new phenomenon or historic?

The level of firearm offences means families, communities and neighbourhoods are damaged by acts of both spontaneous and deliberate violence that kill or seriously injure (Anderson, 2017: 13). Research by Glynn (2014) and Anderson (2017) suggests that the reason for these issues within the West Midlands is directly linked to issues such as deprivation, high unemployment rates, poor education, lack of opportunity, closures of youth provision, and racism. We agree with these assertions but contribute further to the debate. We have suggested that, as social media has become more accessible, this has contributed to spates of violence within the region as gangs and young people use platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and Snapchat to highlight their criminal activity or broadcast ‘beefs’ they have with rival groups (Pinkney and Robinson-Edwards, 2018: 6). Moreover, we have argued that social media platforms, along with certain types of music, raise tensions within communities through the sense of having to ‘prove’ your narrative to online audiences (Pinkney and Robinson-Edwards, 2018: 6). Fraser (2017) agrees with this notion, proposing that there is a close association between mediated representations of gangs and marketization of authenticity, highlighting the relationship between socio-culture, gangs, rap and hip-hop. Densley (2013) presents an additional argument suggesting that ‘verbal agility’ is a valuable asset for gangs: by unloading an eloquent tirade of abuse upon their rivals, emcees raise the overall profile of the group and provide a dynamic source of entertainment for its members.

Despite the recent drivers or causes of gun crime within the West Midlands, it is important to highlight that this phenomenon of gun violence is not new to the West Midlands, or Birmingham specifically (Seal and Harris, 2016). As early as the eighteenth century, gun manufacturers in Birmingham faced a lot of criticism for their involvement in violence, as the city was the epicentre of gun making and distribution in Great Britain (Chin, 2013). Satia (2013, in Satyand Samuels, 2013) contends that the British state’s insatiable need for guns to meet wartime demand created a ‘military-industrial society’ and spurred the great economic transformations of the age, including the industrial revolution. Whilst the country was moving toward a ‘military-industrial society’, the criminal underworld was benefitting from gun trading through ready access to firearms. For example, in the 1890s, Birmingham was known as a dangerous city as the notorious street gang known as the ‘Peaky Blinders’ were infamous for their violence (Chin, 2013). Feuds between rival groups resulted in much bloodshed within the city (ibid.). In more recent times, gang feuds between two of Birmingham’s most notorious streets gangs ‘The Burger Bar Crew’ and ‘The Johnsons Crew’ resulted in the murders of Charlene Ellis and Letisha Shakespeare in 2003 (Sturcke, 2005). Gang feuds today tend to be over territory or ‘postcodes’ between splinters or sub-groups of young people that do not necessarily have direct affiliations to the two gangs mentioned previously.

Youth Work Practice

Even before austerity, Jeffs and Smith (2008) confirmed that youth work within communities was under threat by new structures of practice organised around outcomes, curriculum and delivery. Henry et al (2010) proclaim that contemporary society has demonstrated a ‘sizable shift toward accredited training; this relatively new slant to youth work practice has potentially greyed the lines between the formal and informal education approaches within youth work’ (2010: 26). As such, we argue there is now the need to better understand the components of an ‘On Road’ approach to youth work which rests firmly in the less structured and informal practices of youth work.

The context of youth work has developed over the years and continues to change, yet Henry et al (2010) assert that the young person and their immediate needs should remain the ‘defining feature’ of youth work environments. This study specifically focuses on the narratives and experiences of those youth workers on the front-line. These narratives advocate for an impactful approach to youth work that functions outside of the increasingly typical professional working hours of 9.00am to 6.00pm. This approach is particularly effective in engaging young people that live deviant lifestyles or live in dangerous environments (Seal and Harris, 2016).

‘On Road’ Youth Work

‘On Road’ youth work encompasses intersections of youth work and criminological theorising; locating the sight for critical enquiry within an environment which is urban, disorganised and in need of contemporary understanding. The practitioner and/or researcher is required to operate from an insider perspective, drawing heavily on ethnographic and phenomenological accounts of subjects through lived experiences. The ‘On Road’ approach to youth work builds upon the work of Glynn (2014) on ‘On Road Criminology’. Glynn (2014: 53) claims that ‘On Road Criminology’ is when one gains acceptance, approval, and permission from sections of the community who occupy the world of the ‘streets’. He further asserts that being an ‘On Road’ criminologist means having unprecedented access to spaces, which many practitioners and academics alike cannot and will not access.

