Home > Articles > Social group work with young people in Tamil Nadu, India: A case study of civic engagement

Article: Social group work with young people in Tamil Nadu, India: A case study of civic engagement

Author: Gadha M. Das & Dr. Subramanian Lalitha | Tags: Risky behavior, Scheduled Caste, Social group work, social work, youth

Das and Lalitha write about a 'Social Group Work' intervention with disaffected young people from Katchipattu village, Kancheepuram District, Tamil Nadu, India. This case study shows the power of organising the youth as agents of social change and educating them about the causes of their risky behaviours.

Introduction

The younger generations are typically regarded as the agents of the future because they embody the dynamics of change and the expectations that are contained in the horizon. By assimilating the experiences of a previous generation, youth can create societal change and gradual improvement from the range of experiences that are already available (Henze, 2015). In society, youth are viewed as ‘in transition’ or ‘not fully formed’ individuals, resulting in a propensity to exclude youth in decision-making. But the distinctive contribution that the youth can offer to society must be utilized so that youth must be decision-makers rather than simply the subject of adult decisions (Offerdahl, Evangelides and Powers, 2014).

This paper is based on fieldwork with young people undertaken as part of a PhD in Katchipattu village, a predominantly scheduled caste community in Sriperumbudur Town Panchayat, Tamil Nadu, India. The reputation of young people in Katchipattu Village as anti-social has persisted for many generations. Due to their reputation, they find it challenging to interact socially with adjacent populations and gain work in the community. Their ability to acquire resources is further hampered by involvement in illicit activities and risky behaviours, making it more difficult for them to attain a sustainable way of life. Youth who had feelings of helplessness and confusion about their identities were more likely to act out and lacked the will to better themselves or their community. The objectives of the study were:

- To help youth understand the reasons why they engage in risky behaviour.

- To organize youth in the village of Katchipattu as agents of social change.

Approach

Lalitha (2020) determined that group-based interventions with these young people would be successful in overcoming their issues because of their strong peer bonds. During her post-doctoral research (2017-2019) she started a youth group in the community and urged its members to get involved in pond restoration. Youth organising for continued civic engagement was viewed as essential for youth to achieve a positive identity, community recognition, and personal development (Lalitha, 2020). Based on the results of Lalitha’s study, our intervention was designed to continue social group work support for the youth in Katchippattu village.

Social group work is a technique that uses intentional group interactions to enhance social functioning and help people better handle their individual, social, and civic difficulties. As a result of group work, youth are able to identify their own issues, set their own goals, and take independent action. It assists them in analysing their current situations, recognising their own problems, learning a new coping technique, and putting their own solutions into practice (Antony, 2020; Arches, 2012).

Problematised youth

Youth may be viewed simultaneously as a human resource and a problem/risk group (Anaut-Bravo & Raya-Díez, 2020). As a result of changes in social institutions such as the family and factors such as industrialization, urbanization, and environmental factors, the youth are increasingly confronted with persistent and recurrent social problems, including those related to health, unemployment, and drug abuse. Since youth social exclusion is on the rise, social work focusing on youth development requires high levels of expertise (Merfeldaite & Dilyte, 2016). Social workers must address these new societal concerns while focusing their efforts on factors that degrade youth personalities, providing basic needs, enhancing relationships, coping with stress, and developing a positive attitude about oneself and others (Jeremiah Otieno et al., 2018).[1]

Social group work with young people

Social work with groups is a constantly expanding practice area. It is a unique, exciting, and dynamic approach to assisting people in making the right changes in their life. In contrast to the related social work methods of casework and community organization, social group work focuses primarily on providing group experiences to meet normal developmental needs, aid in preventing social breakdown, facilitate corrective and rehabilitative goals, and encourage citizen participation and responsible social action (Shakil, 2015).

Merfeldait and Dilyt (2016) defined the competencies of social workers who work with youth as professional and personal competencies. Youth-serving social workers placed a high priority on establishing professional relationships based on trust. The capacity to work efficiently in a group is one of the most crucial aspects of professional competence. Personal competencies of youth-serving social workers include empathy, the capacity to understand youth, initiative, and the ability to respond flexibly and creatively to various situations.

