Home > Articles > Transcending Resilience

Article: Transcending Resilience

Author: Sandra Vacciana | Tags: co-production, minoritised communities, peer research, race, racism, resilience, social justice, young people, youth work

In this article, Sandra Vacciana discusses findings from a peer research project that critically explored the role of resilience in supporting the wellbeing of young people from minoritised communities, with racialised identities. The findings of the study make a compelling case for the youth sector to expand its understanding of the term resilience. The article outlines the experiences of young people who have had to become adept at rising in the face of adversity and questions the concept of resilience when understood uncritically and disconnected from social structures that constrain young people.

Setting the Context

In February 2021, a group of twelve peer researchers and staff from the Regional Youth Policy Unit at Partnership for Young London (PYL) embarked on an inquiry. The goal was to discern what strategies support young people from Black, Asian, Traveller, LGBTQ+, and other minoritised and ‘unseen’ groups, to build the personal skills that support them through turbulent times. Central to the research was the recurring question:

What else should we be doing to address the social conditions which undermine the life chances of young people with minoritised and racialised identities, triggering their need for sustained resilience?

The initiative was part of a larger six-month programme of events and training funded by The National Lottery Community Fund.

Our work drew on recent reports including ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Young People and the Youth Sector’ published by UK Youth (2020a) and ‘Disparities in the Risks and Outcomes of COVID-19’ published by Public Health England (2020). These reports highlighted the disproportionate effects of the pandemic on people from minoritised communities.

These injustices were compounded for young minoritised people through additional pressures they experienced during lockdown. These pressures included increased racial profiling by the police, who stopped and searched more than 22,000 young Black men in London during the first lockdown alone (Grierson, 2020). Other additional pressures included loss of education, soaring unemployment and reduced support networks (Fleming, 2021; UK Youth, 2021). The inequalities compounded by the pandemic were further exacerbated by systemic racism, brought to public attention through social movements like Black Lives Matter, following the murder of George Floyd (Dodd, 2020). These combined factors had a corrosive impact on the emotional wellbeing of minoritised young people (UK Youth 2020b).

Methodology, Process and Practice

Our methodology involved each participant in the study adopting the dual role of being both ‘the researcher’ and ‘the researched’. The core intention was to create an ethos where sharing and owning aspects of our own stories and learning from the stories of others were held as high values. We wanted to create a research opportunity that explored subtleties amongst and between our lives, giving a richer, more complete sense of the impact caused by being compelled to learn the skills of resilience as a means of survival.

This work was co-produced to democratise the research process. We centred the voices of women, people with racialised identities from minoritised communities and people from LGBTQ+ communities, in recognition that research and policy development are primarily conducted by ‘an Anglo- Saxon patriarchy and should be person centred and egalitarian’ (Hart et al, 2016, p.6). Additionally, we applied Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989) framework of intersectionality to understand how aspects of our identities overlap and reinforce oppression.

Reflective practice was also a tenet of our methodology. The tutors, who were of African, Caribbean, and white Irish descent, remained fully cognisant of the power dynamics underlying racial identities in a group where we were prioritising the stories of people from racialised and minoritised backgrounds. Colette, who is white and of Irish ancestry, observed that:

To do this project justice, tutors had to reckon with the underlying ideology that ‘whiteness’ is the norm from which everything else is measured. (Colette Ferns, Academic Supervisor)

It was also essential to investigate the disenfranchisement that comes from homogenising the identities of ethnic groups and the inherent discrimination experienced by being ‘…a minority within a minority’ (Chelsea McDonagh, Tutor).

Self-reflection supported the dexterity to notice more nuanced observations and balance a level of objectivity with recognising moments to introduce views from one’s own lived experience to the process. One example of ‘noticing’ was respecting the modes of communication members of the group used to share their ideas.