According to Joseph and Gunter (2011) ‘On Road’ generally refers to a street culture that is played out in public places, such as street corners and housing estates, where individuals choose to spend the majority of their leisure time. However, Hallsworth and Silverstone (2009) elucidate that this notion of ‘On Road or Life on Road’ is not solely about where people spend their leisure time, rather it is a place where violence and its threat is everywhere. Arguably, ‘On Road’ youth work encompasses some of the points raised by Glynn (2014), Joseph and Gunter (2011) and Hallsworth and Silverstone (2009). Although practice in this context often seems intriguing, many practitioners hold concerns regarding working with young people ‘On Road’. Glynn (2014) highlights that workers will often avoid entering a world where an understanding of the ‘code of the streets’ is essential for practice.

The ‘code of the streets’ is a term referred to by Anderson (1999) as a street-level ‘survival of the fittest’ philosophy. Glynn (2014) further adds to this statement, asserting that this notion revolves around the ability to navigate the perils of violence, gang culture, drugs and extreme social deprivation. Subsequently, individuals who understand and manage the ‘code of the streets’ often use extreme measures to control sections of the communities in which they reside (Glynn, 2014: 92). However, this may often raise safeguarding concerns, which as a result can also prevent front-line practitioners engaging with young people ‘On Road’.

Though the term ‘On Road’ youth work is somewhat new, the fundamental principles build upon the work of Glynn (2014), Whyte (1943) and Goetschuis and Tash (1967). Whyte’s (1943) ethnographic study ‘Street Corner Society’ has been ‘highly praised’ in American Social Science (Andersson, 2014 :74). Van Maanen (2011 [1988]) compares ‘Street Corner Society’ with Malinowski’s ‘Argonauts of the Western Pacific’ (1985 [1922]), further suggesting that generations of students have ‘emulated Whyte’s work by adopting his intimate, live-in reportorial fieldwork style in a variety of community settings’ (Andersson, 2014: 79). Whyte (1943) explored social interactions, networking and everyday life among Italian-American Men in Boston’s North End (Andersson, 2014). Whyte (1943) observed and explored local street gangs, the ‘corner boys’, social organisation and mobility – some of the fundamental issues relating to the term ‘On Road’. Whyte spent ‘three and a half years between 1936 and 1940 in the North End, which also gave him a unique opportunity to observe at close range’ (Andersson, 2014: 79). Therefore, some elements highlighted by Glynn (2014) relating to gangs, gang culture and deprivation have already been explored in some depth by Whyte (1943).

Although their work is separated by decades, similar sentiments are echoed in the work of Goetschuis and Tash (1967). Muriel Tash and George Goetschuis commissioned a twelve-month experiment which was carried out by five youth workers, in order to identify whether contact could be made with young people through a mobile coffee stall on a street corner (Batsleer and Davies, 2010). In the United Kingdom, the work of Goetschuis and Tash (1967) has been one of the most sustained pieces of research into youth work due to its success in making contact with young people within their community. Arguably, this insinuates that ‘On Road’ research has, in fact, been practised among communities long prior to the work of Glynn (2014). The work of Goetschuis and Tash (1967) may even question the originality of Glynn’s (2014) concept. Over youth work’s history, youth workers have been accepted by the younger population, gaining the privilege of unprecedented access to spaces such as street corners, dance halls and public housing, in order to work with them in the heart of the community. Glynn (2014) takes further such community-based practice to develop the concept of ‘On Road Criminology’ with a new contemporary relevance. What previous ‘On Road’ studies potentially lack that is made explicit by Glynn (2014) is a recognition of the intersections of social attributes such as race, age, culture and social class as well as a specific criminological focus.