Theoretical framework: Ecological system theory and youth development

The ecological system theory of human development served as the theoretical foundation for this social groupwork intervention. According to this theory, the environment in which young people develop is viewed as a group of nested structures, including the microsystem, the exosystem, and the macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1992). People’s interactions with their immediate environment, such as those with their parents and peers, are included in the microsystem. Neighborhood characteristics, which are further-reaching circumstances that could indirectly affect development, are examples of exosystem traits. The more comprehensive socio-cultural backdrop is made up of the macrosystem, which includes laws, customs, political beliefs, and the media. It is significant that this theory acknowledges how certain characteristics interact with environmental factors to affect development (Ajrouch et al., 2016). This theory supports a collaborative approach to youth development. Youths pass through their mesosystem—which consists of their homes, campuses, places of employment, youth activities, and other leisure time and peer situations—every day. The relationships between these environments have an impact on how young people develop. Collaborations for youth development at the community level are fine examples of mesosystems that are specifically created to promote positive growth. This strategy works because community values related to youth development are created through collaborations so frequently and are widely embraced (Duerden & Witt, 2010).

Selection of members

The intervention happened from July until December 2019. According to India’s National Youth Policy, youth are classified as being between the ages of 15 and 29. The youths who volunteered for this social group work were members of the Dr. Ambedkar Youth Welfare Association Youth Club’s executive committee and were in the age range of 19 to 28. The group included a college student, a casual labourer, a contract worker for a company, an entrepreneur, and someone who relied on unlawful means of support, reflecting the diversity of the village’s youth population. The objective of the group work was to integrate the youth with the community and to develop self-awareness. Youths’ needs were taken into account when scheduling the Social Group Work sessions. All of these youths have studied high school or above and come from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. In spite of the fact that all of these youths possess multiple skills, alcohol addiction, unemployment, and lack of opportunities drove them into crime.

Negotiating time and venue

According to Brendtro et al. (2002), understanding a young person’s social background is a prerequisite for comprehending their behaviour. So, the Public Distribution System Shop (PDS) in Katchipattu was chosen as the location for meetings with young people because it is where they hang out.Most meetings were between 4 and 6 p.m. because that is when they found it most convenient. It was possible to do social group work efficiently since the youth’s choice of time and location was given due thought. Thus, it was strongly realised that the social workers who are trained in a range of approaches depend mostly on the level of rapport they build with clients (Brendtro et al., 2002; Smyth & Eaton-Erickson, 2009). The authors visited youths’ homes, met with their parents and other family members, shared food and accepted cultural differences, and attended invited family gatherings, which helped them win the trust of the youths.

