Article: The End of Kids Company: Making Sense of Closure

This article examines the reports and findings of reviews carried out into the closure of Kids Company in 2015. Molina argues for further research into the closure of youth organisations in order to better understand how management processes and youth policies can be improved to help ensure quality services are offered to young people.

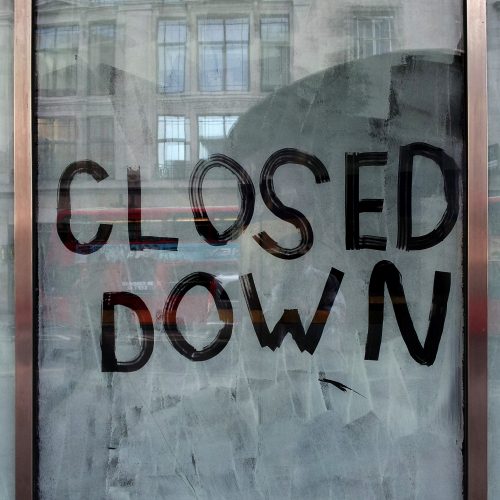

This article explores the closure of Kids Company and outlines the analytic potential of examining organisational closure and collapse. In doing so, I aim to indicate some future lines of inquiry in scholarship focused on the conjunction between youth and policy. I do this by examining one case, the end of Kids Company. Until early August 2015, Kids Company, a UK-based charity founded by a Camila Batmanghelidjh, delivered a range of children and youth-focused interventions in London, Bristol and Liverpool. With a high-profile founder, thousands of service users, endorsements from celebrities and politicians, and tens of millions of pounds in voluntary donations and government grants, Kids Company was, on the face of it, a success story of the provision of support services.

This article principally focuses on events taking place after the summer of 2015, when the future of Kids Company was in doubt, and after the charity had been put into compulsory liquidation. During these months, news reports focused on the financial mismanagement in Kids Company, a general failure of leadership by both managerial staff and members of the executive board, allegations of sexual offences, exploitation, child abuse, and other suggestions of professional misconduct. The article suggests that this case can be used to examine the conjunction between youth and policy, voluntary sector service provision and government inquiries into organisational governance (Berlant 2007).

In one sense, the closure of Kids Company can be analysed as occurring in the face of austerity policies and in a context of governmental reforms to the provision of public services. This could be supported by citing neoliberal orthodoxies about the introduction of market-based competition and other market mechanisms affects the structural provision of youth services. It could support these claims by citing news reports, policy analyses and academic research which have enumerated the closure of youth centres and explored the experience of young people and practitioners who face cuts to the provision of both local authority and voluntary youth services. The article will outline some other considerations that were made relevant to Kids Company’s closure: interrogations about failures in administration, and ‘what next’ for service users. These additional considerations were elaborated in the accounts of former staff and board members, service users and politicians. These accounts suggest other analytic possibilities for examining the demise of Kids Company, as well as future directions for scholarship about youth and policy.

‘You are running an organisation without records’

Following the closure of Kids Company, a number of public inquiries were launched which focused on identifying the causes and consequences. The most notable of these were led by parliamentary bodies and regulators, such as the Public Accounts Committee, the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC), the Charity Commission and National Audit Office. Each of these bodies traced various lines of investigation into the circumstances under which Kids Company had closed, gathered different kinds of evidence, organised the collection of this evidence, interviewed witnesses, presented findings and issued recommendations about lessons to be learnt from this case. Without exhaustively reviewing the scope and findings of each of these inquiries, I will briefly outline one recurrent topic in media accounts and public evidence sessions held at the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC): issues associated with failure to competently administer the organisation.

After the closure of Kids Company, media reports suggested that there were long-standing issues in the management of the organisation. These issues concerned how charitable organisations should normally be administered, through audits for quality assurance, financial management and risk assessments (Travers 2007). These reports involved descriptions of the way that the administration of Kids Company had been problematic. Examples of such accounts were given by people with prior contact with the organisation. In an interview broadcast on BBC’s Newsnight on the 14th of October 2015, Professor John Podmore of The Pilgrim Trust described the reasons behind why his organisation had turned down Kids Company’s grant bids: ‘In 2002 we initially awarded a grant to Kids Company but after requiring and asking for various information to do with the project and the finances we withdrew it. They applied again in 2009 and again on examination of the bookkeeping, the finances, the general financial structure we were sufficiently concerned not to take the bid forward’.

On the following day at PACAC’s evidence session, committee members asked both the founder, Camila Batmanghelidjh, and board member, and Alan Yentob, about such issues. Members followed up with questions about their competence, knowledge and fulfilment of normal leadership responsibilities. Their questions concerned whether proper management had been exercised over Kids Company. Each of these questions involved addressing safeguarding procedures, whether Kids Company was inspected by regulatory agencies such as Ofsted, whether Camila Batmanghelidjh had appropriate professional accreditation and was a member of any professional bodies, how the organisation distributed monies to clients, whether they kept records, shredded records, or shared these records about client groups with local authority social services.