Methodology

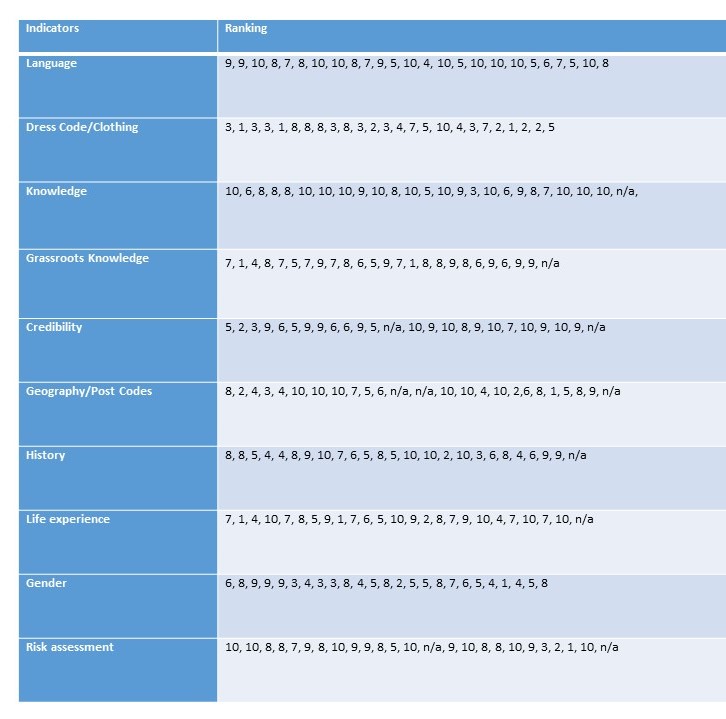

The research presented in this article utilised a mixed-method approach which consisted of questionnaires and a semi-structured focus group discussion that involved thirty professionals from across Birmingham. The focus group was conducted as part of an emergency meeting organised and facilitated by Craig Pinkney (one of this article’s authors and the researcher who conducted the study) following a fatality in the city. Most of the research participants had experience as front-line practitioners and came from a number of professional backgrounds including but not limited to Youth Workers, Outreach Workers, Mediators, Youth Offending/Probation Officers, Support Workers, and Behavioural Managers. The aim of the meeting was to bring together a range of youth practitioners to discuss how to effectively address the recent spate of violence within the city and to develop a practical framework that can be used by those working in gang impacted environments. Participants were from mixed backgrounds, in terms of gender, race and religion. The focus group used semi-structured questions, which then evolved into a well-rounded discussion. A separate questionnaire which sought to explore the importance of and qualities needed for ‘On Road’ youth work was given to participants to complete separately. Narrative analysis was applied to the data from the focus groups. The principles of Grounded Theory were used as a means of developing theory from the qualitative data (Glaser and Strauss, 1976; Charmaz, 2006). We then used the main themes emerging from the narratives from the focus groups to explore ‘the lived experience’ of those on the front-line. From this, we identified the key characteristics or indicators a worker needs to possess to be effective when working ‘On Road’. These characteristics informed the categories used in the questionnaire. Through the questionnaire, participants were asked to rank 10 components as to their importance to effective ‘On Road’ youth work, with 1 being the least important and 10 the most. The following measures were used to interpret the data clearly: 7-10 Considered Important; 4-6 Worthy of Consideration; 1-3 Not Considered Important.

Practitioner Responses

Table 1: practitioner responses to the questionnaire

The findings from the focus group and subsequent questionnaire provide a picture of the competencies needed to work in environments where young people are vulnerable to involvement with gangs and/or violence. Overall, from the research, the following themes emerged as most significant: Language; Knowledge and Positionality.

Theme One – Language

Participants specified language as being an important component of effective front-line engagement. In every geographical location where young people occupy space, there will be certain types of words, dialects, slang and various forms of body language, used to communicate. This ‘insider’ communication is also used to confirm who young people identify with and to distinguish those who ‘belong’ with them from those they consider outsiders, enemies, or those in authority. It is important to understand the impact which the evolution of technology, popular culture and globalisation have had on language and communication. Words that hold no significant meaning today may have significant meaning and connotations in the near future. Also, words that have been used historically to slander, ridicule or degrade people, in some cases are re-appropriated and used in terms of endearment and as markers of belonging. A contentious example that emerged in discussions with practitioners is the word ‘N****r’. Although some practitioners are firmly against the use of this term, others argue the importance of being open to exploring and understanding its use with young people ‘On Road’. It is not necessarily about practitioners adopting all the language of the street – careful consideration is needed especially where terms represent ethnic or cultural markers of belonging. However, it is about engaging authentically and relevantly. This relates to the theme of Positionality, and particularly the notion of credibility, discussed below.

Theme Two – Knowledge

Knowledge was considered to be an essential tool for front-line practitioners. If sound knowledge is not obtained it can hinder access, engagement and potentially put the young person and practitioner at risk. Before engaging in ‘On Road’ youth work, fundamental questions should be asked about the area such as: who the dominant people are that reside there; whether any links exist with families, elders, local shop owners or faith leaders in the community; the perceptions of local people about the practitioners and their work. The consequences of not having knowledge are numerous. Practitioners may struggle to gain access, especially on a personal level. Having knowledge in gang impacted environments enables the practitioners to navigate through complex and sometimes hostile environments, and ultimately is what keeps them safe.