The project meetings were conducted via video call and the use of cameras dropped off quite rapidly after the initial sessions. Despite this, the connectivity between group members grew from one meeting to the next, suggesting a correlation between the two. Having our cameras off tested the assumption that we need to be seen to fully engage. The black boxes on our screens provided a practical and protective shield, offering a break from the pressures and constraints of staring into and being seen through a device. It signalled a green light to those needing to multi-task, share their physical space with others, or just to take a beat or two to breathe.

There was absolute fascination when, in the penultimate session, members of the group took up the invitation to turn their cameras on. The faces that filled our screens marked our arrival at a project milestone. A uniting ‘I am Spartacus’ moment, commented Arden, and a collective witnessing of what had been achieved.

Design, Delivery and Analysis

Focus groups and one-to-one interviews were used for generating qualitative data. Members of the group learned how to develop research questions, facilitate sessions and analyse data. Once the training was over, the larger group was divided into two sets. Each sub-group produced research questions, then took it in turns to deliver a focus group to one another. One-to-one interviews were also conducted. Once the answers from the focus groups and interviews were transcribed, the peer researchers learned how to code data and identify themes in participants’ responses. After a deeper dive into the information gathered, members of the group contributed to writing up the findings of the research and are quoted and credited extensively in the final report (Vacciana, 2021).

What Emerged

The project outcomes reinforced some of what we already know. Whether inner strength was grounded in an organised religion, or feeling an interconnectedness with nature or art, all peer trainers expressed a sense of comfort and reassurance in the appreciation of a ‘higher power’ or something ethereal, outside of themselves. Having a support network of (found) family members and friends as well as being able to assert self-agency were also crucial to navigating tough times.[1] However, this work also highlighted how human rights were considered ‘good fortune’ by some. One such example was in relation to boundaries.

There is a paradox when speaking of resilience as it is traditionally understood. To have resilience you need to identify and enforce boundaries. Yet if one is part of a minoritised and/or racialised community one is less likely to have the ‘advantage’ or the circumstances to do either. What is assumed in the Western narrative to be the keystone of self-actualisation and fully expressed personhood, is revealed to be a ‘luxury’. (Arden Fitzroy, Peer Researcher)

The data also unearthed less well documented themes that broadened understandings of how young people from racialised communities cultivate inner strength. These included topics such as ‘Allyship’, ‘Liminal Space’, and the ‘Role of Older Sisters’ in the lives of young Black and Asian women.

Social Justice and Allyship

Advocating for greater internal resolve without also looking to the external systemic pressures, steeped in a colonial past, that necessitate resilience only increases oppression. This understanding crystalised how social constructs such as race, gender and ableism impact young people already facing inherent social inequalities because of their age, as observed by Nadar.

Advising us to be resilient without also looking at how our circumstances could be improved through extensive developments to social policies, is equivalent to telling us to just ‘pull ourselves together’ and endure. (Nadar Abdi, Peer Researcher)

Anti-oppressive behaviours must be practised and will take different forms depending on one’s sphere of influence. Dexter, a young white man from Southeast London and member of the group, shared:

It’s important to realise how much unlearning, relearning, and rewiring must be done by white people when committing to anti-racist (and anti-oppressive) practice. Living in a white world, catering for white people, can swallow you up and blind you to your privileges and advantages. (Dexter Dare, Peer Researcher)

Ancestral Ties and ‘The Strong Black Woman’

There is very little documented about the jeopardy that young Black and Asian women adopt in their roles as older sisters, to create better outcomes for themselves and pave the way for younger siblings. The ideology of ‘The Strong Black Woman’ is purposeful and grounded in misogynoir.[2]

I feel not a lot of people talk about older sisters and daughters. They really do go through a lot and that does influence younger siblings, especially for me…I don’t mind stepping out of my comfort zone knowing stuff can happen – like…bad things. Anonymous Peer Researcher 1)

There’s a lot I don’t tend to share…I make sure they don’t see that I struggle. If I have to – I will break barriers for them to walk more smoothly. (Anonymous Peer Researcher 2)

Young Black and Asian women withstand pain to break glass ceilings. The peer researchers shared examples of how their resilience was reinforced by witnessing older sisters ‘being the first’ to go to university, reject marriage and starting a family before completing their education, or generally learning to say ‘no’. Their toughness was costly; defying patriarchs in pursuit of equality often compromised emotional health.