Committee members drew upon testimonies and media accounts to formulate these questions. They cited former staff members’ accounts about a routine practice of handing cash to young people. One member cited a description of this practice: ‘One former employee saying that cash was distributed in little packages to every young person through a small window in reception’ (see also Maitland Hudson 2015). One member referred to this practice as issuing ‘monies, vouchers and similar instruments’. Members asked about the ‘proper financial management’ of this practice. Members asked questions about who at Kids Company had to approve the distribution of these monies, how much money was given out and to whom, on what basis was cash handed out, and what controls were put in place about how much was given to each individual. Members also drew from other witness testimonies which stated that for many of these clients ‘there was not a need for those clients to have any support’. One member asserted that Kids Company ‘were servicing clients where the need did not exist’.

PACAC members repeatedly asked about the regulation of Kids Company. These questions focused on whether Camila Batmanghelidjh had the necessary qualifications to diagnose service users, whether she was a member of any professional body, and which professional bodies she was accountable to. Other questions addressed the inspection regime Kids Company was subject to. Members asked how trustees and board members of a ‘large organisation’ satisfied themselves without being inspected by relevant regulatory bodies, such as the Care Quality Commission or Ofsted: ‘I know of no other large organisation that looks after children in this country that is not regularly inspected’, one member stated.

Another line of questioning concentrated on Kids Company’s client base and the maintenance of records about these clients. Again, members drew upon evidence from former employees: ‘past employees expressed cynicism about the accuracy of the suggestion that the number of clients you had in 2010 was 16,500 and the numbers leapt to 36,000 in the following year’. Another member asked, ‘as an ex-employee of yours told The Times that they were instructed to shred client records after the charity closed. Is this an instruction from you and does it mean that records that would prove that there were 36,000 clients do not now exist?’ Throughout the session, members continued to press for answers to these points: ‘can you give me the number please?’, ‘we will be here all day’, ‘why have you not handed them over?’. One member characterised the situation at Kids Company as ‘you are running an organisation without records’.

Life after Kids Company

Another set of accounts explored what would happen after the closure of Kids Company. These accounts came from young people, former employees, and parents of service users. These accounts focused on the closure of Kids Company in terms of speculating about what would happen next. At the same PACAC evidence session previously discussed, Alan Yentob, former board member, offered one example of an already evident consequence of the closure.

What is the worst that could happen? Remember the riots in 2011, which Camila in fact warned Oliver Letwin about–sorry, let me answer your question, I will. Five days after Kids Company closed, a boy was murdered. If you read the account of that and what was said at the time by those people in that area you will hear what they said about the risks that happened once Kids Company had gone (PACAC 2015)

The committee chair, Bernard Jenkins, intervened and challenged this account, explaining alternate reasoning as to why these ‘incidents occurred’. He said, ‘we have been advised that these incidents occurred because kids no longer had money to pay their drug pushers, and the breakdown in the flow of funds on to the streets has led to that violence – your clients no longer being able to pay for drugs’.

Other accounts described possible consequences for young service users. Whilst interviewed on Channel 5 News, a service user named Brittany described how she felt about the closure. ‘Sad,’ she said, ‘because they’re shutting it down and I won’t have nowhere to go after school’. Her mother described how she felt about the closure of Kids Company and what they had done for service users. ‘Really sad, and the kids they’re gonna miss that a lot because they really help a lot of kids. They take them off the street and they support them. And they have a Christmas party for the kids on Christmas day, where you go with the kids and they get a voucher, they give them hot meals, they really do a lot for the kids’. Brittany’s voluntary mentor explained whether her voluntary work could continue. ‘I’m really sad about it, but I did think it was really impressive, I’m waiting to get some advice from them. They’ve emailed out a statement to their volunteers but I’m not really sure about how to go forward with the mentoring… rather than carrying on by my own I’ll probably try to either contact Brittany’s primary school or something to have a bit more structure to it.’

Researching Closure and Youth Service Provision

By drawing from testimony, evidence and media accounts, this brief article has indicated the analytical potential for focusing on the closure of Kids Company and how its causes and consequences were accounted for. By drawing from secondary and archival sources, scholars interested in youth service provision can explore conjunctions between youth and policy. It offers further possibilities for examination. Using the events surrounding organisational closure could offer new insights into the contemporary conjunction between the voluntary and charity sector, media reportage, youth service providers, government departments and financial governance of youth organisations.