Theme Three – Positionality

The positionality of front-line practitioners (how they position themselves or are positioned by the community) was highlighted as being both significant and influential. Factors such as gender, clothing and credibility were particularly emphasised by the practitioners as having an impact on their positionality. Gender was believed to heavily influence the role and perception of the practitioner, with some women viewed as carers and nurturers, whilst men more often viewed as protectors and providers. Adding to this challenge of how the practitioner is positioned was the role of clothing. Some participants expressed clothing to be an important attribute in regards to effectively engaging with young people who were positioned by some practitioners as ‘hard to reach, deviant or violent’. Having said this, several participants did not view clothing as a particularly important characteristic. Arguably, occupation is an influential factor here. Almost half of the participants who did not view clothing as significantly important worked in settings which are generally office-based and do not require the practitioner to dress informally because they are bringing young people into their environment rather than the other way round. However, those that worked in environments engaging with young people on the front-line, generally agreed that clothing is an important and fundamental issue relating to the positionality of the youth worker and how they were accepted and perceived.

Clothing can be viewed as a symbolic language. As such, the subconscious messages certain types of clothing portray must be acknowledged. For example, a police officer in uniform attempting to engage positively with young people on the street may face challenges. The uniform may be viewed as authoritative, representing the unequal power dynamics that exist between young people and police, and therefore creating a boundary between the police officer and the group. Young people may also not want to be seen working or cooperating with the police on the street – this may even cause significant problems for them in their community. A uniform might also, for many, represent notions of injustice, discrimination and negative experiences (Johnson, 2013). Conversely, aspects of clothing may be materialistic symbols among certain groups and command respect or represent unity and acceptance. Participants did not suggest that front-line practitioners should wear all the clothing that young people find affinity with. However, it was suggested that when engaging with youth ‘On Road’ it is appropriate to wear garments that reflect aspects of the culture they identify with.

The overall credibility of the youth worker was deemed an important aspect of positionality. Credibility was described as the ‘VIP pass’ to access within the community. A practitioner might tick all of the boxes in terms of external outlook and yet lack credibility. When they enter a particular space and before they even speak, the young people will have already asked the question ‘who is that man/woman?’ If their answer to this question does not make the questioner/s feel safe, secure or comfortable, then the individual or group will not be willing to engage. Practitioners felt that they can gain credibility through visibility in the community or in areas that they intend to serve. Getting involved in a range of community events, volunteering for credible youth organisations, and becoming more familiar with the community before attempting to engage ‘On Road’ were given as examples of how they do this.

Conclusion

The themes of this research are important to the future development and understanding of street-based youth work. The research has particular relevance in inner cities where the challenges linked to violence, extremism and gangs are arguably most challenging. It is important to understand the context of ‘On Road’ youth work, and the lived experiences highlighted by those on the front-line. This article has explored the themes that emerged from the narratives of thirty front-line practitioners. Whilst we recognise the limits of generalising the findings too extensively, we argue that they contribute to the wider academic research surrounding youth work practice in the UK. In particular, they contribute to a wider understanding of the difficulties, expectations, challenges and roles of those working on the front-line, in inner-city communities, engaging young people in violent or gang-impacted environments.

In conclusion, we suggest that understanding young people, youth work and the experiences of practitioners is an ongoing journey that this research contributes new reflections to. The narratives of the practitioners in this study emphasised the importance of the Language, Knowledge and Positionality of front-line youth workers, when working ‘On Road’. Moreover, ongoing developments in technology, the use of social media, government policy discourses and responses to issues such as gangs and gang-related violence, require new and innovative ways of engaging young people. For those youth workers that have the passion to work with young people on the front-line, our conception of ‘On Road’ youth work might be used as a model to engage with young people around the issues of gangs and violence in such spaces.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 10 February 2020

References:

Anderson, C. (2017) Commission on Gangs and Violence: Uniting to improve safety. West Midlands Police and Crime Commission.

Anderson, E. (1999) Code of the Street. New York: W. W. Norton.

Andersson, O. (2014). ‘William Foote Whyte, Street Corner Society and social organization’ Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences, Vol. 50 (1), 79-103.

Batsleer, J. R. and Davies, B. (2010) What is Youth Work? Great Britain: Learning Matters.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Chin, C. (2013) ‘Birmingham’s Peaky Blinders – in fact… and fiction: With the new TV series about Brum’s historic gangs causing national attention, we go back to the city’s newspaper reports to unravel the truth.’ Birmingham Mail. https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/whats-on/tv/birminghams-peaky-blinders—fact-5912820 Accessed 27th Jan, 2018.

Densley, J. (2013). How gangs work. An Ethnography of Youth Violence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fraser, A. (2017). Gangs & Crime: Critical Alternatives. London: Sage.

Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967). Grounded theory: The discovery of grounded theory. Sociology, 12, 27-49.

Glynn, M. (2014) Black Men, Invisibility, and Desistance from Crime: Towards a Critical Race Theory from Crime. London: Routledge.

Goetschius, G.W. and Tash, M.J. (1967). Working with Unattached Youth. The problem, Approach, Method. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hallsworth, S. and Silverstone, D. (2009) ‘That’s life innit’ A British Perspective on Guns, Crime and Social Order. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 9(3), 359-377.

Henry, P., Morgan, S., and Hammond, M. (2010). ‘Building Relationships through Effective Interpersonal Engagement: A Training Model for Youth Workers’. Youth Studies Ireland. Vol. 5 (2), 25-38.

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M.K. (2008) ‘Valuing Youth Work’, Youth and Policy, 100, 277–302.

Johnson, U. (2013) Psycho-Academic Holocaust: The Special Education & ADHD Wars Against Black Boys. USA: Prince of Pan-Africanism Publishing.

Joseph, I. and Gunter, A. (2011). ‘What’s a gang and what’s race got to do with it?’ In Joseph, I., Gunter, A., Hallsworth, S., Young, T. and Adekunie, F. Gangs revisited: what’s a gang and what’s race got to do with it. London: Runnymede Trust.

Malinowski, B. (1985 [1922]). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

ONS (2015). Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2015. Released: 26 April 2016. London: Office for National Statistics.

ONS (2017). Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2017. Released: 25 January 2018. London: Office for National Statistics

ONS (2018). Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2018. Release Date: 18 October 2018. London: Office for National Statistics.

Pinkney, C. and Robinson-Edwards, S. (2018) Gangs, music and the mediatisation of crime: expressions, violations and validations. Safer Communities, 17(2), 103-118.

Satyanand Samuels, P. (2013) Gun making and the origins of the Industrial Revolution: How wartime demand led the British government to the create a factory-style system of gun manufacture. http://gender.stanford.edu/news/2013/gun-making-and-origins-industrial-revolution Accessed 27th Jan, 2018.

Seal, M. and Harris, P. (2016). Responding to youth violence through youth work. Bristol: Policy Press.

Sturcke, J. (2005) ‘Four found guilty of new year murders’. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/mar/18/ukguns.ukcrime Accessed 25th May 2018.

Van Maanen, J. (2011 [1988]). Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Whyte, W. F. (1943). Street Corner Society: The Social Structure of an Italian Slum. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Biography:

Craig Pinkney is a Criminologist, Urban Youth Specialist, Lecturer at University College Birmingham, PhD Researcher, and one of the UK’s leading thinkers/doers in responding to Gangs and Serious Youth Violence. He has over 15 years of experience as an outreach worker, transformational speaker, gang exit strategist, mediator, mentor, filmmaker and advisor. Craig is well known for working with some of Birmingham’s most challenging young people, potentially high-risk offenders, victims of gang violence and young people who are deemed as hard to reach. Craig has authored and co-authored a number of peer-reviewed academic publications and his research interests include urban street gangs, youth violence, social media and violence, trauma and desistance. His PhD study looks at the link between social media, gangs and youth violence in the West Midlands. Website: www.craigpinkney.com

Shona Robinson-Edwards is a PhD Researcher and Assistant Lecturer in Criminology at Birmingham City University. Her areas of interest include Offending, Rehabilitation, Religion and Desistance; reflected in her current PhD study which looks at the role of Religion in the Lives of Offenders Convicted of Homicide Offences. Shona’s research sits in the Positive Criminology research cluster at the university and her thesis seeks to provide a platform for those whose voices are rarely heard. It is further hoped that this research will explore what might prevent or help people to move away from crime. Website: http://www.bcu.ac.uk/social-sciences/criminology/staff/shona-robinson-edwards

Dr Martin Glynn is an experienced and internationally renowned educator, theatre director, and dramatist who has written for theatre, radio, and television. He has also published many poetry books, alongside building a growing reputation as an author of children’s books. As a renowned criminologist, Martin has over 3 decades of experience of working in criminal justice, public health, and educational settings. He has a Cert. Ed, a Master’s degree in criminal justice policy and practice, and a PhD from Birmingham City University. He is also a Winston Churchill Fellow (2010) and was awarded the prestigious ‘Pol-Roger’ award from the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust (2012) for outstanding service to the field of criminology. Martin is also a full member of both the Writers Guild of Great Britain and EQUITY, the actors union. Dr Glynn is the founder and creator director of PLATFORM-DATA VERBALIZATION LAB.