Article: South Africa’s universities’ lack of policy addressing gender-based violence on its student population

South Africa has an urban youthful population. Its National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 as a policy aims at improving the education system by increasing student retention rates to 90 percent, increase enrolment at universities to 70 percent by 2030 and increase the number of students eligible to study towards maths and science based degrees to 450,000 by 2030. However, it has become evident that South Africa’s universities do not have the policy to address gender-based violence, which has plagued its campuses and country at large. There is a risk that NDP 2030 policy could fail when there is no policy addressing gender-based violence (GBV) at South Africa’s universities. This paper provides an overview of GBV in South Africa and the lack of policy addressing GBV among university students. I situate the individual young women’s experience as a central point in this scourge of GBV in South Africa.

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a worldwide epidemic. Globally, it is estimated that one in three women will be beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime by an intimate partner or non-partners (Schwitters et al., 2015). Sexual violence in UK universities has been the focus of significant media attention with 1 in 4 women students reporting unwanted sexual behaviour during their studies and 1 in 5 experiencing sexual harassment during their first week term (McCarry & Donaldson, 2017). The social factors that influence GBV’s existence are patriarchy (Walby, 1989), hegemonic constructions of femininity (Jewkes & Morrel, 2010) and people’s position in structures of inequality and at the intersections of race, class and gender, women may be subjected to compound oppression (Campbell 1991).

The focus on GBV stems from the knowledge that it is one of the most gendered human rights violations in South Africa. The impact of GBV and violence against women on the country’s economic prospects is enormous and appears to play a role in hampering national efforts to reduce poverty, which is prevalent among women. For example, GBV costs South Africa between R28.4 billion per year or between 0.9 percent and 1.3 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), annually (KPMG 2014).

GBV can be conceptualised as a multidimensional phenomenon. The South African Domestic Violence Act 116 of 1998 defines GBV as: physical abuse; sexual abuse; emotional, verbal and psychological abuse; economic abuse; intimidation; harassment; stalking; damage to property; entry into the complainant’s residence without consent if the parties do not share the same residence; or any other controlling or abusive behaviour towards a complainant, where such conduct harms or may cause imminent harm to the safety, health or wellbeing of the complainant (South Africa 1998). South Africa as a country has ratified several international and regional conventions that were domesticated into the national policies. The General Recommendations of Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Violence against Women (CEDAW), views GBV as a form of discrimination that constitutes a serious obstacle in the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms by women (Commission for Gender Equality 2016a).

South Africa has the tendency to fail to meet its obligations for timeous reporting, combining and compressing reports in translating policy commitments into practical outcomes, especially in areas of policy execution and management of global and regional commitments on gender issues (Commission for Gender Equality, 2016b). This tendency has contributed to the lack of recognition of violence towards women students at South Africa’s universities. GBV does not only interfere with students’ academic performances and careers but also, interferes with the integrity and ethics of the education system, in particular, when academics offer students improved marks in exchange for sex. Mazibuko & Umejesi (2015) referred to this type of exchange as transactional sex, whereby women have sex in situations where they might otherwise refrain or have sex with a non-primary partner which was motivated by material gain.

GBV is recognised in South Africa as a profound violation of women’s human rights and as a major barrier to social and economic development (Usdin et al., 2000). However, according to Peacock (2012), gender equality in South Africa must be framed within a human rights agenda and intended to further women’s and men’s full access to and enjoyment of their human rights. The fact that South Africa’s commitments towards the global and regional gender instruments are essentially voluntary and not supported by strict monitoring, enforcement and punitive sanctions poses important policy implications. This undermines the obligations towards gender equality and women’s empowerment at South Africa’s universities.

Culture of violence

Part of the blame for violence against women is an alleged “culture of violence” in South Africa, within which violence is accepted as a way to resolve disputes, even in the post-apartheid era (Bowman, 2003). Tracing the history of colonisation and apartheid is to trace a history of dehumanization and subordination. The violent history of South Africa has manifested a particularly pernicious reality for post-apartheid (Gqola, 2016). At the intersection of racism, poverty and sexism, young black women have withstood the worst of violence and discrimination.