An intervention is required to stem Gen Z, and the young women who follow, from inheriting the toxic myth of ‘The Strong Black Woman’, which strips their humanity by pathologising their strength.[3] This was another key finding of the research.

Liminal Spaces and Young People from Minoritised Communities

There was a shared knowing amongst group members that came from their experiences of being positioned as outsiders that was collectively understood but not always spoken. The experience of resilience that peer trainers described was a liminal space between their internal and external worlds, where ethereal features were cited as also being central to boosting their core strength.

This liminal frequency traversed past, present and future, giving access to the grit and vision of ancestors, who gifted peer researchers with the will to rise again. So, the concept of time was also an important factor within this work. There was a routinised mobilising of strength acquired from knowing about the resiliency of their ancestors, rooted in the past, that empowered group members to thrive in the ‘present tense’ (Baraitser, 2017, p.116). Exploring the sub-conscious and unconscious factors that resource young people through challenging times could provide a wealth of new knowledge for future (decolonised) models of resilience.

A Call to Action Going Forward

Placing an emphasis on gathering stories as opposed to ‘collecting data’ enriched the process of this research by humanising the themes and making them more relatable. The project utilised an alternative to orthodox research conventions by training participants to become co-producers; inviting everyone to share the direction and ownership of the work. As co-producers, the participants were all ‘holders of knowledge’, which allowed tutors to build on assets and defer to them as ‘Experts by Experience’.[4]

Remaining open throughout the project enabled us all to constructively challenge the original hypothesis and be open to different perceptions of resilience. Understanding how we uphold social structures within the youth sector and wider community that prompt the need for young people to maintain ongoing resilience, is the heart of the learning from this work.

Often the term [resilience] is used to distract from structural changes that are desperately needed and, instead, places emphasis and responsibility onto those being oppressed. It is undeserved suffering repackaged as a pat on the back – a congratulations for an emotional skill they should never have had to develop. (Chelsea McDonagh, Tutor)

It is time for a radical shift in developing youth policies. Adopting a transdisciplinary approach will allow us to ‘borrow’ ideas across disciplines that assist the application of new praxis. The contributions of young women, people from LGBTQ+ communities, those from Black, Asian, and Traveller communities, and other ‘unseen’ and/or minoritised demographic groups, should be integral to strategies addressing inequalities going forward. This will support the process of understanding resilience as a collective endeavour to dismantle social structures of oppression – rather than a personal quest to ‘keep on, keeping on’.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 31 August 2022

Footnotes:

[1] ‘Found Family’ was a term expressed to describe finding kinship within LGBTQ+ communities. It could also refer to other networks made up of relationships people are not born into.

[2] The term misogynoir describes the combined oppression Black women face because of their gender and racialised identities. It was introduced by Moya Bailey in 2010. See Mwanza (2018) and MIT (2021) for a summary and definition.

[3] See Patricia Hill-Collins (2000) Black Feminist Thought and the chapter entitled ‘Mammies, Matriarchs and Other Controlling Images’ for further analysis on the construction of Black women’s identities.

[4] See Baljeet Sandhu (2017) for a review of working with people who utilise their lived experience to create social change.