A research programme of this kind could contribute detailed case studies which connect the fields of sociology of youth, youth studies, youth and social work, and studies of the interactions between organisations, bureaucracy and public administrations. The closure of Kids Company, and the reports generated about it, offers a plenitude of empirical materials, not limited to television documentaries, broadcast news interviews, panel discussions on radio and television, newspaper op-eds, blog posts, news reports, evidence sessions at parliamentary committees, committee reports, regulatory body reports, to name a few. These materials can be used to further develop the analytic category of closure. This can be done by examining the practices used to account for the interaction between urban youth, youth work services, regulatory oversight and inspection regimes in the charitable and voluntary sector, the allocation of funding and government grants to charities, and the financial governance of youth services. There is a story to be told about how organisational collapse is made sense of by describing the features of normal, ordinary and competent administration.

Such a programme would benefit from drawing connections between research in youth work, social work, social policy, urban studies, organisation studies, public administration, a sociology of interventions, and interactionist sociology (Eyal 2010). It could build upon the kind of detailed, historical studies of the emergence and decline of counter-cultural youth service movements, and how public concerns over social problems are enacted in programmes and policies (Staller 2006). It would also consider the everyday, inter-organisational and inter-professional practices through which community-based groups provide social services in communities (Marwell 2007). It would provide empirical accounts about how practitioners make sense of contemporary transformations of youth work provision in the context of ‘austerity youth policy’ (Mason 2015), and the varying ways in which practices of account-ability – whether financial, moral, or otherwise – are deployed to make sense of charities and voluntary organisations (Roddy, Strange and Taithe 2015).

By examining the closure of Kids Company and how parliamentarians, former employees and service users made sense of its demise, this article has indicated other potential findings from the closure of Kids Company which extend beyond the overarching neoliberal context. Future scholarship on the effects of neoliberal orthodoxy or reforms to the provision of youth provision should be equipped to detail the practices used to make sense of changes, disruptions and closure of organisations.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 16 March 2018

References:

Camila’s Kids Company: The Inside Story, 2016. Directed by Lynne Alleway. UK: Century Films for BBC.

‘Kids Company closure: What went wrong?’. BBC News, 1 February 2017: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-33788415

‘Single mother explains how Kids Company helped her’, Channel 5 News. 7 August 2015. [Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PITXYz-PJuI

Berlant, L., 2007. ‘On the case’. Critical Inquiry33(4): 663-672.

Cook, C., 2015. ‘The fall of Kids Company’. BBC News, 12 November.

Eyal, G. and Buchholz, L., 2010. ‘From the Sociology of Intellectuals to the Sociology of Interventions’. Annual Review of Sociology36: 117-137.

Goslett, M. 2015. ‘The trouble with Kids Company’. The Spectator, 14 February.

Maitlin Hudson, G, 2015. ‘We need to talk about Kids Company’. OSCA blog, 11 February 2015. [Available: http://osca.co/2015/02/need-talk-kids-company/

Marwell, N.P., 2007. Bargaining for Brooklyn: Community Organizations in the Entrepreneurial City. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

Mason, W., 2015. ‘Austerity youth policy: exploring the distinctions between youth work in principle and youth work in practice’. Youth & Policy114: 55-74.

National Audit Office, 2015. Investigation: The government’s funding of Kids Company.

Public Accounts Committee, 2015a. Report: The Government’s funding of Kids Company. Eighth Report of Session 2015-16. HC 504.

Public Accounts Committee, 2015b. ‘Written evidence: Department for Education’. Date published, 9 December 2015.

Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee, 2015. Whitehall’s relationship with Kids Company – Oral evidence. HC 433.

Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee, 2016. 5th Report – The collapse of Kids Company: lessons for charity trustees, professional firms, the Charity Commission, and Whitehall. HC 963.

Roddy, S., Strange, J.M., and Taithe, B., 2015. ‘Humanitarian accountability, bureaucracy, and self-regulation: the view from the archive’. Disasters 39 (s2): 188-203.

Shaw, J., 2015. ‘Guardian Letters: A balanced view of Kids Company’. The Guardian. 10 July.

Staller, K.M., 2006. Runaways: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped Today’s Practices and Policies. Columbia University Press, New York.

Travers, M., 2007. The New Bureaucracy: Quality Assurance and Its Critics. Policy Press, Bristol.

Walters, S., Goslett, M, and Vraven, N., 2015. ‘Camila’s own private swimming pool… in luxury mansion paid for by Kids Company: Children who used £5,000-a-month home were banned from the pool – in a house lived in by aide she “doesn’t know from Adam”’. Daily Mail, 15 August.

Biography:

Julian Molina is an ESRC-funded doctoral student in the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick. He is completing his doctoral research on the organisation of education, employment and training interventions with young people. He has conducted ethnographic fieldwork with employment related service professionals, NEET tracking teams, youth workers and lobbying groups.