Social Group Work Sessions

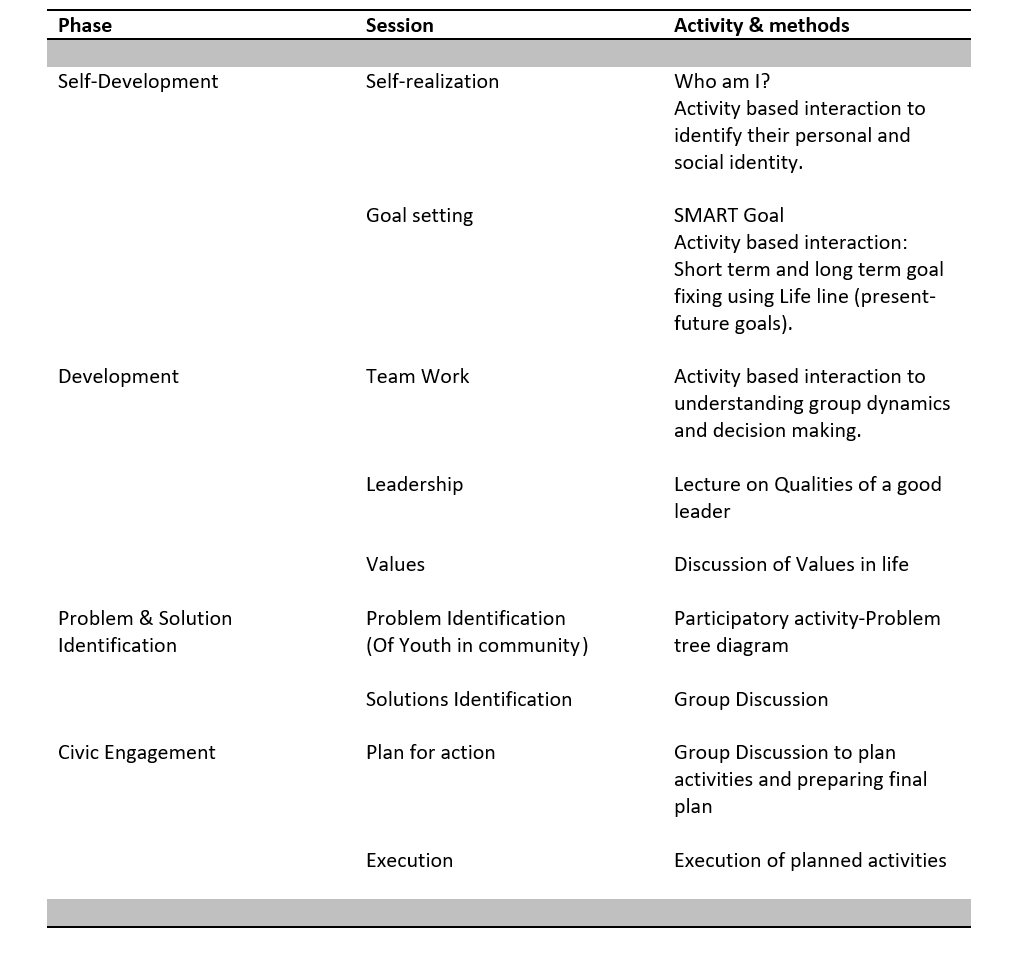

In order to obtain opinions and make the required adjustments, young people were given a schedule for completing social group work during the group formation session. The intervention involved nine sessions in four phases: personal development, group development, problem and solution identification, and civic engagement/action (see Table 1) (Antony, 2020; Arches, 2012; Lindsay & Orton, 2014).

Table 1 Schedule of social group work intervention with youth in Katchipattu

To encourage the youth to open up and feel comfortable, each session started with a brief informal comment on films, Tamil cultures, contemporaneous environmental challenges, and current political happenings in India. Introspection into one’s own identity in relation to their family and community was the focus of the first session. Mr. M stated that “Everyone says we are worthless, unemployed, youth drinking alcohol while sitting idle in this PDS shop,” The other members all agreed with this statement. This suggests that the villagers view young people as problematic. Mr. T said, “we are unsure of our skills and abilities, and we haven’t noticed any aptitude or competence within ourselves. We are never satisfied with our skill set.” Later, the youths started talking about defining objectives for the youth club to operate in a way that would change their negative reputation in their local community during the second goal-making session, which was held after the presentation on SMART goals using flip charts. The discussions focused on using the youth club as a civic engagement organisation so that the villagers’ (adults’) viewpoints will change and they will embrace youth competence and trustworthiness.