Acknowledgements:

The team involved in the peer research project were as follows:

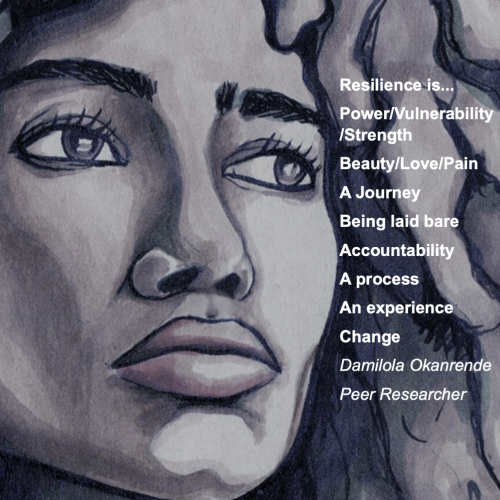

Peer Researchers: Nadar Abdi, Carlotta Naima Adams, Dexter Dare, Antonio Ferreira, Arden Fitzroy, JazzmineJada George, Salem Habtom, Muntaha Hussain, Humayra Islam, Comfort Nwabia, Damilola Okanrende, Arif Hoque Shah.

Tutors: Sara Ahmed, Chelsea McDonagh, Sandra Vacciana, Matthew Walsham.

Academic Supervision: Colette Ferns.

Artwork: Drew Sinclair

References:

Baraitser, L. (2017). Enduring Time, London: Bloomsbury.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. University of Chicago Law School, Article 8, pp.139–168. Available: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

Dodd, V. (2020). Black People Nine Times More Likely to Face Stop and Search than White People. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/oct/27/black-people-nine-times-more-likely-to-face-stop-and-search-than-white-people.

Fleming, S. (2021). World Economic Forum. The Pandemic has Damaged Youth Employment: Here’s How We Can Help. Available: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/pandemic-damaged-youth-employment/.

Grierson, J. (2020). Met Carried Out 22,000 Searches on Young Black Men During Lockdown. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2020/jul/08/one-in-10-of-londons-young-black-males-stopped-by-police-in-may.

Hart, A., Gagnon, E., Eryigit-Madzwamuse, S., Cameron, J., Aranda, K., Rathbone, A., & Heaver, B. (2016). Uniting Resilience Research and Practice With an Inequalities Approach. SAGE Open. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016682477.

Hill-Collins, P. (2000). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. New York, USA: Routledge.

MIT (2021). 3 Questions: Moya Bailey on the Intersection of Racism and Sexism.

Available: https://news.mit.edu/2021/3-questions-moya-bailey-intersection-racism-sexism-0111.

Mwanza, C. (2018). Feminist Facts: What is Misogynoir? Available: https://medium.com/verve-up/feminist-facts-what-is-misogynoir-5392c29d6aab.

Public Health England. (2020). Disparities in the Risks and Outcomes from COVID-19. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf.

Sandhu, B. (2017). The Value of Lived Experience in Social Change: The Need for Leadership and Organisation Development in the Social Sector. Available: http://thelivedexperience.org/report/.

UK Youth (2020a). The Impact of COVID-19 on Young People and the Youth Sector.

Available: https://www.ukyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/UK-Youth-Covid-19-Impact-Report-.pdf.

UK Youth. (2020b). #YoungAndBlackCampaign. Available: https://www.ukyouth.org/what-we-do/youngandblack/.

UK Youth. (2021). Young People from Racialised Communities Reimagining Mental Health Support. Available: https://www.ukyouth.org/2021/09/young-people-from-racialised-communities-re-imagining-mental-health-support/.

Vacciana, S. (2021). Unapologetically Me: Transcending Resilience. A report exploring the role of resilience in supporting the well-being of young people with racialised identities, from minoritised communities. Available: https://3532bf5a-d879-4481-8c8f-127da8c44deb.usrfiles.com/ugd/3532bf_ea58afe4cc6f4edd87c1e756a7c486c1.pdf

Biography:

Sandra Vacciana joined Partnership for Young London in 2015. She has been working in the informal education sector since the 1980s, initially in Theatre-in-Education then making a transition to youth work. Sandra has remained interested in using the arts as a powerful resource to explore social issues. Over the last 7 years she has been developing the use of creative methodologies in her practice, as part of the process of delivering participatory research. Sandra is the National Lead for Authoring Our Own Stories – a youth recovery initiative, investigating the influence of young people’s civic identities on access to youth services.