South African scholars emphasise violence as stemming from a desire to exert power and control over women, but this falls under the rubric of a “culture of violence” entrenched in traditional communities. Violence against women is the second leading cause of death in South Africa. The South African government should identify ways to reduce violence against women and injuries as a key goal, and to develop and implement a comprehensive, national, intersectoral, evidence-based action plan (Seedat et al., 2009). However, a policy meant to provide guidelines to be rolled out at police stations in order to assist women when reporting GBV, was never made public or implemented. According Lisa Vetten (cited in Saba, 2017), without credible statistics on GBV and femicide, it is difficult for the public to understand the problem around violence against women. Femicide is the killing of women by a stranger or known person. GBV in South Africa is widespread. In 1999, a woman was killed every six hours in South Africa by her male intimate partner. A decade later, in 2009 the rate of femicide in South Africa stood at one woman killed by her intimate male partner every eight hours (Mazibuko, 2017a). According to Mathews et al. (2004), South Africa has a rate of intimate femicide that exceeds reported rates for other countries.

GBV statistics in South Africa

According to Machisa (2011), during 2008-2010 in the Gauteng Province alone, 15,307 cases of GBV were opened of which 12,093 cases involved females as victims. Thorpe (2013) views violence against women as particularly hard to measure because the police in South Africa do not keep separate statistics on assault cases perpetrated by husbands or boyfriends. He adds that even domestic violence statistics are almost impossible to access because domestic violence is not in itself a crime category, even though, according to the National Instructions 7/1999 relating to the implementation of the Domestic Violence Act 116 of 1998 in police stations, all domestic violence incidents must be recorded in a Domestic Violence register. Bendall’s (2010) analysis is that women in South Africa are predominantly under the control of men and often simply accept their position as the victim. As a result, it is impossible to quantify the full extent of the problem of violence and the statistics tends to underestimate the full extent, as many victims do not come forward. This implies that there may be many unreported cases of violence against women, at universities, private and public sectors, urban townships and in the rural communities. South Africa has to double its efforts to tackle this problem. Regardless, South Africa has committed itself to the NDP 2030 to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking, sexual and other types of exploitation (NDP 2030).

Findings

In recent months of 2017, South African societies seem to have finally awoken to a social ill that has been plaguing the country for years: violence against women. Mazibuko (2017b) referred to this as “pandemic” which has continued unabated, despite of Domestic Violence Act 116 of 1998, everyone in the society is aware of it, and in most cases people witness it and do not voice their disapproval of it. The majority of the victims of femicide were women aged 18-35. South Africa regards this age range (18-35) as the youth.

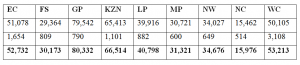

The findings begin with a table drawn from STATS SA DOMESTIC VIOLENCE REPORT 2016/2017. These are the number of cases registered in the nine provinces of South Africa. Eastern Cape (EC), Free State (FS), Gauteng Province (GP), KwaZulu Natal (KZN), Limpopo Province (LP), Mpumalanga Province (MP), North West (NW), Northern Cape (NC), Western Cape (WC). In the second row is the number of protection orders recorded. The third row is the number of contravention orders recorded. Highlighted in the fourth row are the total number of protection orders and contravention orders recorded in 2016/2017.

Based on the above statistics, Gauteng Province has the highest number reported protection orders and Western Cape Province has the highest number of contravention orders. South Africans need to critically evaluate these numbers and ask themselves as to what point do these protection orders and contravention order have instigated femicide in these provinces. Based on these findings South Africa must recognise that violence against women is a serious social evil, which is within South African society. Lebitse (2017) argues that South Africa should enact legislation that focuses on femicide, considering the overwhelming statistics of brutality against young women.