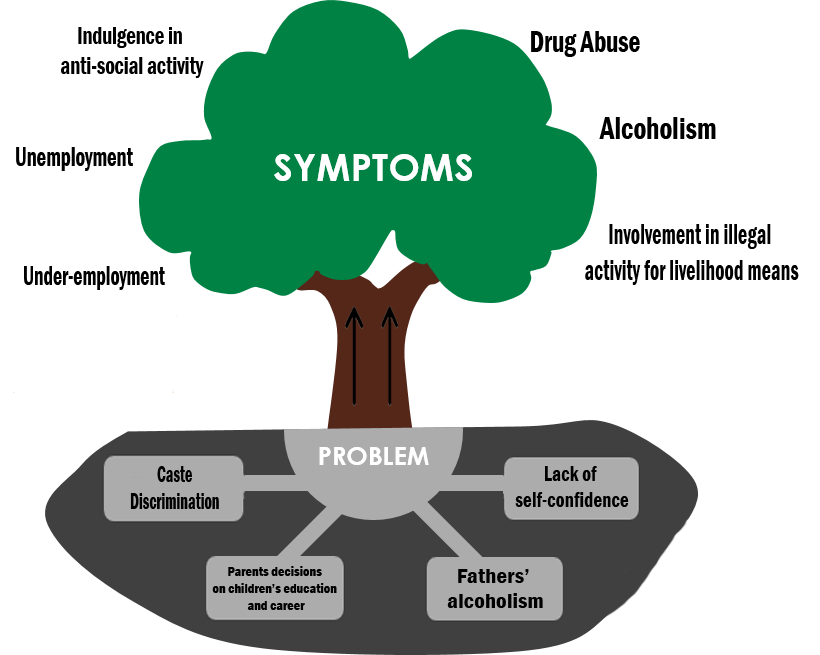

They learned about group dynamics, leadership skills, and life values during phase two. The creation of a participatory problem tree diagram and group discussions made up the third phase of the problem and solution identification process. Figure 1 (below) shows the problem tree diagram for the youth in the Katchipattu, which illustrates that group members identified caste discrimination, parental control over children’s education and employment, fathers’ drunkenness, and low self-esteem as contributing factors to youth problems. According to Mr. T, who said, “When I’m not drunk, I feel sorry for myself because I can’t do anything, but when we drink, we forget everything.” They made the decision to immediately change their reputation in the community from “worthless youth” to “trustworthy and positive youths.” They desire the youth club to serve as a platform for their civic participation. The fourth phase took four months to complete before we continued. In order to operate the youth club as a formal organisation for the welfare of youth and the community, the youths decided to establish it under the Tamil Nadu Societies Registration Act of 1975.

Figure 1 Problem tree diagram

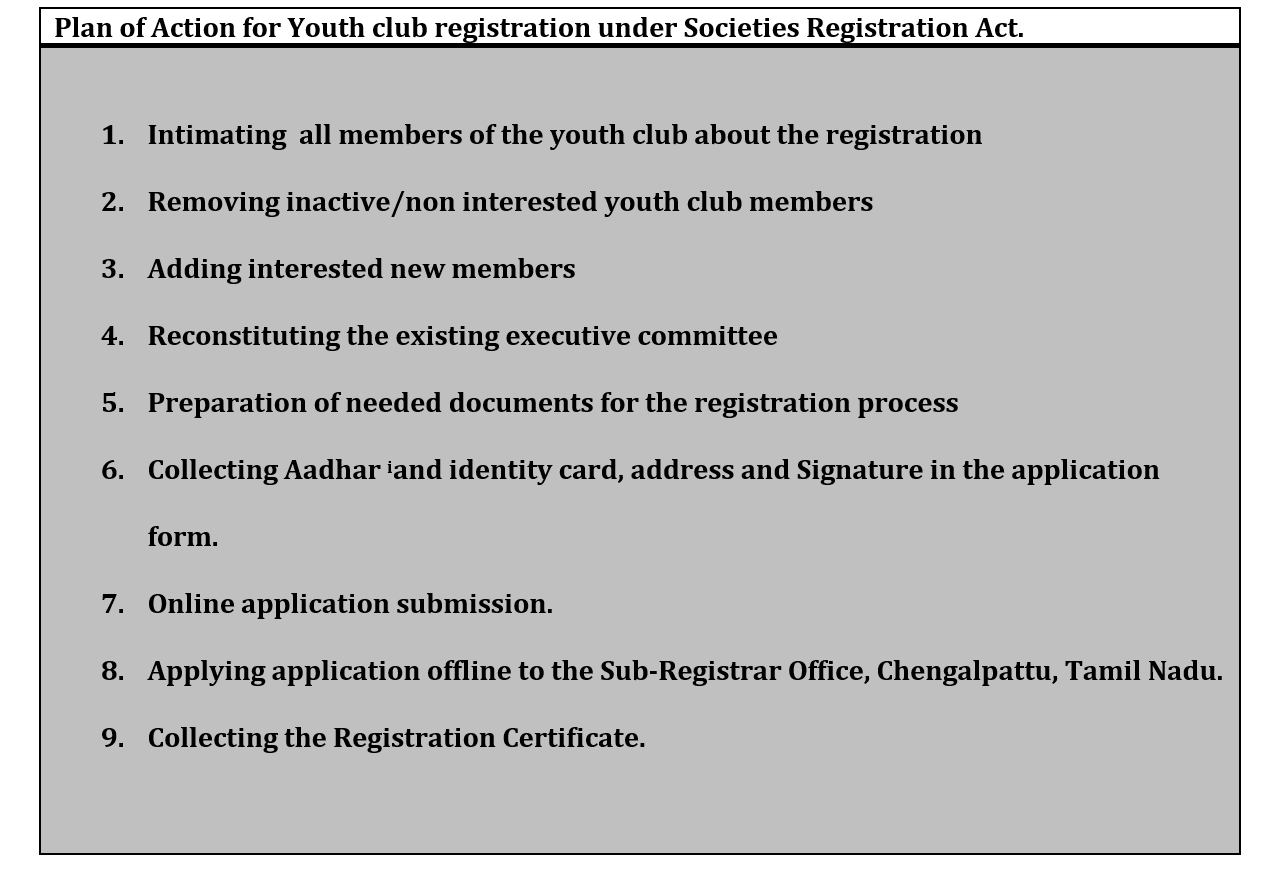

Two meetings were required to develop the action plan (see Table 2). In these sessions, the facilitator acted as a consultant and imparted knowledge on the registration procedure.

[1] Aadhar card is a 12 digit verifiable identification number issued to the resident of India at free of cost by the Unique Identification Authority of India.

Table 2 Plan prepared by the youth for civic engagement

After the Social Group Work intervention, the youths resolved to meet with every member of the youth club to persuade them to register the youth club under the Societies Registration Act. They also assigned tasks to themselves at the subsequent meeting. After that, a new executive committee was formed. Together, the members of the youth club prepared the paperwork required for registration, which took place over the course of two months. Finally, on September 30, 2019, the application was delivered to the Registrar Office in the Tamil Nadu district of Chengalpattu, and on December 18, 2019, the Executive Members of the Youth Club collected the registration certificate for the club.

Outcome of intervention

For the social group work intervention with youths, the reciprocal model of Social Group Work proposed by Schwart (1961) as cited by Pappel & Rothman (1966) was used. The intervention provided space for the youths to reflect upon on their identities in their families and communities. It was realized that their issues were a result of their adverse childhood experiences. Even if they couldn’t handle some issues on their own, youth had a thought of giving up using alcohol and other substances. They made the decision to transform the label “worthless youth” into “worthy youth”, through civic involvement. They intended to create a good identity in the community by using the youth club as a platform for young engagement towards bettering their community. They intended to open an office for youth club as they wanted to use it to develop strong social capital. They also wanted to raise funds for that. To solve the issue of not being able to receive credit for their urgent needs, they also wanted to create a micro-credit system among the youth club members. These behavioural changes provide evidence that the social group work intervention was successful.