Conclusion

This paper has discussed the concept of gender-based violence from a global perspective and from a South African perspective. GBV statistics show one woman killed by her intimate male partner every eight hours. These statistics on femicide are alarming. Farber (2017) argues that intimate femicide or murder of a female partner and GBV are very common crimes in South Africa. Most critical is the fact that it is impossible to quantify the full extent of the problem of violence against women and the statistics tend to underestimate the full extent, as many victims do not come forward.

Agenda (2063) suggests that all forms of violence and discrimination (sexual, social, economic and political) against women and girls will be eliminated in Africa. However, to live in South Africa is to live in a state of paralysis, a coma of inculcated denial and repression. South Africa has the world’s most progressive constitution, which aims to protect and enshrine the rights of women, yet it is the rape capital of the world.

If South Africa’s universities continue to lack a dedicated policy to combat GBV, women will continue to live in fear and remain at risk. NDP 2030 policy will fail its plan of student retention rate by 90 percent and increase the numbers of students who successfully graduate. South Africa has a duty to intervene proactively to protect women from GBV. Policies, non or governmental organisations and universities are powerful tools for social change and for empowering women.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 7 November 2017

References:

Agenda 2063. African Union Commission Archives.

Bendall, C. (2010), The domestic violence epidemic in South Africa: legal and practical remedies. Women’s Studies, 39(2): 100-118.

Bowman, C. G. (2003), Theories of domestic violence in the African context. Journal of Gender, Social Policy & The Law, 11(2): 847-864.

Campbell, C. (1991), The township family and women’s struggles. Agenda, 6(6): 1-22.

Commission for Gender Equality (2016a), Fighting fire with (out) fire: Assessing the work of police stations in combating violence against women.

Commission for Gender Equality (2016b), Policy Brief: On paper and in practice: The challenges of South Africa’s compliance with global and regional gender instruments.

Farber, T. (2017), Why women kill. Sunday times. 30 July p15.

Gqola, P. D. (2016), South Africa’s nightmare. A Woman’s Journey Essays of Africa, 50-52.

Jewkes, RK & Morrell, R. (2010), Gender and sexuality: emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 13(1): 6.

KPMG (2014), Too Costly to Ignore: The Economic impact of gender-based violence in South Africa. KPMG Human and Social Services: South Africa.

Machisa, M. (2011), South Africa: domestic violence must be included in crime stats. Gender links for equality and justice. Available at: http://www.genderlinks.org.za/article/south-africa-domestic-violence-must-be-included

Mathews, S, Abrahams, N, Martin, LJ, Vetten, L, Van der Merwe, L & Jewkes, R. (2004), Every six hours a woman is killed by her intimate partner: a national study of female homicide in South Africa. MRC Policy Brief 5, 2.

Mazibuko, N. C. & Umejesi I. (2015), Blame it on alcohol: “passing the buck” on domestic violence and addiction. Generos: Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies 4(2):718-738.

Mazibuko, N. C. (2017a), Checkmating the mate: power relations and domestic violence in a South African Township. South African Review of Sociology Journal, 48(2):18-31.

Mazibuko, N. C. (2017b), How to beat women abuse: something must be done and it starts with each of us. Pretoria News, 1 August p8.

McCarry, M. & Donaldson, A. (2017), Gender based violence on UK campus’: intervention, prevention and policy response. European Conference on Domestic Violence: 2017-09-06-2017-09-09, University of Porto.

National Development Plan 2030. Our future make it work. Executive Summary: Policy report.

Lebitse, P. (2017), Femicide needs its own laws. Mail & Guardian, 7 July p29.

Schwitters, A., Swaminathan, M., Serwadda, D., Muyonga, M., Shiraishi, R.W., Benech, I., Mital, S., Bosa, R., Lubwama, G., Hladik, W. (2015), Prevalence of rape and client-initiated gender-based violence among female sex workers: Kampala, Uganda, 2012. AIDS Behavior, (19):68-76.

Walby, S. (1989), Theorising Patriarchy. Sociology, 23(2): 213-234.

Biography:

Dr Nokuthula Caritus Mazibuko is a senior lecturer in the Department of Sociology: University of South Africa. Her research interests include domestic violence, gender-based violence, policy and gender mainstreaming.