Conclusion

The purpose of this social group work intervention was to organise the youth as agents of social change by educating them about the causes of their risky behaviours. Youth in Katchipattu village face a number of problems, including caste-based social exclusion, low socioeconomic status, the gap between aspiration and achievement and unemployment, which were revealed through the social group work intervention. The intervention was established in order to address these problems in a way that would involve the youth community in looking for solutions. In this village, social group work was considered essential since young people needed to be active in problem-solving and skill development. Youth were able to come together in the evenings to discuss their difficulties and share their life experiences as a result of the social group work experience. Youth took part in the analysis process to identify their problems and understand their role in the development of the community. It requires continuous social engagement through social group work and other social work interventions for these young people to solve problems and integrate into society. Engaging with young people from similar cultural backgrounds will be guided by this social group intervention. In the initial phase of the intervention, self-reflection, existing family interaction patterns, and values acquired by youth were explored. Since they lack social capital, they require more exposure to positive experiences, social connections, and community engagement for social purposes in order to live better. Youth development can be envisioned through additional interventions designed to develop their personalities and develop their talents, along with a formal organization structure. Youth civic involvement will lead to a social shift in the community. For the next generation, this will provide new perspectives on life opportunities and inspiring role models.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 23 June 2023

Footnotes:

Ethical considerations

The doctoral committee of the PhD program approved the field work intervention. Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) approval was obtained by the authors.

Funding

No funds were received for this Social Group Intervention

[1] While youth work is distinct from social work in some countries such as the UK, in India youth work is part of social work.

[2] PDS shops enable people to buy essential goods at fair prices, subsidized by the government.

References:

Ajrouch, K. J., Hakim-Larson, J., & Fakih, R. R. (2016). Youth Development: An ecological Approach to Identity. 13.

Anaut-Bravo, S., & Raya-Díez, E. (2020). The social reality of youth and social work: Between visibility and invisibility. Social Work Education, 39(6), 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1682541

Anderson, C. W. (2013). Youth, the ‘Arab Spring,’ and Social Movements. Review of Middle East Studies, 47(2), 150–156. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43741449

Antony, S. (2020). Social Group Work: Guidance for Practice. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13113.72800

Arches, J. (2012). The role of groupwork in social action projects with youth. Groupwork, 22(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1921/095182412X655273

Brendtro, L. K., Brokenleg, M., & Van Bockern, S. (2002). Reclaiming Youth at Risk: Our Hope for the Future. Revised Edition. National Educational Service, 304 West Kirkwood Avenue, Suite 2, Bloomington, IN 47404-5132 (Item No.

Duerden, M., & Witt, P. (2010). An ecological systems theory perspective on youth programming. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 28, 108–120.

Henze, V. (2015). On the Concept of Youth – Some Reflections on Theory. 15.

Jeremiah Otieno, E., Osiru Okatta, T., Muhingi Ndege, W., Mutavi, T., Tedd Okuku, M., Okoth Odero, Dr. V., & Mwendwa, D. K. (2018). The Emerging Social Work techniques in Youth Empowerment programs: A case Study of Youth Empowerment Organizations in Nairobi County. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 6(02). https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v6i2.el01

Lalitha, S. (2020). Transfer of Technology for Youth Civic Engagement in Pond Restoration: An Intervention Study Using the Social Group Work Method. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(1), 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa221

Lindsay, T., & Orton, S. (2014). Group Work Practice in Social Work (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Merfeldaitė, O., & Dilytė, J. (2016). Competencies of Social Workers for Work with Youth: Case Analysis. Socieity. Integration. Education. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, 4, 97. https://doi.org/10.17770/sie2016vol4.1548

Offerdahl, K., Evangelides, A. and Powers, M. (2014). Overcoming Youth Marginalization. Columbia Global Policy Initiative. Retrieved 27 June 2022, from https://www.un.org/youthenvoy/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Columbia-Youth-Report-FINAL_26-July-2014.pdf.

Shakil, D. M. (2015). Social Work with Group: An Empowering Approach for Solving Human Problems. https://www.academia.edu/24410411/Social_Work_with_Group_An_Empowering_Approach_for_Solving_Human_Problems

Smyth, P., & Eaton-Erickson, A. (2009). Making the Connection: Strategies for Working with High-risk Youth.

Biography:

Gadha M Das, Phd Scholar, Department of Social Work, Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development.

Dr. S Lalitha, Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development.